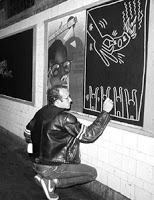

So I’m standing on the 7th Avenue subway platform in lower Manhattan, circa 1983. Two knuckleheads are discussing a picture of a baby in a circle. The primitive image is drawn in white chalk on the black paper pasted over an advertising billboard mounted to the tiled wall. ”I think it means: No Babies On The Tracks,” says the dumber of the two. After considering that for a moment, the other fool says, ”Uh…it looks like a wristwatch.” All the while your humble narrator was thinking, ”Would you chumps mind stepping aside so I can try to get that Keith Haring original off the wall before my train comes?” They didn’t so I couldn’t.

So I’m standing on the 7th Avenue subway platform in lower Manhattan, circa 1983. Two knuckleheads are discussing a picture of a baby in a circle. The primitive image is drawn in white chalk on the black paper pasted over an advertising billboard mounted to the tiled wall. ”I think it means: No Babies On The Tracks,” says the dumber of the two. After considering that for a moment, the other fool says, ”Uh…it looks like a wristwatch.” All the while your humble narrator was thinking, ”Would you chumps mind stepping aside so I can try to get that Keith Haring original off the wall before my train comes?” They didn’t so I couldn’t.

I’m wondering, had I been able to remove the drawing, if I’d be able to do anything with it besides hang it in the private galleries at stately Keepit Manor. And I’m wondering about that now because, thirty years later, the question has come up in connection with a mural by street art superstar Banksy. Check it:

‘Slave Labour’ shows a poor urchin sewing Union Jacks on an antique machine, presumably a satire of Queen Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee last year. The shadowy Bristol artist stenciled it on the wall of a shop in the northeast London borough of Haringey, not far from where Tottenham enjoys thrashing Arsenal. Unnamed persons removed it from the shop wall in January and it surfaced in February. In Florida. In an auction house. For sale. For half a million dollars. Dayum!

This is not the first time someone has messed with Banksy’s work. Rival Bristol artist(s) Robbo deliberately painted over one of his drawings. See:

In 2007, London transit workers mistakenly painted over Banksy’s famous Pulp Fiction mural showing Samuel L. Jackson and that Scientology guy holding bananas instead of guns. A Transport of London spokesman was unapologetic: ”Our graffiti removal teams are staffed by professional cleaners, not professional art critics.” Cor blimey, guv’nor! Over the years, countless Banksy works have been erased, defaced or disgraced. There’s a good Wikipedia entry about that here.

It’s also not the first time someone griped about unauthorized use of popular graffiti. In 2011, Bronx taggers TATS Cru objected to Fiat’s tv ad showing its speef little 500 rolling through the ’hood, ostensibly with Jennifer Lopez behind the wheel. J.Lo wasn’t actually driving (she was in a soundstage out here in LA), but the car did cruise by the Cru’s BRONX mural, like so:

The mural had a copyright notice in plain view and TATS Cru wasted no time suing Fiat for infringement. The beef was settled when Fiat’s corporate parent Chrysler gave the aerosol champs a free car to paint and auction for charity.

I sense the astute and attractive readers of KI2Y are non-plussed about the Slave Labour’ situation. If the painting is put up on a wall facing a public street, with no attribution (let alone no copyright notice), isn’t it by definition in the public domain? Or, since it’s affixed to private property, does it belong to the building’s owner? And, if it does belong to the owner, can he or she sell it or make copies of it, or is copyright vested in the artist? In other words: Who Owns The Writing On The Wall? (Hint: It’s not Roger Waters.)

Here’s the short answer: Graffiti may be seen as free speech, or criminal vandalism (or both). As a practical matter, when a street artist does his thing on a wall it’s basically a gift or a nuisance to the wall’s owner. Dude can paint over it or tear it down. He can cut out that section of the wall and sell it. Dude can do anything with the thing itself, but that’s it. Copyright — literally the right to make copies — remains with the artist. So, wallboy can’t reproduce the image on t-shirts and coffee mugs or, in Banksy’s words, license it ”for a huge fee to a fucking German calendar company.”

What if the graffiti actually increases the value of the property? Around the world, there are many high-profile artists — BLU and Space Invader in Europe, The Ratchet Art Partnership in Chicago, Os Gemeos in Brazil — who might crank up the price of a building by dropping a masterpiece on it. In that case, who should benefit? Up in London N22 8LE where Slave Labour’ was surreptitiously heisted, they see it this way: ”There’s a sense of outrage among local people,” said Claire Kober, head of Haringey Council. ”Banksy gives these paintings to communities. They’re cultural assets that generate a huge sense of civic pride. Morally, if not legally, we act as guardians rather than owners.”

Lady Claire’s take is consistent with Banksy’s own attitude towards his street oeuvre. His website specifically invites any one to ”Please feel free to: copy any Banksy imagery in any way for any kind of personal amusement. Make your own Banksy merchandise for noncommercial purposes. Pretend you drew it yourself for art homework.” But he also wrote: ”Please do not: put up signs saying ‘strictly no photographs’ when all you do is sell photographs of my graffiti.” To prevent folks from jacking his biz for profit, in 2008 Banksy established Pest Control, a service that authenticates his works. By giving his official imprimatur, Banksy can confirm attribution or refute misattribution. Major auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s won’t put his gallery pieces on the block without PC’s green light. Pest Control generally declines to authenticate site-specific pieces because Banksy intends that his public works remain in their original contexts: ”Pest Control has done a good job regulating the market for Banksy street works that weren’t intended for sale,” said Mike Snelle, director of the London-based gallery Black Rat Press. ”If they haven’t got certification, they’re difficult to sell. You don’t know if they’re real.” Case in point: Scottish auctioneers Lyon & Turnbull tried to sell a group of site-specific works by Banksy. Pest Control refused to endorse them and no one put down a bid. PC was pleased: ”Banksy prefers street work to remain in situ, and building owners tend to become irate when their doors go missing because of a stencil.”

Which brings us back to the recently-jacked ‘Slave Labour.’ This piece was not authenticated by Pest Control. However, Fine Art Auctions Miami stated that it ”has done all the necessary due diligence about the ownership of the work” and put the authenticity burden on anyone who would challenge it: ”Unfortunately, we are not able to provide you with any information, by law and contract, about any details of this consignment. We are more than happy to do so however if you can prove that the work was acquired and removed illegally.” Harumph.

‘Wet Dog”, another presumed Banksy piece, was pulled from FAAM’s Miami auction when Pest Control refused to authenticate it.

Nonetheless, FAAM ended up yanking ‘Slave Labour’ off the auction block. This gesture answers our question: the owner of the physical property to which the artwork is affixed owns the art and may sell it, if he or she finds a willing buyer. The owner can also destroy it or cover it up if they so choose. But the owner cannot reproduce the artwork because that would violate the artist’s copyright. English copyright law is similar to the American version: Their definition of an ”artistic work” covers a broad range of graphic works, provided they are affixed to a surface (or ”fixed in any tangible medium of expression,” as we say in the Colonies). There, as here, graffiti may be afforded copyright protection as an artistic work, provided it was created with the requisite amount of ”skill, labour and/or judgment.” In short, copyrights exist as soon as the art hits the wall.

Here’s how the Haringey shop looks now:

No word if the ‘Thieves’ bit or the inquisitive rat are Banksy originals. Whatevs. I should have nabbed that Haring baby and caught a later train.

Comments