“You can’t see everything,” I lament, as plays and musicals I might be seeing slip away from me. But I have seen a few things.

“You can’t see everything,” I lament, as plays and musicals I might be seeing slip away from me. But I have seen a few things.

I heard from the great Patti LuPone a few days before I saw her in her latest play, Shows for Days, which closes next weekend at Lincoln Center. You probably did, too, as she declared war on cellphones and other distractions in the theatre, a campaign that made headlines. (Joining her was Hamilton co-star Jonathan Groff, who called Madonna a “bitch” for texting throughout a preview of the show. It’s not just the hoi polloi who behave badly…though I don’t think even Madonna would be quite so stupid as to mistake a phone charger that’s part of the set design for Broadway’s Hand to God for the real thing and try to use it before a performance, as some brainiac did.)

Quite right she was…but I must admit that by the second act of the show, I was hoping for a cellphone to go off, to shake things up a bit. In this autobiographical dramedy by Douglas Carter Beane (The Nance), LuPone is Irene, a theatrical diva…in Reading, PA, circa 1973, performing The Great God Brown and other obscurities for ever-dwindling audiences. Irene’s backroom machinations keep the place open, as a haven for oddball performers and stagehands who would otherwise be on their own adjacent to Amish country. One of these is Car (Michael Urie), a stage-struck high schooler whose artistic aspirations Irene encourages, so long as they don’t interfere with her constant scheming.

Urie, so wonderful in the one-man Streisand riff Buyer & Cellar, is a skilled actor, and as adorable as a box of puppies as he experiences first love, and first rejection, with the company’s sexually ambiguous leading man, Damien (Jordan Deane). But Car is an overly generous narrator, not giving himself much of a role until the second act, by which time Deane has frittered away too much time on Irene’s confused jockeying for position in the Reading pecking order. He seems to have something to say about community theatre and its impact on the cultural life of small towns, but never finds a compelling, much less coherent, way to say it. Much easier to write zingers for gay characters, a butch lesbian with a tool belt and a “flamboyant” black actor, who were stereotypes even in 1973.

Bedecked in William Ivey Long’s chintzy grande dame clothes, the star is a queen bee throughout; too bad drones are the company she keeps. Lots of top-drawer talent here (director Jerry Zaks, set designer John Lee Beatty, etc.) in a minor off-season diversion that besides the din of cellphones does not give LuPone much to shout about.

Bedecked in William Ivey Long’s chintzy grande dame clothes, the star is a queen bee throughout; too bad drones are the company she keeps. Lots of top-drawer talent here (director Jerry Zaks, set designer John Lee Beatty, etc.) in a minor off-season diversion that besides the din of cellphones does not give LuPone much to shout about.

I think we’ll be seeing the Hamilton Effect for a few seasons to come–that is, the notion that summer can birth a hit Broadway musical. Yes, it’s a spectacular success–but it was an award-winning phenomenon in spring, and fueled by great word of mouth and supportive media it made a smooth transition from downtown to midtown.

It’s also the first spectacular summer success I can recall since Hairspray (2002), which was buoyed by a bit of brand-name recognition and a plus-sized Broadway musical star in Harvey Fierstein. Few tuners that plant their flag in tourist season have these elements in their favor, and yet they come in. Case in point: the musical that opened the 2015-2016 season, Amazing Grace, which doesn’t have a wing and a prayer of a profitable run.

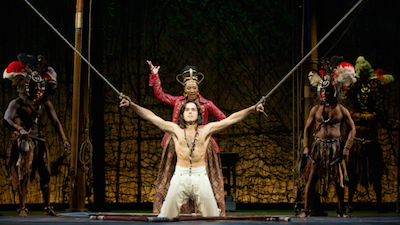

I could see, maybe, a musicalization of Michael Apted’s fine 2006 film, about the abolition of slavery in early 19th century Britain. That Amazing Grace uses John Newton, the slave ship captain-turned-Christian convert who wrote the legendary hymn, for a supporting turn, by a scene-stealing Albert Finney. This Amazing Grace, a DIY show for Pennsylvania cop-turned-composer Christopher Smith, is focused on Newton, and boils down his life to a protracted father-and-son conflict. Dad (Tom Hewitt, a veteran of Frank Wildhorn’s Dracula, a summer musical fiasco) doesn’t want his fortune-seeking son hanging around the slave ships where he made his money; son (Josh Young, a Tony nominee for the recent revival of Jesus Christ Superstar, where he played Judas) does anyway, and becomes an expert slave trader. Shipwrecked in Africa, Newton himself becomes a slave, and then a Christian convert, and in time upon his return to England a better match for his true love, a secret abolitionist (Erin Mackey). Curiously, we never see much of the writerly gifts that brought us “Amazing Grace,” which after many rote inspirational numbers (sample titles: “Truly Alive” and “I Still Believe”) gives the show its climax.

I could see, maybe, a musicalization of Michael Apted’s fine 2006 film, about the abolition of slavery in early 19th century Britain. That Amazing Grace uses John Newton, the slave ship captain-turned-Christian convert who wrote the legendary hymn, for a supporting turn, by a scene-stealing Albert Finney. This Amazing Grace, a DIY show for Pennsylvania cop-turned-composer Christopher Smith, is focused on Newton, and boils down his life to a protracted father-and-son conflict. Dad (Tom Hewitt, a veteran of Frank Wildhorn’s Dracula, a summer musical fiasco) doesn’t want his fortune-seeking son hanging around the slave ships where he made his money; son (Josh Young, a Tony nominee for the recent revival of Jesus Christ Superstar, where he played Judas) does anyway, and becomes an expert slave trader. Shipwrecked in Africa, Newton himself becomes a slave, and then a Christian convert, and in time upon his return to England a better match for his true love, a secret abolitionist (Erin Mackey). Curiously, we never see much of the writerly gifts that brought us “Amazing Grace,” which after many rote inspirational numbers (sample titles: “Truly Alive” and “I Still Believe”) gives the show its climax.

With a nautical set that recalls Sting’s flop The Last Ship, and storm-at-sea effects reminiscent of the flop Coram Boy, design and direction (by Gabriel Barre) lack similar inspiration, and choreographer Christopher Gattelli had more to work with his last time out at the Nederlander, with Newsies. As Newton’s manservant, the great Chuck Cooper (summer musical flop, Lennon) wakes up the audience with his second act number, “Nowhere Left to Run”–but by that time, there’s nowhere left to run with the show. Far from Broadway, where The Book of Mormon passes for a faith-based show, I think there may be an audience for this, in some form, and that its appearance here is an advertisement for regional engagements. We’ll see…yet for now I’m all for abolishing lackluster summer musicals on Broadway.

You can’t see everything…so, somehow, having seen all her prior work, I missed The Flick, for which playwright Annie Baker won the Pulitzer Prize. No way, then, was I letting John, part of her residency at the Signature Theatre, out of my sight.

As Baker’s reputation has grown, so has the length of her plays–like The Flick, John runs almost three and a half hours, with two intermissions. The plot I can explain in a sentence or two. Elias (Christopher Abbott, from Girls) and Jenny (Hong Chau, Treme) find themselves the only guests at a Gettysburg B&B run by Mertis (Georgia Engel). Love is a battlefield for Elias and Jenny, who are trying to get over some sort of rupture in their three-year relationship, but Elias keeps picking at the scabs. Sidelined by painful menstrual cramps, Jenny lets Elias tour the sites on his own, and at the inn is drawn into conversing with Mertis and her blind friend, Genevieve (Lois Smith). Elias returns.

As Baker’s reputation has grown, so has the length of her plays–like The Flick, John runs almost three and a half hours, with two intermissions. The plot I can explain in a sentence or two. Elias (Christopher Abbott, from Girls) and Jenny (Hong Chau, Treme) find themselves the only guests at a Gettysburg B&B run by Mertis (Georgia Engel). Love is a battlefield for Elias and Jenny, who are trying to get over some sort of rupture in their three-year relationship, but Elias keeps picking at the scabs. Sidelined by painful menstrual cramps, Jenny lets Elias tour the sites on his own, and at the inn is drawn into conversing with Mertis and her blind friend, Genevieve (Lois Smith). Elias returns.

That’s the story. But it’s the thingness of John that requires time, and elaboration. It’s late November, and Mimi Lien’s exquisitely designed set is laden with a Christmas tree with lights that blink on and off and tchotchkes that, as illuminated by Mark Barton, seem to be looking at us as we look at them–appropriate for a show where the characters discuss the notion of a metaphysical “watcher,” different from God, who observes our activities. With talk of secret rooms, the B&B seems to be haunted, an idea underscored by Mertis and Genevieve reading from Lovecraft, talking in unknown languages, and Mertis speaking of her ailing, suggestively unseen second husband as her elder companion discusses a period of mentally debiliating possession by the spirit of her ex-husband, John. Ghosts hang in the atmosphere.

But Baker plays her cards close to her chest. No doubt some audience members will find John too much of a shaggy dog story, and there were a handful of walkouts. The silences, and lack of emphatic dialogue or major themes, can be exasperating. I was intrigued, and found that Baker’s usual director, Sam Gold, kept his usual firm hand on the very deliberate pacing. There’s always something to look at, or ponder, and the four performers are savory. It’s the veterans who draw us into this world, however. Smith, a theatrical treasure, makes the most of her offbeat characterization, though not too much; she goes almost to the top. And Engel is in peak form. Forever Georgette on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, she maintains that same pixelated speaking voice, and has developed a physical presence as graceful, and as comic, as Stan Laurel’s. (Seen on Broadway in The Drowsy Chaperone, and more recently cast in Baker’s adaptation of Uncle Vanya, she also winds the clock on the set and tends to the curtains between acts.) You can watch this underrated performer forever, and thanks to the generous running time of John, you can. More good news: The Flick is back Off Broadway, so maybe I can see everything.

Comments