”Look, I really love you very much and I’d like to be with you, but let’s fuck on tape.”

”Look, I really love you very much and I’d like to be with you, but let’s fuck on tape.”

— Paul Rothchild, producer, to Janis Joplin (quoted by Bruce Botnick)

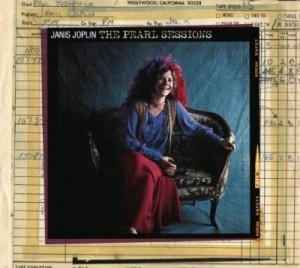

Pearl, the album that became Janis Joplin’s swan song, was at the time of its recording simply the next step in the progression of an artist who often struggled to find the appropriate collaborators with which to exercise her gifts. As documented in the liner notes for The Pearl Sessions, Columbia/Legacy’s new two-disk retrospective of the album, Joplin found the most supportive team she was ever to work with in producer Paul Rothchild and the Full Tilt Boogie Band, her hand-picked ensemble with whom she had road-tested many songs that would end up on the album. The resulting record is the best of Joplin’s short career, and far and away the most successful, riding the number one spot for nine weeks in 1971.

The Pearl Sessions consists of the album proper (along with mono mixes of the singles) and a second disk of outtakes and studio chatter. I won’t go into the original LP much except to say that it hasn’t undergone any remixing or remastering but still sounds great: Full Tilt Boogie played with just right mix of fire and precision, and Paul Rothchild did an excellent job of getting them and Joplin onto tape. As the most commercially and artistically successful album of rock’s pioneering female star, Pearl fully deserves a detailed look. That is where the second disk, featuring many (though not all) never-before-released tracks, comes in.

It should first be noted that anyone looking for a comprehensive account of the album’s making won’t find it — this is a general-interest release, not The SMiLE Sessions. For instance, we’re told that some songs were recorded live with Janis on vocals and others as instrumental tracks for her to overdub later. Why the mixed approach? We don’t know how many takes were recorded for each track (two different performances of ”Get It While You Can,” recorded a month apart, are both listed as ”take 3″) or how many extra tracks went unused. These questions are important for two reasons: for one, they reveal how much influence Joplin, neither a prolific composer nor arranger, had over the final shape of the material. As for the second reason, let’s be frank: Joplin died of an overdose before the sessions were complete. I understand the label’s and Joplin’s family’s reasons for not dwelling on this tragedy, but any real understanding of this album has to squarely address it. How much of Pearl was what Joplin envisioned, and how much of it was what Rothchild was able to piece together? The answers to all these questions are likely out there somewhere — I frankly admit I am no expert on Joplin’s life — but wherever they are, they’re not contained in this set.

Judging by the material that is presented here, Joplin’s composition ”Move Over” seems to have taken the most effort to get right, with Janis and the band alternately fussing over the tempo, the rhythm accompaniment and John Till’s guitar lines. The easiest, by contrast, may well have been ”Me and Bobby McGee,” a performance that by itself justifies almost every word of praise ever spoken about Janis Joplin. The one alternate take included here is too similar to the final master to be really interesting, suggesting that Joplin, Rothchild and the band were of remarkably similar minds on it from the get-go. That impression is confirmed by the inclusion of a solo demo performance by Joplin, recorded in the studio by Rothchild. The song is already complete: Joplin’s sense of pace and dynamics, her emotional journey through the song, are exactly as they would appear on the full-band version. I would have enjoyed a little fly-on-the-wall peek at the players working out the arrangement, but as far as understanding how the song came to be, it’s plainly not necessary.

Other highlights of the second disk are a longer version of ”Cry Baby,” in which Joplin takes advantage of an extended spoken middle to tear a new asshole into a boyfriend who dumped her, and a mournful instrumental recorded by the band after Joplin’s death, and named for her: ”Pearl.” There are no alternate takes of one my favorites from the album, ”Half Moon,” presumably because it was cut by the band without Joplin (we are thrown a live performance of the song in consolation), nor of the Bobby Womack-penned ”Trust Me.” There are five ”Overheard in the Studio” tracks of Joplin bantering with producer and band: she comes across as fully in charge, even brusque (”Do it right and don’t miss that fucking change!” she snaps before a take), but also bubbling with good humor, cracking herself up during the aforementioned ”Cry Baby.”

While I’m enough of a Joplin fan to have wanted more from The Pearl Sessions — deeper liner notes, more extensive outtakes — it remains a worthwhile peek into the making of a bona fide classic, and a testament to the artistry of a woman whose tumultuous life often obscures her very real, and justifiably enduring, achievements.

Comments