In the fall of 1991, I was a high school senior, just starting to find my feet as a music writer — and as a listener, just discovering pathways into forms and genres I never knew existed during my Top 40 youth. The more I think about it, the more I think ’91 is the fulcrum my experiences as an adult music fan rest on — the year I, either by dint of willful experimentation or happy accident, started traveling into areas that stripped away that shiny, radio-ready artifice. Songs that grasped the emotional third rail. Artists who were trying to say something meaningful.

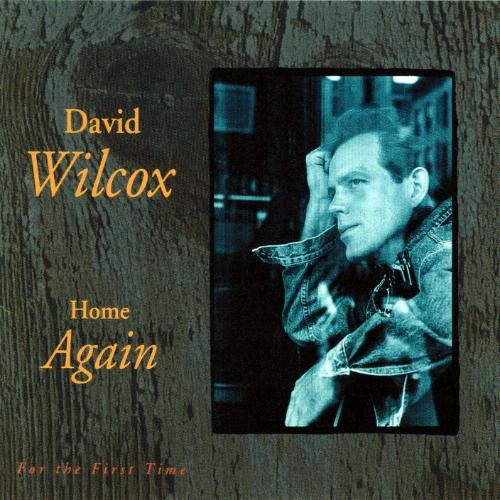

One of those happy accidents occurred in the fall of that year, when I spotted an ad in Billboard for an album by an artist I’d never heard of: David Wilcox’s Home Again. I didn’t know anything about him or the record, but there was something about the artwork, and the vibe Wilcox gave off in the ad, that made me think it might be worth calling A&M Records and requesting a copy for review.

I was already getting pretty jaded about new music at this point, and often skimmed albums and made lazy snap judgments about the artists. I had a lot to listen to, and I hadn’t yet developed a sense of responsibility about really doing the work. But I’ll never forget the first time I listened to Home Again, because it’s one of the few times I’ve sat down, started playing an album, and been so enthralled by the music that I didn’t get up — or lose focus — until the last song ended.

Why did the music move me so? I still think the songs are wonderful, but I’m sure it also had a lot to do with things that were going on in my own life, what kind of mood I was in that day, the angle of the afternoon sun through the window…you know, all those intangibles that change the angles that a song has to navigate to find purchase in the listener’s heart. But what matters is that Home Again was an important album to me, one that started a long love affair between me and David Wilcox’s music.

Naturally, I had to write a Popdose Flashback celebrating the album’s 20th anniversary — and David himself was gracious enough to sit for an interview about the music. Here’s what we discussed.

I’d like to begin by asking you how much of yourself you still hear in these songs. Twenty years is a long time…

I’d like to begin by asking you how much of yourself you still hear in these songs. Twenty years is a long time…

Well, it’s like they’re good photographs of me that don’t look like me anymore. I think it’s a really good portrait of how I got to the joy I’m feeling now, but a lot of the stuff I don’t need to sing anymore. At the time, it was a real indicator for me of stuff that was causing me a lot of pain, and I needed to work at. Now the work is done, and the songs are not my frontier anymore. Which is great.

It’s truly a beautiful album, but it’s also a rather dark one. Deceptively dark.

Well, the ones that I still play, like “Chet Baker’s Unsung Swan Song” — I love that. And writing it was such a fun experience. But it came from a time in my life when I was really facing the tendencies I have that are so destructive to my peace and my joy. That song was a big wake-up for me.

Has your writing process changed over the last 20 years?

Definitely. I think back then, I was still pretty much doing words first, which is a bad idea for me. I can definitely write a better song if I get the music right first, because the words stretch better, do you know what I mean?

I actually wanted to talk to you about that, because I know you’ve said that you wait for your guitars to tell you stories, and I wondered if any of Home Again‘s lyrics caught you by surprise. It sounds like the process was more willful.

Well, there’s always the surprise factor of where it’s going. I start with something I’m feeling, and I don’t know how it’s going to resolve — sort of what the lesson is. And in the process of writing, I get that clarity.

As you were creating these songs, did you feel like you were achieving a breakthrough as a songwriter? Your first two releases were certainly fine albums, but these songs — there’s a lot of really striking imagery in here.

I think that my perception at the time was that my second album was much better, and that this was not a step forward at all. I was really exhausted, I was touring hard, and I made the decision to record in New York City, which I wasn’t psychologically strong enough to manage well. So the feelings that I had about that record were that it could have been so much better.

I think the thing that was great about it was that I had gotten just a little blip of attention from How Did You Find Me Here, and I had decided that I was going to make the next album humbler and closer to — as if I were just talking to me friends and finding my tribe. So the songs aren’t trying to be too slick or polished or, you know, kind of pop. They were about my healing. My journey. And as a result, there were more people who would be sort of put off by them.

![davidwilcox-2010[1]](https://popdose.com/wp-content/uploads/davidwilcox-20101.jpg) That would be put off by them? You think so?

That would be put off by them? You think so?

Yeah, because they’re too close. I mean, a song like “Covert War” — it’s too much. You hear half of that, and you have to shut it off. It’s not the kind of song that’s going to make someone say “Ooh, let me hear that again! Let me bring up my toughest issue!” [Laughs]

We spoke last in 1998, and during that interview, you talked about the art of live performance — specifically, of gauging your audience to determine how far you can go into material like “Covert War” before you have to bring them back into something lighter and more humorous.

Yeah.

I think that’s an art expressed in Home Again‘s sequencing — the way it moves between more serious subjects and songs that are almost like comedic interludes. It seems like there was a lot of deliberation and a lot of craft put into the way those songs flow together.

You know, that’s interesting — I’ve never thought of it that way. But there are songs that are way too happy. [Laughs] Like “Top of the Roller Coaster,” with that weird little calliope noise, it’s like over the top. But seen in context, it does make a little more sense.

Well, let’s talk about craft. How hard did you have to work for these songs? Was a lot of labor involved, or did they just sort of fall out of you?

Oh, everything about it was just killing me. Except for “Advertising Man,” which was just a fun little one-take number I did with my friend Bill, who was kind enough to come to New York for the session.

What’s striking to me about “Advertising Man,” and the funny songs on this album in general, is that they aren’t just funny songs. Even as you were going for the laugh, you always included some really sharp lines. They aren’t throwaways.

Well, that — “Advertising Man” is passive-aggressive. I was really angry, and I just made it a funny song because I was too much of a wimp to sing it straight. Musically, it was hiding in a kind of a costume — it had a character about it hearkened back to 30 years before.

Not unlike something Randy Newman might do.

I wish! Randy would have made it a lot more complex, and made it from the point of view of someone who was dying of cancer! [Laughs]

So how long did it take you to write these? Did they come in one stretch, or were some of them older?

No, it’s always a gradual process — there were some that I had before, and there were some that just barely made the cut in terms of the time limit. There were lots to choose from. And there were some that I slaved over, and some that came unbelievably quickly. Like “Chet Baker’s Unsung Swan Song” — that’s the fastest song I ever wrote. It took as long to write as it would to copy down, and I heard the music as it was coming out.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/W0fJc-62ewY" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

When we talked in ’98, you made a comment about there being a lot going on in the recordings you made with Ben Wisch, who produced Home Again. At the time, I was taken aback, because I’ve always thought of it as a really pure, uncluttered album — but listening to it now, it’s clear that the arrangements are really layered. What was the recording process like for you? Were you in the studio the whole time?

Yeah, it was a residence. I moved to New York and got an apartment, which was another bad idea [laughs]. I was just unbelievably lonely, and it wasn’t a good place for my…I mean, my heart was just so ripped open. I was all confused and I didn’t know who to trust, and musically, it was really challenging.

You know, Ben — the best of what he does is just not get in the way. He’s got great ideas musically if you ask him, but whenever a musician comes in to do a track or an overdub or whatever, they’ll ask him, “So what do you want? What’s the feel?” And he’ll say, “Well, why don’t you just try whatever comes to you?” He explained to me that it’s easy to get someone to do what you want them to. The reason you pay triple scale is so they give you something you never would have thought of. You don’t want to give them any ideas first.

And this is a great thing. Except in my case, I was so emotionally fragile that I just needed somebody to say “This is a great song, sing it to me,” instead of just leaving me in the darkened silence with a microphone. But, you know, I think one of the reasons that album works is that it contains a few daring things to talk about, and you can kind of hear that it cost me to say them. I wasn’t coming from a position of “I know I’m right” — it was more like, “These are some things I have to say, and I don’t know what the consequences will be.”

I think that’s exactly right. There is some shocking insight in these songs, but they sound like they’re coming from someone who’s searching, not telling. And even a song like “Covert War,” which you singled out as coming from a very personal, singular experience, contains resonance for anyone who’s ever had a family. All of these songs contain some wonderful lines, but that one has two of my favorites — the one about being taught to kick under your breath instead of under the table, and the one you took from your father, about anger being like gasoline, a crude yet powerful fuel.

Yeah, he was a psychologist, and really addicted to anger — really afraid of his own. He’d bottle it up until it’d come screaming out with some weird alcohol thing. And it was weird that that quote about gasoline was his wisdom. Just about a year ago, I was talking to a friend of mine, who is another anger addict, and I quoted that line. He said, “Oh, that’s just crap. Just typical justification.” And I said, “Really?” [Laughs] It was interesting to see it in that light — over time, realizing that that wisdom has its limits too.

From the outside, this sounds like a song cycle about coming to terms with life as an adult —

Wow, that’s such a beautiful — you have gotten much more out of that record than I have. Truly cool.

Well, that’s the beauty of music, right? The gift you give your audience. [Laughs]

The wild part is that at that point, A&M knew whatever advice they had for me would probably do more harm than good. The success of How Did You Find Me Here was something they never anticipated, and they knew that radio was changing, and there was this weird opportunity for songs that would normally be too quirky and personal to be heard. So they didn’t give me any advice, which was kind of a mixed blessing because there were a lot of things about that record that could have used a mentor — you know, someone who could give me some perspective on what I was trying to say, and how I was almost saying it. So the parts of that record that always made me squirm were the parts where I was trying to be something I wasn’t yet — where the song was demanding that I step into a role that I couldn’t yet fill.

Which parts were those?

Well, even now, I’ve sort of obliterated the memory of those songs. Could you run down the track list?

Sure, absolutely.

It starts with “Burgundy Heart-Shaped Medallion,” and…then what?

“Farther to Fall.”

Oh, that’s pretty good. That’s innocent and sweet. Okay, what else?

“(You Were) Going Somewhere,” which is a Buddy Mondlock song.

That’s a beautiful one. Ben Wisch did so much good for that song, with the frame drum and everything, and I could believe in that lyric, so I sang it with ease, which was great.

“Wildberry Pie.”

“Wildberry Pie,” I think, could have been stripped down more. It was kind of too folk. The harmony was very lush — I was very lucky that Mary Chapin Carpenter came in to do that. It’s got a good sense of humor —

Yes, but it’s very smart. I think that’s one of the most clever songs about sex I’ve ever heard.

I’ve started playing that song again lately, and I’ve enjoyed it. It’s definitely different. My favorite person to play that for was a man who’d come to my concerts, and he was blind. He explained to me that it’s a blind man’s love song. [Laughter] He was like, “Every song is about lips and eyes or whatever, and I’ve never seen any of that stuff. But if you want to talk about scent…”

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/lWn4f1PUyiw" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

“Let Them In.”

That was great. I could rely on John Gorka’s awesome melodic sense, which he brought to that beautiful old poem.

“Distant Water,” which is another one that I think contains a lot of really wonderful imagery.

[Groans a little] “Distant Water” — oh God, that’s the one that kills me. You know, that’s one that I can — and I have — written many times in lots of different forms, and there are newer songs that sort of get that emotion better.

The weird thing about that song is that I was right in the midst of figuring out that the thing that could do me the most harm — the misunderstanding that could really wreck me — is this notion of romantic love as salvation. I just had a misguided notion about it, how it was going to transform me as a person. That’s a song that, if I’d had a little more time to live it and understand what I was singing about…when I hear it now, it sounds like me singing knowledge to me that I don’t understand. It’s like waking from a dream with wisdom that you can’t quite incorporate yet. The lessons were there, I just — it’s worse than “if I knew then what I know now,” because I was singing then what I know now, and I still didn’t know it.

“Top of the Roller Coaster.”

That one is a little embarrassing, because I think the arrangement is just a little too sweet. I don’t know how it could have been better, but it still feels like a swing and a miss.

I always liked that idea of turning 30 being like the top of the roller coaster, although looking back on a song about your 30th birthday must seem a little silly 20 years later.

Well, it was dealing with another huge issue for me — the question of whether it was too late to do the thing I came to do. To fulfill my destiny. I had this really overblown notion of my purpose on Earth being to get these songs out, and so that song does reflect really well that neurosis, but…yeah. There’s not a lot of reality there.

“Covert War.”

That’s a song that was written just for my parents, and I was only going to sing it for them, but it started a conversation that was really the beginning of a great change, and the more people I talked to, the more I heard it should go on the album. There was one person at A&M who thought it should have been the single. Everyone else shied away from it, but she was right, and if they had gone with that, it might have done something. Instead, there was all that wasted time with…oh, now I’m remembering the horrible song! [Laughter] Something about dancing!

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/GBVpOlIwHZs" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

“She’s Just Dancing.”

Oh, God!

I think you even had “She’s Just Dancing” t-shirts!

Blech. That’s a song that’s a great idea, and if a woman had performed it, it would have been cool. That’s an Ani DiFranco song, you know? With her baritone voice. And with me…just sad. Not good at all. Because there’s something about my sound that emotionally implies, “Gee, I really hope you like me.” And unfortunately, that’s the thing I’m making fun of in the song, and it works against itself. Ani, with a lot of anger behind her, could have done something with it. But instead, it starts doing all this moralizing and trying to pretend I’m not guilty.

It’s interesting to me that you say you’d only planned on playing “Covert War” for your parents, because it sounds like a lot of these songs are based on people and events in your life, and I wanted to ask you if you felt any sort of trepidation about putting them out there in public.

I wasn’t, but my mother was. [Laughter] She was offended. “Why does this have to be everybody’s business?”

We go from that into “Advertising Man.”

Yeah, again, a passive-agressive rant disguised as a happy-happy. I’m good at that!

And “Last Chance Waltz.”

Yeah, that’s sort of a confession of the under-appreciated high school wallflower. If it had been sung by someone like Gillian Welch, with a lot of pain in it, it could have been cool. I don’t know. Emotionally, it was really satisfying to write. I wrote it for one person, and sang it for that one person, and it was triumphant. It was huge, because it released all this weird residual longing, and made me sane. For my personal evolution, that song was crucial.

And yet when people request it now, it’s really hard for me to imagine a way to get back into it, because it’s just such a…it’s such a pitiful character, you know? The kind of person who is all disempowered and waiting on someone else to make them happy.

Musically, it always sounded to me like a cousin to “Language of the Heart.” I’ve wondered if it’s a sequel to that story.

Well, that’s actually the prequel. “Language of the Heart” was a newer song, and “Last Chance Waltz” was an older one that wasn’t good enough for the album before. It’s…the heart of songwriting, at this point, for me, is figuring out the most important lesson to learn so I can sing that every night. And what I mean by that is catching myself in my old mistakes that keep me fighting things I don’t need to fight.

That’s a song that my old friend Jamie would say sits in its own shit. I mean, it’s supposedly about how the healing has happened because she danced with me and all that, but it’s still kind of — the whole mood of it is so pleading. Won’t you please, you know, grant me a wisp of your beauty and I’ll be healed. And that was totally my world view.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/ickWCGc5qHw" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

We’ve talked about “She’s Just Dancing,” which comes next, and then we go into the beautiful “Chet Baker’s Unsung Swan Song.” And here’s one case where I think the added production benefits the song, because that flugelhorn is just lovely.

Yeah, I agree. And that’s a weird little — looking back on it, I realize that if we hadn’t been recording in New York, we could have just asked Herb Alpert to play that part, because he loved Chet Baker. That might have gotten the record a little extra attention. I don’t know.

And then, finally, “Mighty Ocean.”

That was written right when the record was almost done. The only regret I have about that one is that I wish I’d put the name of the actual restaurant where we met instead of just “Soho.” That would have granted it a little bit of quirkiness that — you know, the heart of it is that there’s mercy and reconciliation, and there’s some sort of wormhole through distance that allows us to acknowledge that we both tried, and we’re past all the distance that was between us. I wrote that in my first open tuning, so it has a real nostalgia for me.

When I look at all these songs, I think “Not bad.” I wonder why I was so unsatisfied with it at the time. I think maybe I realized I was sort of willfully sabotaging my career. For the right reasons.

What do you mean?

I mean that that record…especially opening with “Burgundy Heart-Shaped Medallion,” people would be going, “What the heck?”

There was a moment early on when I had the opportunity to go with a producer who was going to really give me a chance at radio, and I chose not to. I remember the thing that really changed my mind was that the producer said to me, “On the last album, we had a lot of women listening, and this time, we’re going to get everyone listening.” At the time, it felt to me like he was saying if I just cleaned up some of this wishy-washy emotional stuff, just get my tough thing on and learn how to strum loud and speak in generalities, I could make it happen. It sounded like death to me, so I chose to go with someone who was willing to let me do these confessional songs.

If someone was going to try and mold you in 1991, I’m surprised they wouldn’t just try and turn you into James Taylor.

There were definitely people who were voting for that at the label, and I think if I had sold more records with How Did You Find Me Here, they might have tried it. But they were kind of…I think they were distracted. They didn’t expect me to be their breadwinner.

There was something about my path that — there were things I needed to say, and I needed to say them in a way that was really clear. And not confrontational, but I was fighting a fight. I described it at the time as fighting the fight like Gandhi did — I wasn’t going to armor myself. I was fighting the fight against armor.

I’ve had people describe that record in particular as really…icky. Like, “Eww, why do I want to listen to his problems?” And it sits in the glovebox for a year or whatever until they’re going through something, and maybe it triggers a memory of a song, and they’re ready for it. You open up your heart and the song finds you there. It felt so important to me to be able to achieve that kind of closeness in music. And that kind of bravery. The kind of bravery I wished I had in my daily life. I was so shy and reserved — never had more than maybe two good friends — but I had this weird idea that music was going to be the place where I’d break that pattern and be unbelievably brave.

Dar Williams and I both had a friend, JaimÁ© Morton, who was a huge influence on our music. She was the one who started giving us the chance to believe that this kind of really confessional writing was somehow like fighting the good fight and changing the world — make it safe for quirky people to be themselves. Obviously, it wasn’t new, but this time around it felt…oh, I’m getting too abstract.

No, I understand what you’re saying, and it sends me back to what I was saying earlier about always thinking of Home Again as a very pure, uncluttered album — because at the time, in the context of what was popular, it really sounded that way. Now I can hear the machines, but during that era, it was artists like you and Dar and John Gorka who helped bring this style of writing back.

It’s so encouraging to me to hear what’s out there now. The Web has helped strip the formality out of music. In years past, if you wanted to write a song for the masses, you’d get rid of all the fingerprints, but that’s what makes a song really good. I think there’s a lot for me to learn from that record, and I’m getting a hint of that now in talking to you. Maybe what’s beautiful about it is not who I was, but who I was becoming, and maybe what I didn’t like about it is that I wasn’t there yet. But it shows me…like the math teacher says, “Show your work.” It definitely shows my work. It shows me grappling with issues and really doing the work that would eventually harvest into a life that felt beautiful.

Related articles

- Popdose Flashback ’91: Color Me Badd, “C.M.B.” (popdose.com)

- Popdose Flashback ’91: Marky Mark and the Funky Bunch, “Music For the People” (popdose.com)

- Popdose Flashback ’91: Squeeze, “Play” (popdose.com)

- Popdose Flashback ’91: Big Audio Dynamite II, “The Globe” (popdose.com)

Comments