There was a central theme to the work of artist John Mark Heard, and it wasn’t the one most people expected. Sure, he was a part of the CCM community, not only as a performer but an in-demand producer, but that was only a portion of his story. The people with whom he worked over the years, up to his sudden death in 1992, knew him to be a meticulous wordsmith, a consummate musician, and wise enough to keep either skill from ruining a good song. That sense of knowing when to put away fussiness and perfectionism was not lost on the likes of T Bone Burnett, Bruce Cockburn, Victoria Williams, Buddy & Julie Miller, Sam Phillips, and so many others. When the CCM labels shunned Bill Mallonee’s Vigilantes of Love because of his frank and (in this arena) shocking language, Heard championed him, to my knowledge never advising him to change a thing. The central theme of Mark Heard’s music was an exhortation to keep the heart prepared for the greatness to come, but also celebrate what’s here right now, no matter how tattered it might appear.

There was a central theme to the work of artist John Mark Heard, and it wasn’t the one most people expected. Sure, he was a part of the CCM community, not only as a performer but an in-demand producer, but that was only a portion of his story. The people with whom he worked over the years, up to his sudden death in 1992, knew him to be a meticulous wordsmith, a consummate musician, and wise enough to keep either skill from ruining a good song. That sense of knowing when to put away fussiness and perfectionism was not lost on the likes of T Bone Burnett, Bruce Cockburn, Victoria Williams, Buddy & Julie Miller, Sam Phillips, and so many others. When the CCM labels shunned Bill Mallonee’s Vigilantes of Love because of his frank and (in this arena) shocking language, Heard championed him, to my knowledge never advising him to change a thing. The central theme of Mark Heard’s music was an exhortation to keep the heart prepared for the greatness to come, but also celebrate what’s here right now, no matter how tattered it might appear.

And so it is that I’m presenting this under the Dw. Dunphy On… banner versus an honest-to-goodness Popdose Guide, mainly because there’s so much of Heard’s work that cannot be accessed legally, so much more that can but is currently not in the proper hands, and my ability to provide a truly complete retrospective is hampered. I could have tossed out the attempt and moved on to another artist, or I could follow the man’s lead and celebrate that which is available, all in hopes that a more thorough version can one day exist. So, without further delay, here is the music of Mark Heard, as best as I know it.

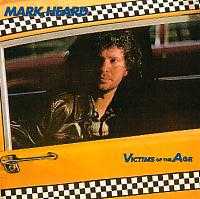

In 1982, Heard’s Victims of the Age

In 1982, Heard’s Victims of the Age![]() arrived and marked several changes. Prior to the album, his themes were very Christian-based, where the new material had a more universal approach. The sound was modern for the time, as was the prior year’s Stop the Dominoes

arrived and marked several changes. Prior to the album, his themes were very Christian-based, where the new material had a more universal approach. The sound was modern for the time, as was the prior year’s Stop the Dominoes![]() , but before those Heard was recognized more as a roots-folk performer. This particular album focused on the dehumanizing effect of modern society, a theme expressed no stronger than on the one-two combination of “City Life Won’t Let Up” and “Faces in Cabs“. The new wave/rock style found on the album would take a break for the next two releases, Eye of the Storm

, but before those Heard was recognized more as a roots-folk performer. This particular album focused on the dehumanizing effect of modern society, a theme expressed no stronger than on the one-two combination of “City Life Won’t Let Up” and “Faces in Cabs“. The new wave/rock style found on the album would take a break for the next two releases, Eye of the Storm![]() (1983) and Ashes and Light

(1983) and Ashes and Light![]() (1984), as he sought to strengthen his preferred acoustic-based sound, an approach that would pay dividends on later albums.

(1984), as he sought to strengthen his preferred acoustic-based sound, an approach that would pay dividends on later albums.

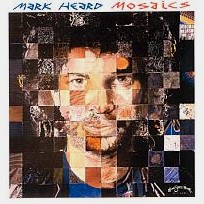

Heard’s return to rock on 1985’s Mosaics

Heard’s return to rock on 1985’s Mosaics![]() melds the two musical personalities into a rootsy John Mellencamp-like flavor, allowing the acoustics a degree of bigness without being hampered by electronics. This is a constant thread in his musical output, stepping in and out of stylistic puddles, sometimes blending them for effect. Speaking of blending, Mosaics can be considered a nexus point for T-Bone Burnett and Sam Phillips, as Heard covers the Truth Decay

melds the two musical personalities into a rootsy John Mellencamp-like flavor, allowing the acoustics a degree of bigness without being hampered by electronics. This is a constant thread in his musical output, stepping in and out of stylistic puddles, sometimes blending them for effect. Speaking of blending, Mosaics can be considered a nexus point for T-Bone Burnett and Sam Phillips, as Heard covers the Truth Decay![]() track “The Power of Love” — One track later, Phillips sings backup on “It Will Not Be Like This Forever“. Two years later, Phillips would release her career-redefining The Turning

track “The Power of Love” — One track later, Phillips sings backup on “It Will Not Be Like This Forever“. Two years later, Phillips would release her career-redefining The Turning![]() , produced by Burnett, but that’s a story for another day.

, produced by Burnett, but that’s a story for another day.

Tonio K. started a record label called What?, a joint venture between CCM conglomerate Word and A&M Records. It was not only a home for his releases but for peculiar artists like Dave Perkins and the one-man band Ideola, Mark Heard’s drift back into the angular, synth-driven new wave sound. (For the sake of fairness, while Heard did most of the work on the album, The Choir’s Steve Hindalong provided percussion, dulling Ideola’s one-man band tag a bit.) 1987’s Tribal Opera, while unique and daring, did not do particularly well on either side of the distribution deal, exacerbating the curse Heard had been pegged with almost his entire career: being too secular for the saints, too religious for the radio. It didn’t help that a couple of the songs simply didn’t work very well. Even so, a few tunes that would later be considered Heard classics were first heard here, including “Watching the Ship Go Down” and “How to Grow Up Big and Strong“.

Tonio K. started a record label called What?, a joint venture between CCM conglomerate Word and A&M Records. It was not only a home for his releases but for peculiar artists like Dave Perkins and the one-man band Ideola, Mark Heard’s drift back into the angular, synth-driven new wave sound. (For the sake of fairness, while Heard did most of the work on the album, The Choir’s Steve Hindalong provided percussion, dulling Ideola’s one-man band tag a bit.) 1987’s Tribal Opera, while unique and daring, did not do particularly well on either side of the distribution deal, exacerbating the curse Heard had been pegged with almost his entire career: being too secular for the saints, too religious for the radio. It didn’t help that a couple of the songs simply didn’t work very well. Even so, a few tunes that would later be considered Heard classics were first heard here, including “Watching the Ship Go Down” and “How to Grow Up Big and Strong“.

Heard fell off the radar for the next few years, resurfacing in 1990 with what would become the first of a crowning trilogy of work. Gone was the Ideola persona and any need to pursue anything he was not particularly interested in, including fitting into others’ marketing strategies. Dry Bones Dance

Heard fell off the radar for the next few years, resurfacing in 1990 with what would become the first of a crowning trilogy of work. Gone was the Ideola persona and any need to pursue anything he was not particularly interested in, including fitting into others’ marketing strategies. Dry Bones Dance![]() revels in almost every facet of what we consider Americana; the lyrics are rendered as these little vignettes, sometimes full of faceted detail, sometimes so conversational it seems like deja vu, like something you’ve already said presented in song. “Everything Is Alright” is an ode to love in the face of a world that has little knowledge of such things, the title track is a rip-roaring resurrection stomp, and “House of Broken Dreams” a lament for things unrealized. During this time period, CCM was obsessed with “getting the kids” with failed attempts to speak the lingo of the day, trying to emulate their worldly counterparts. With Dry Bones Dance, Mark Heard arrived with textured, wonderfully realized music for adults, and a whole legion of new fans suddenly had to explore the rest of his catalog.

revels in almost every facet of what we consider Americana; the lyrics are rendered as these little vignettes, sometimes full of faceted detail, sometimes so conversational it seems like deja vu, like something you’ve already said presented in song. “Everything Is Alright” is an ode to love in the face of a world that has little knowledge of such things, the title track is a rip-roaring resurrection stomp, and “House of Broken Dreams” a lament for things unrealized. During this time period, CCM was obsessed with “getting the kids” with failed attempts to speak the lingo of the day, trying to emulate their worldly counterparts. With Dry Bones Dance, Mark Heard arrived with textured, wonderfully realized music for adults, and a whole legion of new fans suddenly had to explore the rest of his catalog.

Because of the on-off nature of Heard’s prior output, no one had any reason to expect something like another Dry Bones Dance, but Second Hand

Because of the on-off nature of Heard’s prior output, no one had any reason to expect something like another Dry Bones Dance, but Second Hand![]() (1991) proved to be even warmer and more intimate. The title is derived from the track that would come to be his signature tune, the paean to wonderful love in the midst of banal reality “Nod Over Coffee“. In keeping with his newfound desire to follow his muse, he includes a cover of the Beatles’ “I’m Looking Through You,” which in itself is a somewhat rude dressing-down sort of song. Even more jarring, but no less profound, is his original “What Kind of Friend.” The album represented something like a call to liberation within the CCM realm as artists started seeing how far one could go if they went there in the spirit of truth. Most of them paid dearly for it, while those that continued to play it safe reaped the benefits of hanging tight with the game plan. The secular world really had no clue these things were going on and, honestly, didn’t much concern themselves to find out. Fortunately, Heard wasn’t swayed by either. He had one more album up his sleeve.

(1991) proved to be even warmer and more intimate. The title is derived from the track that would come to be his signature tune, the paean to wonderful love in the midst of banal reality “Nod Over Coffee“. In keeping with his newfound desire to follow his muse, he includes a cover of the Beatles’ “I’m Looking Through You,” which in itself is a somewhat rude dressing-down sort of song. Even more jarring, but no less profound, is his original “What Kind of Friend.” The album represented something like a call to liberation within the CCM realm as artists started seeing how far one could go if they went there in the spirit of truth. Most of them paid dearly for it, while those that continued to play it safe reaped the benefits of hanging tight with the game plan. The secular world really had no clue these things were going on and, honestly, didn’t much concern themselves to find out. Fortunately, Heard wasn’t swayed by either. He had one more album up his sleeve.

Satellite Sky

Satellite Sky![]() (1991) became Heard’s best synthesis of the qualities found in Americana/folk sounds and the gutsy bounce of no-nonsense rock and roll. For music fans, the album was a total treat; 15 tracks, not a dog in the pack. If the brooding “Orphans of God” didn’t get you dancing, try “Language Of Love“. If “We Know Too Much” didn’t get under your skin, how about “Long Way Down“? All through the album, Heard’s crystalline mandolin playing offers a sound profile completely foreign to the music scene at the time, and his lyrics drip with a clear-eyed wisdom — something many of his counterparts avoided, often because they alluded to a humanity that is hard to market, an understanding that we don’t live in a fair and just world. Still, keep the heart prepared for the greatness to come, but celebrate what’s here right now, no matter how tattered it might appear.

(1991) became Heard’s best synthesis of the qualities found in Americana/folk sounds and the gutsy bounce of no-nonsense rock and roll. For music fans, the album was a total treat; 15 tracks, not a dog in the pack. If the brooding “Orphans of God” didn’t get you dancing, try “Language Of Love“. If “We Know Too Much” didn’t get under your skin, how about “Long Way Down“? All through the album, Heard’s crystalline mandolin playing offers a sound profile completely foreign to the music scene at the time, and his lyrics drip with a clear-eyed wisdom — something many of his counterparts avoided, often because they alluded to a humanity that is hard to market, an understanding that we don’t live in a fair and just world. Still, keep the heart prepared for the greatness to come, but celebrate what’s here right now, no matter how tattered it might appear.

Then came the summer of 1992. Mark Heard just finished his set at the Cornerstone music festival. All through his performance he was having chest pains, perhaps not fully realizing the severity of what was going on. When he was finished, he was taken to a local hospital where he subsequently died. It was one of those strange, sudden shocks, to the family, to the fans, like a very short rollercoaster on which you thought the greatest thrills were yet to come, but the ride was over. The tributes came quickly and effortlessly; wrapping one’s mind around the whole thing was much more difficult. The extent of the man’s reach was seen on the tribute compilation Strong Hand of Love: A Tribute to Mark Heard![]() (1994) and, to a greater extent, the expanded version titled Orphans of God

(1994) and, to a greater extent, the expanded version titled Orphans of God![]() . On it were old friends Burnett and Phillips, the Millers, Tonio K., contemporaries who were profoundly challenged by his example, the bands Daniel Amos and Chagall Guevara, Michael Been from the Call, and those who Heard helped shepherd, Vigilantes of Love and Kevin Max (Smith) formerly of DC Talk.

. On it were old friends Burnett and Phillips, the Millers, Tonio K., contemporaries who were profoundly challenged by his example, the bands Daniel Amos and Chagall Guevara, Michael Been from the Call, and those who Heard helped shepherd, Vigilantes of Love and Kevin Max (Smith) formerly of DC Talk.

His impact may not be huge in the grand scheme of things, and if it had been he might not have had the fortitude to strike out on his own to create albums of lasting value and creative permanence. Eighteen years later, the musical landscape is vastly different; certain divides no longer exist, while others have risen and taken their place. Fortunately, what has been left behind is still pretty great, a testament to art over artifice, and in its own way a love song to whatever’s yet to come.

Bruce Cockburn – Strong Hand Of Love

Related articles

- Dw. Dunphy On… It’s a Smaller World (popdose.com)

- Popdose 2010: Dw. Dunphy’s Top Albums (popdose.com)

- 50CCM50, Part Two (popdose.com)

Comments