In Hollywood, where everything from the latest Scorsese to Piranha 3-D is marketed as “a major motion picture,” you might think that there’s no such thing as a minor one. But the two-reel comedies of the Three Stooges might just qualify. Nobody involved in their production — not the stars, not the producers — thought they were crafting anything for posterity. In an era when “going to the movies” was an all-day affair, these 18-minute mini-movies were never meant to be more than a time-filler, inherently disposable.

In Hollywood, where everything from the latest Scorsese to Piranha 3-D is marketed as “a major motion picture,” you might think that there’s no such thing as a minor one. But the two-reel comedies of the Three Stooges might just qualify. Nobody involved in their production — not the stars, not the producers — thought they were crafting anything for posterity. In an era when “going to the movies” was an all-day affair, these 18-minute mini-movies were never meant to be more than a time-filler, inherently disposable.

A funny thing happened on the way to that presumed disposability, though. The afterlife of TV syndication made the Stooges iconic for generations of young fans even as more “major” talents faded into film history; Buster Keaton’s stock is as high as ever among the cognoscenti, but it’s Moe, Larry and Curly that your nearest ten year-old will recognize on sight.

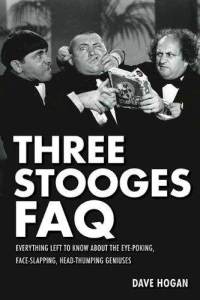

David J. Hogan combines the perspectives of the film historian and the ten year-old fan in his exhaustive new reference, The Three Stooges FAQ. (A side note on the title: none of Hal Leonard’s new “FAQ” series of books is actually an FAQ — i.e., a list of Frequently Asked Questions and answers. The name falls into the great tradition of out-of-date Internet references (mis)calculated to appeal to The Kids These Days; we should be grateful, I suppose, that they didn’t call it The Three Stooges Ate My Balls.) He has the latter’s appreciation for a vigorous eye-gouge, coupled with the former’s deep knowledge of the intricacies and obscurities of his topic.

And obscurities there are in plenty. Between 1934 and 1959, the short-subjects division at Columbia Pictures cranked out hundreds of hours’ worth of two-reelers. Shot on the cheap and cast with no-name contract players, most of this material — including a series of Shemp Howard solo shorts — has been out of general circulation for years, viewable only on privately-owned 16mm reels and bootleg VHS. These films, whatever their merits, may never see the light of day again; and even the mighty Internet Movie Database is of little help in tracking their creators.

With the work of the Three Stooges, the situation is made more complex yet by the two-reel unit’s practice of recycling previously-shot footage into new shorts, padded out with pick-ups sometimes filmed years after the fact. (1957’s Guns a Poppin’, for instance, lifts a number of sequences from Idiots Deluxe, released twelve years earlier.) It presents a confounding obstacle to any film historian. But Hogan rises to the challenge, breezily unpacking the tangled shooting and distribution histories of every Three Stooges short, and provides brief but vividly-written appreciations of each, along with profiles of key writers, directors, and supporting players from throughout the franchise’s history.

The Three Stooges FAQ employs an innovative structure; rather than tackle the boys’ career chronologically, Hogan identifies thirteen primary themes in the shorts — sexual politics, Word War II, the American Frontier, class warfare, the justice system, and so forth — and uses them as a framework to examine, one by one, the 190 films constituting the oeuvre of Howard, Fine, Howard And Sometimes Besser. (This book only concerns itself with the Columbia shorts, disregarding the later TV appearances, cartoon shows, or the feature films with Joe DeRita.)

Comedy, of course, has a way of laying bare the prejudices and mores of its time. While the sociological analysis in The Three Stooges FAQ never gets too heavy (and really, this is Moe, Larry and Curly we’re talking about here; how heavy could it get?), Hogan, to his credit, never excuses or shies away from the occasional ugly aspects of the boys’ legacy: the occasional lapses into misogyny, the xenophobia of the wartime shorts, and especially the pervasive ethnic stereotyping. But he presents evidence (convincing, I think) that the Stooges can be seen as an unexpected force for progressivism, playing against the caricatures. The shorts often evoke the old images purely to subvert them. In a characteristic gag from 1953’s Tricky Dicks, an Italian organ-grinder is introduced as Antonio Zucchini Salami Gorgonzola de Pizza — then proceeds to speak the King’s English with the cut-glass tones of an Oxford don. The laugh (and it is a funny bit) comes from floating the familiar stereotype, and then shooting it down.

[youtube id=”-Z_SolJS1yM” width=”600″ height=”350″]The Stooges’ grandest subversion, alas, never came to be. After Shemp’s untimely death, Moe Howard and Larry Fine lobbied for African-American comic actor Mantan Moreland to come aboard as third Stooge. Moreland was enthusiastic, but Columbia executives scotched the idea. It remains an intriguing might-have-been. The execution could have been audaciously funny, or disastrously offensive — Moreland, though massively popular in his time, made his name by specializing in the kind of bug-eyed, shuffling servant parts that were denounced by later generations of black performers. We will never know how it might have played out; but the sheer boldness of the proposal suggests that the Stooges were not bound by conventional thinking about race.

[youtube id=”dULPXyiVU14″ width=”600″ height=”350″]That being said, there are some squicky passages in The Three Stooges FAQ — and they come straight from David J. Hogan. His appreciation of the performers, especially the starlets, borders on fetishization, and… well, look at this passage about supporting actress Connie Cezan:

[F]unny, saucy, and — partly through no real fault of her own — faintly disreputable, Cezan was pretty in an aggressively sensual way; her wide-set eyes are enormous, and her mouth looks as if it were designed according to a template associated with the erotic arts.

CONNIE SAYS: Yeah say what now?

And the book is full of passages just like that — tossed-off paragraphs praising the loveliness and allure of the minor actresses, in tones that vary from fond to rhapsodic to downright creepy. Mr. Hogan’s dedication to film preservation is admirable, and his determination to give some recognition to these unjustly-neglected performers — never stars, but professionals, working actresses — is both laudable and long overdue. But sometimes, a healthy growing boy needs to get out of the screening room once in a while and meet some girls his own age. I’m just sayin’.

Comments