Back in the early 90s, when I lived in Hong Kong, Prince Charles and Lady Diana paid a royal visit. If they were visiting some other part of the vanishing British empire, or a Western city like New York, this would have been front-page news, but for the local Chinese, already looking toward the 1997 handover to China, it was a shrug. I lived on an offshore island, and ferried in and out from Hong Kong Island from the famed Star Ferry Terminal. Cue “Love is a Many-Splendored Thing”–and it was a many-splendored thing indeed the evening they arrived. I was about to take my ferry back when they alighted from the royal yacht; their security detail was small, and other than a phalanx of reporters the crowd was sparse. I stood all of twenty feet from them as they got off the yacht, were welcomed by officialdom, and were whisked away in a limousine. “Wave and smile, wave and smile,” counsels the title character in the excellent film adaptation The Madness of King George (1994)–but there were few people to wave and smile at, other than one gawking American, who was wondering, “What is it about these people that fascinates us so?”

Back in the early 90s, when I lived in Hong Kong, Prince Charles and Lady Diana paid a royal visit. If they were visiting some other part of the vanishing British empire, or a Western city like New York, this would have been front-page news, but for the local Chinese, already looking toward the 1997 handover to China, it was a shrug. I lived on an offshore island, and ferried in and out from Hong Kong Island from the famed Star Ferry Terminal. Cue “Love is a Many-Splendored Thing”–and it was a many-splendored thing indeed the evening they arrived. I was about to take my ferry back when they alighted from the royal yacht; their security detail was small, and other than a phalanx of reporters the crowd was sparse. I stood all of twenty feet from them as they got off the yacht, were welcomed by officialdom, and were whisked away in a limousine. “Wave and smile, wave and smile,” counsels the title character in the excellent film adaptation The Madness of King George (1994)–but there were few people to wave and smile at, other than one gawking American, who was wondering, “What is it about these people that fascinates us so?”

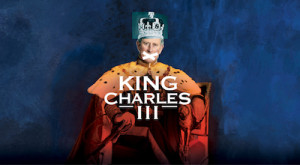

Dubbed “a future history play,” the impudent and funny King Charles III, a West End import, by necessity removes Diana from center stage, but her ghost ever hovers, on the periphery of the bare, medieval stage and at its emotional core. “I never thought she’d pass,” remarks Princess Kate to England’s new king toward the outset of the show, to which comes the mordant reply, “Nor did I.” Unbound in the autumn of his years, the eternally well-meaning Charles determines to put his stamp on the monarchy, but, in the way of all things for him, he puts his foot in it, and matters go askew. He refuses to sign an anti-hacking law put forth to him by the prime minister, which, though it would benefit the privacy-challenged royals, strikes him as repressive. Morally, it’s a proper, Charles-ish call, like his pro-environment stances. Politically, it’s a non-starter, immediately putting him at odds with a parliament accustomed to his mother’s rubber stamps, and Charles is as usual tone-deaf as to how to appeal to the citizenry. Over the course of the show’s five (brisk) acts a constitutional crisis develops, with the princely William and Kate consorting with the government, and the knockabout Harry, romancing a commoner art student, uncertain on the sidelines.

Dubbed “a future history play,” the impudent and funny King Charles III, a West End import, by necessity removes Diana from center stage, but her ghost ever hovers, on the periphery of the bare, medieval stage and at its emotional core. “I never thought she’d pass,” remarks Princess Kate to England’s new king toward the outset of the show, to which comes the mordant reply, “Nor did I.” Unbound in the autumn of his years, the eternally well-meaning Charles determines to put his stamp on the monarchy, but, in the way of all things for him, he puts his foot in it, and matters go askew. He refuses to sign an anti-hacking law put forth to him by the prime minister, which, though it would benefit the privacy-challenged royals, strikes him as repressive. Morally, it’s a proper, Charles-ish call, like his pro-environment stances. Politically, it’s a non-starter, immediately putting him at odds with a parliament accustomed to his mother’s rubber stamps, and Charles is as usual tone-deaf as to how to appeal to the citizenry. Over the course of the show’s five (brisk) acts a constitutional crisis develops, with the princely William and Kate consorting with the government, and the knockabout Harry, romancing a commoner art student, uncertain on the sidelines.

Author of another cheeky play I enjoyed, Cock, Mike Bartlett has written King Charles III in blank verse, and there’s much metered poetry (and a few choice one-liners) to go along with the audacious premise. Rupert Goold, who directed a stunningly stylized Macbeth with Patrick Stewart a few seasons back, keeps the staging Old Globe-simple, with haunting chorale music further setting a Shakespearean tone from the start. The storyline, however, is in High Modern Conspiracy Mode, with more than a dash of tabloid pluck. It wouldn’t get very far without a cast that could pull it off, but they do: character actor Tim Pigott-Smith, a familiar face from The Jewel in the Crown to Downton Abbey, takes Charles in an unexpectedly poignant direction as the crown lies uneasily atop his head, and William (Oliver Chris), the commonsensical Camilla (Margot Leicester), and Kate (Lydia Wilson), the inheritor of Diana’s values, are all at his level. Best of all is Richard Goulding’s conflicted Harry, a little bit Prince Hal and a little bit Falstaff, torn between duty and his jaundiced lover (Tafline Steen). I can picture the actual Harry having a laugh at the show, and enjoying his not unsympathetic portrayal. What is about these people that fascinates us so? Maybe that they live low and cunning lives in much better clothes and surroundings.

Comments