I’ve always been a know-it-all. I was the kid who actually did read the encyclopedia for fun, and I carried my reputation as a fount of useless knowledge into adulthood and into the workplace. Break-room conversations would wind into arcane corners, until someone would say, ”Ask Jack — I’ll bet he knows.” And I’d find myself grappling with questions like why Easter moves around so much in the calendar, or why riders of show-horses wear those puffy trousers, or how a faulty car came to be called a ”lemon.”

I’ve been asked to end arguments, to settle wagers, or simply to satisfy someone’s curiosity. And I’ve always done it — sometimes willingly, sometimes not. For one glorious week, I found a way to make it pay, parlaying my mastery of trivia into a winning stint on Jeopardy! But my true calling has always been as the Office Explainer, telling you everything you could possibly need to know about the ephemera of art, science, and history — and slightly more than you might need, in fact, until it’s almost irritating.

The esteemed Jeff Giles, Generalissimo-for-Life of the Popdose Army, envisioned a way for me to harness this dubious gift for the benefit of our reading audience. That’s how PopSmarts came to be. Every other Thursday, I will use this space to go off on some topic in the arts and pop culture, dropping knowledge both utilitarian and useless, with no set brief, no word count, and no limits but my taste and your indulgence.

So stick around. You just might learn something…

The late filmmaker Stanley Kubrick has been much on my mind the last couple of weeks. The imagery of his films is now so ubiquitous as to become a part of the background noise of our culture, but for the past ten days or so I’ve been noticing it more than usual. A blogger I like posts a still from The Shining; an homage shows up on The Venture Brothers; a comics writer talks about the storyboards for Paths of Glory; and a trailer for a new feature documentary about Kubrick’s work hits the Web (more on that later).

The late filmmaker Stanley Kubrick has been much on my mind the last couple of weeks. The imagery of his films is now so ubiquitous as to become a part of the background noise of our culture, but for the past ten days or so I’ve been noticing it more than usual. A blogger I like posts a still from The Shining; an homage shows up on The Venture Brothers; a comics writer talks about the storyboards for Paths of Glory; and a trailer for a new feature documentary about Kubrick’s work hits the Web (more on that later).

So maybe I am primed to see the hand of the Master at work when I stumble across this news article about the right-wing think-tank FreedomWorks, on the Mother Jones website:

FreedomWorks Made Video of Fake Giant Panda Having Sex With Fake Hillary Clinton

Some FreedomWorks staffers worried last year about a promotional video created ahead of FreePAC, a FreedomWorks conference held on July 26, 2012… The short film hailing FreedomWorks was intended to play on the large video screens inside the arena.

In one segment of the film, according to a former official who saw it, Brandon is seen waking from a nap at his desk. In what appears to be a dream or a nightmare, he wanders down a hallway and spots a giant panda on its knees with its head in the lap of a seated Hillary Clinton and apparently performing oral sex on the then-secretary of state. Two female interns at FreedomWorks were recruited to play the panda and Clinton. One intern wore a Hillary Clinton mask. The other wore a giant panda suit that FreedomWorks had used at protests to denounce progressives as panderers…. Placing the panda in the video, a former FreedomWorks staffer says, was “an inside joke.”

My first thought after reading this, naturally enough, was Gosh, and people say that conservatives have no sense of humor. But my second thought was that the scene, as described, sounds an awful lot like a segment from Kubrick’s film The Shining.

That movie, adapted from Stephen King’s novel, concerns the family of an alcoholic writer (Jack Nicholson) who slowly loses his marbles while acting as the winter caretaker of a snowbound luxury hotel that may or may not be haunted. Near the end of the movie, the writer’s wife (Shelley Duvall) is fleeing through the hotel, which has become a gallery of horrors. The hotel’s transformation has the air of a hallucination, or a time-slip, or a ghostly visitation — some kind of altered reality, anyway — wherein she sees flashes of decadence and degradation from the hotel’s past. Among the phantasmagorical scenes she witnesses is a brief glimpse through a doorway of a sexual encounter between two men, one wearing a dog costume.

[youtube id=”7KwTqsnFyIM” width=”600″ height=”350″]I wondered aloud (via a comment I left on the Mother Jones article) whether the video’s creators might have been making an intentional reference to Kubrick film. The press has assumed that the ”inside joke” was political in nature; but what if it was a film-school joke — running a Kubrick image through a political-cartoonist sensibility?

Indelible images, after all, were Stanley Kubrick’s stock-in-trade. Although celebrated and derided in equal measure as a cold, cerebral formalist, Kubrick managed again and again to create pictures that resonate deeply in the irrational centers of our brains. Major Kong riding the bomb to glory, ape-men gamboling around a cryptic black slab, those creepy beckoning twins, hallways flooded with blood; these are images out of dreams, and they haunt us even though we cannot pin down their precise meanings.

Kubrick was able to sneak his weird tableaux into our psyches by wrapping them in the trappings of familiar genre movies. So many of his films have the surface elements of drive-in trash; the sword-and-sandal stabfest in Spartacus, juvenile delinquent panic with A Clockwork Orange, space opera in 2001, combat movies with Full Metal Jacket — even skin flicks, with the much-misunderstood Eyes Wide Shut. Kubrick applies his cool formalism to genres that are traditionally ”hot” — overtly emotional, sentimental, even sloppy — setting up the genre expectations, and then transcending them.

Or perhaps subverting is a better word. There’s always a satirical edge at play with Kubrick, and even his grimmest films function as black-comic deconstructions of their respective tropes. Sometimes he seems to respond to a particular film. Dr. Strangelove can be seen as a comedic rebuttal of the Cold War thriller Fail-Safe (although the two were being made at approximately the same time, Fail-Safe was based on a well-known novel). My favorite Kubrick, Barry Lyndon, reads as a disgusted response to the rakish ribaldry of Tom Jones. Even Lolita, if you squint at it right, comes off as a twisted take on the lush domestic melodramas of Douglas Sirk.

Kubrick, in other words, was making movies about movies — not in the glib, self-satisfied manner of a Quentin Tarantino, where simply quoting from an old flick substitutes for actual insight, but in a rigorous, inquisitive manner. Kubrick was intent on questioning the founding principles of these genres, and teasing new shades of meaning out of familiar setups. Tarantino’s a fan, but Kubrick — Kubrick was a critic.

So you can watch The Shining, for instance, as if it were ”just” a horror movie, and your senses will accept it as such. But all the while it’s working on you, laying mind-eggs in your brain, with images and ideas that interrogate the assumptions of traditional horror movies — starting with the exact nature of the evil infesting the Overlook Hotel, and whether it’s coming at the characters, or from them.

So you can watch The Shining, for instance, as if it were ”just” a horror movie, and your senses will accept it as such. But all the while it’s working on you, laying mind-eggs in your brain, with images and ideas that interrogate the assumptions of traditional horror movies — starting with the exact nature of the evil infesting the Overlook Hotel, and whether it’s coming at the characters, or from them.

A lot of audiences (and even some critics) fail to see this combination of puckish wit and moral seriousness that runs through Kubrick’s work. They see only the theorist, the technician, the intellectual. And so they distrust him. Kubrick made popular, successful films, and has a firm place in the pantheon of English-language cinema, but it’s hard to think of another major director who is regarded with such suspicion.

Indeed, there’s a swirl of honest-to-god conspiracy theories that surround Kubrick — some of which came up in the Mother Jones thread linked above. To be fair, it’s my own damned fault for commenting there in the first place; Mother Jones comment threads inevitably devolve into batshit-crazy political name-calling on both sides.

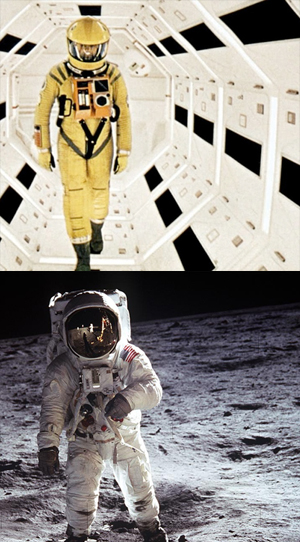

My innocent comment about Kubrick, though, set off something staggering in its derangement. Kubrick was called a self-hating Jew, and it was mentioned — not as an assertion, but in passing, as an article of faith — that the Moon landings were a gigantic hoax perpetrated by the US government with Kubrick’s help (!), and that by enabling such blatant fakery Kubrick himself was morally culpable for all subsequent phony videos, including the FreedomWorks video itself. Because apparently, before Kubrick, the camera never lied. Oh, and apparently the airplanes flying into the Twin towers on 9/11 were a hoax created for video, too, thousands of eyewitness accounts notwithstanding. (That’s Kubrick’s fault, too, even though he didn’t directly have a hand in creating those videos, having died in 1999.)

Of course, Kubrick conspiracies thrive even outside the fever swamps of the paranoid fringe. Take a look at the trailer for Room 237, an upcoming doc about The Shining:

[youtube id=”khPPlvMnaV0″ width=”600″ height=”350″]In Room 237, director Rodney Ascher talks to various cultural critics, film historians, and obsessive fans, each of whom offers a different exegesis of The Shining. One sees it as an elaborate allegory for the genocide of Native Americans; another, as a Holocaust parable; yet another, as Kubrick’s own coded confession for his part in having faked the Moon landings.

Now, any or all of these might be true — except the Moon-landing thing, which is flagrant bullshit — but notice the tone here. Usually when an artist creates a work that can be read on multiple levels, it’s an occasion for praise; the work is called deep, rich, rewarding, profound. But Kubrick’s (possible) schema of multiple meanings for The Shining is presented as a deception, a cryptogram, a conspiracy. Another director might be praised for the subtlety of his themes; Kubrick is accused of hiding the film’s ”true” meaning. (As if a film can only mean one thing.) And all the time he’s laughing up his sleeve at us dummies, still grappling to figure out his riddles.

The underlying assumption of public anti-intellectualism is that a man who knows things must of necessity have no beliefs, no core values; that he is a nihilist, and so cannot be trusted. He is too clever by half. He thinks he’s smarter than us, and is not above simply messing with our heads for his own amusement. That’s why so many people distrust Kubrick, distrust his motives, are convinced there’s something he’s not telling the audience. To put it bluntly, we are afraid that he is trying to put one over on us.

That’s the problem with know-it-alls. Or maybe it’s not: I could just be fucking with you.

Comments