Last week saw the anniversary of one of the most horrific events in American history, the shootings of four unarmed college students by National Guardsmen on the campus of Ohio’s Kent State University. Four casualties may not sound like much of a body count, in a world where collapsing factories kill 900 workers and suicide bombers can wreak havoc in crowded public spaces. Hell, as I write this article, at least 35 people are dead in India after their bus crashed through a guard rail and into a gorge along the Beas River. Thirty-five lives snuffed out, and each of them precious; 35 people, each of whom had hopes and dreams for the future, hopes just as valid as those of Sandy Scheur, or Allison Krause, or Jeff Miller, or Bill Schroeder.

But the Kent State massacre was a uniquely traumatizing incident in the social history of the United States. Three days of ugly antiwar demonstrations had escalated into full-scale rioting, with wholesale property damage culminating the torching of the University’s ROTC building. Some student protestors actively hindered the local fire brigade as they attempted to quell the blaze. The governor of Ohio authorized the deployment of the National Guard; pounding his fists, and with voice raised in anger, he denounced the protestors as ”worse than the Brownshirts.” On May 4, 1970, two companies of National Guardsmen moved in on an assembly of students, to enforce an order to disperse. The Guard fired volleys of tear gas; the students responded with rocks. After intermittent skirmishes, a sergeant of the Guard discharged his sidearm — and for thirteen seconds, the grounds in front of Taylor Hall became a free-fire zone. Sixty-seven rounds of ammunition were fired, resulting in four people killed and nine wounded; one would be paralyzed for life. For the first time since the Civil War, an arm of the US government had systematically employed deadly force against its own citizens.

The incident elicited worldwide shock and horror. The most public and enduring response came from Neil Young; the blistering protest song ”Ohio” was written and recorded (by Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young) within weeks of the shootings. From its opening moments — a stumbling, snarling electric guitar riff clawed out by Young on his Les Paul — to the guttural wails of Stephen Stills and David Crosby at the fade-out, ”Ohio” finds and sustains its mood of righteous outrage. Rush-released as a single for June, ”Ohio” knocked CSNY’s own gentle ”Teach Your Children” off the pop charts, and became an anti-anthem, a soundtrack for a national mood of fear and loathing.

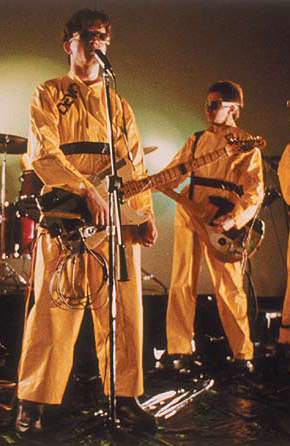

[youtube id=”YnOoNM0U6oc” width=”600″ height=”350″]But to whom do the events of Kent State truly belong? Certainly the anti-war Left — the remnants of the hippie scene — adopted the memory of Kent as a rallying cause, and ”Ohio” as a mourning dirge for an activist movement that was watching its dreams of peaceful social change go down in a hail of bullets. When punk-rock satirists Devo covered ”Ohio” years later — in a version released on the cheekily-titled multi-artist compilation When Pigs Fly: Songs You Never Thought You’d Hear (2002) — it was tempting to hear their take as a rebuke of hippie idealism and naÁ¯vetÁ©. And there are surely black-comic elements to it, from the drumbeat made up of sampled gunshots to the cartoonish, ”Summertime Blues”-style voice booming, ”Send those hippies straight to Hell!”

The truth, though, is more complex. The divide between the hippie and punk scenes is often assumed to be primarily generational — that is, to correspond with demographic age cohorts — with hippies belonging to the Baby Boom, while punks arose from the leading edge of Generation X. Notionally, this cast the punks as the bratty younger brothers of the hippies, naturally rejecting the values of their elders. (Rather conveniently, this schema also allowed the hippies to dismiss the criticism leveled at them by the punks: After all, what did they know? They weren’t there, man.)

In fact, there was considerable overlap between the late hippie and early punk scenes.

And in fact, Devo were there, man.

Jerry Casale — bass player, songwriter, videographer and ”chief strategist” for Devo, the man largely responsible for the band’s look, philosophy, and presentation — was born and raised in Kent. While attending the state university there, he met up with Akron natives Mark Mothersbaugh and Bob Lewis, who shared his interest in music, surrealist art, and poststructuralist philosophy; they would later form the nucleus of Devo’s first incarnation. Casale also befriended Jeffrey Miller and Allison Krause. Casale was out on the university common with Krause on May 4, 1970, and was standing near her when a single M1 bullet, fired from 330 feet away, passed through her left arm and into her torso, where it fragmented on impact. Within hours, she was dead of massive internal injuries.

And in an instant, Jerry Casale had stopped being a hippie. And the ”devolution“ concept that he and his bandmates had been toying with — the jokey notion that mankind was regressing into something primitive, tribal and savage — suddenly seemed all too plausible.

[youtube id=”70WWqy0iSC8″ width=”600″ height=”350”]Coming at the dawn of the 1970s, the Kent shootings seemed to signal the end of the utopian social project of the 60s. With the Vietnam War grinding on and American society fragmenting along generational and socioeconomic lines, the national mood grew increasingly apocalyptic. The implicit social contract had been shredded. In America and around the world, splinters of the youth protest movement were hardening and radicalizing, presaging a shift in tactics into domestic terrorism or outright gangsterism. Doomsday cults were bunkering down, stockpiling weapons and poisons, hatching plans to murder public officials and foment revolutions. Cities seemed ungovernable. Mismanagement and criminality at the highest levels of government would eventually bring down the presidency. So bitterly divided was this country that there was genuine and widespread doubt that the democratic experiment itself could last through the decade. America had peaked, it seemed, and there was nowhere to go but down. Devolution.

And just as the ethos of the Sixties Left had a fraught, fraternal relationship with those of punk — as bloodied idealism either rushed to sell out or gave way to frustrated nihilism — so Devo had a complicated relationship with the song ”Ohio,” and with Neil Young personally. Casale loathed ”Ohio” upon its initial release, feeling that the song was exploitive and that Young et al. were ”rich hippies… making money off of something horrible.”

As the years passed and Devo began to gain notoriety, though, Young was an early champion of the group, one of the few among rock’s old guard who seemed to ”get” what they were about. They bonded over an interest in film and visual art, and even collaborated on Young’s 1982 film Human Highway.

There was still the matter of that song to be addressed, however. For Neil Young, ”Ohio” was an emblematic story, and its players were abstractions. Young’s existential musing — “What if you knew her, and found her dead on the ground?” — was, for Casale, anything but a rhetorical question. And so Devo’s cover finds room in its dark, discordant synth squiggles for both a newly-written second verse — self-deprecatingly characterizing themselves and their late friends as “factory workers dodging Vietnam” — and an extraordinary breakdown, as the music falls away and a big echoing voice spells out the title — but way in back, at the edge of hearing, there’s another voice intoning a memento mori:

O…

(Jeffrey)

H…

(Allison)

I…

(William)

O…

(Sandra)

…And ”Ohio” stops being an object lesson of Hippies vs. The Man, and the human tragedy that it always was becomes staggeringly clear. Four dead: not symbols, not martyrs, not abstractions. People. With identities of their own, outside of any morality play you may care to construct around them. With names.

And if it took doom-haunted smart-alecks in flowerpot hats to bring that all back home, such are the vagaries of culture. Because cultural movements, too, are made up of people. And people have stories that will surprise you every time.

Comments