My dad was an opera singer when he was a kid and later turned into a huge folk music fan. He taught himself to play guitar and would sing all the time to my sister and me when we were little. My parents thought music was extremely important, so we had to pick an instrument by age 10 and take lessons for at least a year. My older sister was already taking guitar lessons, so I had to pick something completely different. I got dragged to a party with my parents when I was about nine. Like many of these parties, I was the only kid there. The host, Mel, could see I was bored out of my mind, and took pity on me. He came over and said, “Do you want to see something really cool?” I followed him up to the attic and as I turned the corner at the top of the stairs, I saw him pull a sheet off of this beautiful, old, glittery white Slingerland drumset. I couldn’t breathe and time seemed to hold still. Right then, I knew I was going to play the drums.

After a couple of years I started to take playing pretty seriously, and ended up majoring in music at USC. At my senior recital, Mel came up to me and reintroduced himself. We talked a little about drums; unfortunately, I never saw him again. A few months after I graduated, I got a phone call telling me that Mel had died and he had left me the Slinglerland kit in his will. So everything had come full circle, and I started playing on the kit that made me fall in love with the instrument in the first place.

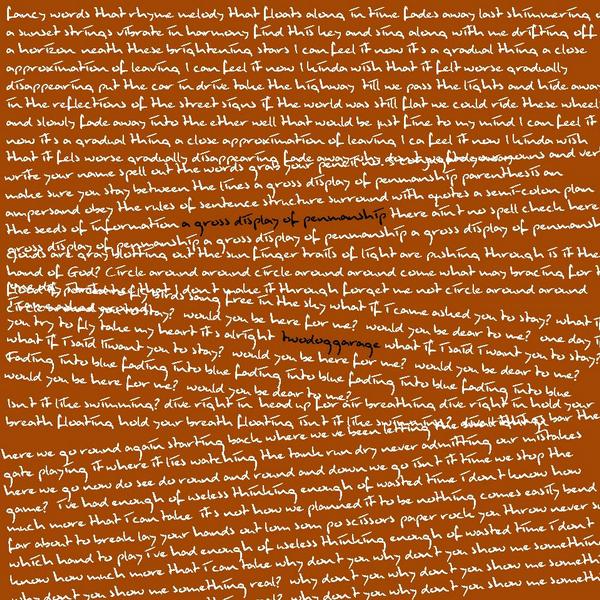

![Pinboy-by-Twodoggarage_dffq3CMcOs0x_full[1] Pinboy-by-Twodoggarage_dffq3CMcOs0x_full[1]](https://popdose.com/wp-content/uploads/Pinboy-by-Twodoggarage_dffq3CMcOs0x_full1.jpg) That’s the beginning of the story of singer/songwriter Alex Kimmell, a.k.a. twodoggarage — and only the beginning. You’ve likely never heard of Alex, or listened to his music; in practical terms, he’s just another guy with a day job and a dream, one without the bucks or the luck to push his way through the crowd and into your stereo. Scratch beneath the surface, though, and you’ll find some uncommonly beautiful songs, delivered with a graceful hand and an open heart — the kind of songs you can tell have intensely personal meaning, expressed with the kind of universal sentiment that draws you back to them again and again. Songs like my personal favorite, “Everything Happens to Me” (download), from 2008’s Pinboy. This song has come up on my iPod dozens of times since I first heard it, but there’s something about it that strikes a deep chord in me. Every time I hear Kimmell’s clear, plaintive voice, the gently surging melody, and the way he sings the refrain…

That’s the beginning of the story of singer/songwriter Alex Kimmell, a.k.a. twodoggarage — and only the beginning. You’ve likely never heard of Alex, or listened to his music; in practical terms, he’s just another guy with a day job and a dream, one without the bucks or the luck to push his way through the crowd and into your stereo. Scratch beneath the surface, though, and you’ll find some uncommonly beautiful songs, delivered with a graceful hand and an open heart — the kind of songs you can tell have intensely personal meaning, expressed with the kind of universal sentiment that draws you back to them again and again. Songs like my personal favorite, “Everything Happens to Me” (download), from 2008’s Pinboy. This song has come up on my iPod dozens of times since I first heard it, but there’s something about it that strikes a deep chord in me. Every time I hear Kimmell’s clear, plaintive voice, the gently surging melody, and the way he sings the refrain…

I think there’s a solution

Love is evolution

Leave behind the disillusionment

I don’t mean to complain

Once again, everything happens to me

When blue skies turn to gray

Once again, everything happens to me

…I’m moved all over again.

As I said, those first paragraphs were just the start of Kimmell’s story; after graduating USC, he toured the jazz circuit in Europe for a few years before moving back to L.A. and becoming, in his words, “burned out on the whole scene.” He eventually wound up behind the kit for Stewboss, but when forced to choose between going back overseas for a tour or staying home with his pregnant wife, he knew there was really only one choice — and he made it, embarking on a solo career with the support of his wife and friends.

Gregg Safarty, my friend and the leader of Stewboss, sat me down and basically said, “You need to be doing your own music anyway. Do your own thing. You can do it.” I had recorded some of my own material on a four-track, but never had the confidence to be in front of the band — I was used to being behind the kit in a supporting role. But with Gregg and my wife’s encouragement, I started playing solo acoustic shows around town and putting my own band together. This was new for me, but I started to love it pretty quick. My bass player, Scott Burns, was a recording engineer and we used to go into the studio he worked at during off hours and started recording both of our original tunes. I learned a lot about recording from him. Adam Castillo, my guitar player at the time, worked at M-Audio; he offered me a gig as an Artist-In-Residence for them. They gave me a computer and some recording gear, and got me started on home recording.

“Home recording,” in Alex’s case, meant essentially moving his gear into a closet and recording after his family went to bed. Still a drummer at heart, he’d track his drums at a rehearsal space, but everything else was created in small spaces, at odd hours, as time allowed. Unlike a lot of DIY artists I’ve listened to, Alex has a sharp ear for sonic depth and color; rather than just capturing the performance — or refining it until nothing’s left — he knows when to bring the noise, so to speak, and when to give his melodies more room to breathe. Take “Gradually Disappearing” (download), for example: you can tell he’s given the recording some thought, but he uses his instruments to support and enhance his message, and gives you just enough of the sweet stuff — subtle synths, droning guitars — to keep you engaged without overwhelming the frayed charm of the vocals or the fragile beauty of the melody. It’s got an almost airy quality, which is somewhat ironic given the way he records.

I record using Cubase 5 and Reason 4 on my Mac through a TASCAM FW-1082 control surface at home. I also share a small studio/rehearsal space with my friend Brett Merritt and his band Hindge Creek where we have a TASCAM DM3200 and a Cubase system, which is where all of the drums were tracked. I don’t have any super expensive microphones or pre-amps or anything like that. For vocals, I use an MXL V-69 tube mic, which is amazing, and for drums we pretty much used SM-57Á¢€â„¢s on the snare and toms. The overheads were a matched pair of M-Audio Pulsar II’s and the kick mic was a Sure Beta 52, all of which went straight into the DM3200 into Cubase. I have a pair of first generation M-Audio Studiophile SP-5B monitors that I use, but since a lot of my recording is done at night and my studio is literally in my bedroom’s walk-in closet, I use headphones most of the time.

I record using Cubase 5 and Reason 4 on my Mac through a TASCAM FW-1082 control surface at home. I also share a small studio/rehearsal space with my friend Brett Merritt and his band Hindge Creek where we have a TASCAM DM3200 and a Cubase system, which is where all of the drums were tracked. I don’t have any super expensive microphones or pre-amps or anything like that. For vocals, I use an MXL V-69 tube mic, which is amazing, and for drums we pretty much used SM-57Á¢€â„¢s on the snare and toms. The overheads were a matched pair of M-Audio Pulsar II’s and the kick mic was a Sure Beta 52, all of which went straight into the DM3200 into Cubase. I have a pair of first generation M-Audio Studiophile SP-5B monitors that I use, but since a lot of my recording is done at night and my studio is literally in my bedroom’s walk-in closet, I use headphones most of the time.

When I recorded my guitar parts I went straight into the FW-1082 and used Amplitube 2. Once again, I would love to crank up a Fender or Marshall stack, but with the limitations of recording in a closet, the virtual amps are incredible! If you take some time and mess around enough, you can get some pretty amazing tones out of those things.

Having worked with a number of indie musicians — and recorded albums of my own — I know how easy it is to let time lapse between releases. You’ve got annoying real life issues to deal with, of course, and then there’s always the problem of not knowing when the music is actually done. I’ve known guys who labored over albums for years — a decade or more — and ended up getting so close to the material that they couldn’t tell what they were hearing anymore. Point being, it helps to have some sort of external impetus to push you toward the finish line. Personally, I liked to schedule a release party before the record was actually in my hands; it had the negative side effect of often producing comical and unintended consequences, but once deposits were paid and plans were made, there was nothing to do but cut the umbilical cord on the stated day and date. The “external impetus” thing is something Alex Kimmell understands intimately — A Gross Display of Penmanship was recorded as an entry in this year’s RPM Challenge, and Pinboy came together because he wanted something to sell at a benefit show he was organizing to raise money for a service dog for his oldest son, who is autistic.

Though he’s nominally a one-man band, Kimmell stresses that his records couldn’t get made without the support of talented friends: “Adam Castillo, Jon Mesh, Jim Maloy and Gregg Sarfaty played some incredible guitar solos and added textures that enhanced the songs in ways my abilities would never have let me do. Scott Burns has been my go-to bass player and good friend for years — he literally reads my mind and plays what I need without me even needing to tell him. Getting the record mastered made a huge difference as well — my friend Jim Bailey over at Random Precision worked painstakingly hard on getting the record to sound just right and I am forever indebted to him and his incredible ears.”

As I said before, you’ve probably never heard of Alex Kimmell or twodoggarage, and it’s altogether likely that — presuming you listened to the two songs I included in this post — today marks your introduction to his music. But he’s a guy making records for the right reasons, and doing a damn fine job of it, too. For that reason, I asked him if he had any advice for other DIY musicians, and I think his words do a perfect job of summing up what I like about his music:

Surround yourself with people who are honest. Even if you work very hard on something, and put your entire heart into it, it may not sound very good. You need to be sure that your friends or partners are willing and able to tell you the truth and not let your feelings get hurt in the process. Unfortunately this is probably the most difficult part of being an artist. But it’s also the most important.

Also, spend as much time as you can with other artists while they do their work. Spend time in recording studios and watch how other professionals get sounds and tweak sounds and experiment. Read recording books and, most importantly, spend time recording. Make recordings that you never plan to play for anyone and intentionally fuck up. Make mistakes. Put the microphone too close to the guitar. Sing into a shoebox.

I’ve never taken a recording class, but I was fortunate enough to have been a session musician and was able to be in studios a lot. After I lay down my drum parts, I would just hang out in the room and watch the rest of the session. I learned something new every single time.

Comments