There was an odd cultural moment about twenty years ago when veterans of the 1970s rock avant-garde started showing up in an unexpected place — the pop charts. That old fuso-muso whorehorse Jan Hammer scored a big hit with his Miami Vice theme. Adrian Belew was on MTV with his suit and his pink guitar, and there was Rod Morgenstein, late of the Dregs, drumming for Winger, fa chrissakes.

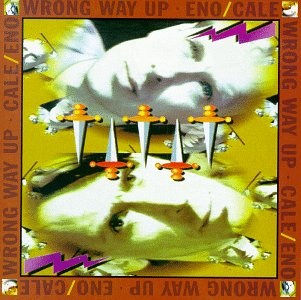

It was in these days of miracles and wonder that composer and ambient-music theoretician Brian Eno — he of Music for Airports fame — would team with Velvet Underground alum and noise-rock terrorist John Cale — he of chicken-murdering, viola-torturing, hockey-masked infamy — to release 1990’s sunniest, shiniest pop album.

No, seriously.

For those who’d been paying attention to the artists’ careers beyond those caricatured highlights, Wrong Way Up was only mildly surprising, but still delightful. For all his ferociously cerebral popular image, Eno had always embraced hooks along with formal experimentation; albums like 1974’s Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) and 1977’s Before and After Science paired nonsense words with melodies as naÁ¯ve and sturdy as nursery rhymes, and he was a key collaborator with Talking Heads in their most fruitful period of applying art-rock strategies to dance-pop forms. And Cale, despite the figurative and literal violence of his methods, had a strong element of pop classicism within his omnivorous musical approach.

In particular, both men showed the influence of Brian Wilson, and Wrong Way Up, in a sideways fashion, pays off-kilter homage to the Beach Boys. From the opening ”Lay My Love” (download), which pairs a Wilsonian stack-o-vocals against a static pulse straight out of Philip Glass, Eno’s approach is playful and summery. Take a listen to that vocal arranging, and the way that straight harmonies give way to braided parallel melodies as Eno’s choirboy tenor and Cale’s whiskey baritone play off and against one another — peaking in the dangling conversations of ”One Word,” the album’s first single and video.

Cale’s songs, by contrast — and although everything is credited jointly and the sensibilities mesh well, there are definitely tracks here that belong more to one than the other — rely on spare arrangements and some of the strongest melodies of his long career. Aside from the joycore explosion of ”Been There Done That” (download) — which really should have been the single — they lean towards the dark textures of his solo work.

One of Wrong Way Up’s strongest moments melds Cale’s usual geopolitical skulduggery with Eno’s more ludic approach; ”Cordoba” (download) is built around phrases from a conversational-Spanish phrasebook. Like EugÁ¨ne Ionesco’s absurdist play The Bald Soprano, it wrings an odd emotional power from those most banal of language, sketching a doomed love affair that may also be a terrorist plot. Interestingly, although the subject matter and style suit Cale down to the ground, and the song has become a staple of his live performances, it was allegedly Eno who assembled the lyric.

Aside from Cale’s streak of gangster perversity, most of Wrong Way Up is devoted to the pleasures of domesticity. Characters wander the Louvre and tour country houses, admiring the oil paintings and the play of light on the surface of the swimming pool, or stroll by a cool riverbank in the dusk listening to the peacocks cry. It’s all very civilized, all very First World; but the best songs here find resonance and wisdom in tiny, everyday moments. ”Spinning Away” (download) — later covered by Sugar Ray, although you’d be forgiven for not remembering their version — may be the finest evocation of the mystical experience ever put to music.

We find the singer on a hill, drawing pad in hand, sketching the landscape as the sun goes down. And as the Afropop guitars chime away and the stars wink into life, the sense of scale changes and expands. You listen, and your head stretches to hold more of the world in it. In ordinary consciousness, we’re generally only acutely aware of our environment within a nine-foot circle around our bodies. In the mystical state, you’re aware of your place in the larger schema; you’re a man on a hill on an island on a spinning planet circling amongst the stars. You feel small, but it’s okay, because you are exactly where you are supposed to be. Everything is going according to plan.

And the clock ticks over midnight, and one year becomes another, and everything is all right. Everything is as it should be, and the plan is in place. In all places, all at once. Every way is the right way, and every way is up.

Comments