In the summer of 1958, three of the biggest stars pop music would ever see were born — Prince, Madonna and Michael Jackson. All three are, for what it’s worth, enshrined in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. And in the past two years, the Popdose Guide has covered the output of two of those artists. So, in honor of her 53rd birthday (which she’s spending in the Hamptons with her two youngest kids and her 24-year-old boyfriend), Madonna acolytes Robin Monica Alexander and Kelly Stitzel decided it was high time Her Madgesty got her own entry. And so we bring you the Popdose Guide to Madonna.

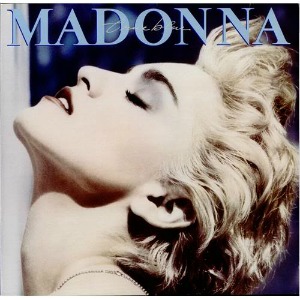

Madonna (1983)

A lot of brain-dead stuff has been written about Madonna over the years. Might good old-fashioned sexism be part of the problem? Madonna is particularly susceptible to sexist criticism because, like fellow superstar and gay icon Barbra Streisand, she exerts an unusual amount of control over her work for someone who was only supposed to be a “girl singer.” For example, on Madonna, her 1983 debut album, she wrote five of the eight tracks, including its biggest hit, “Lucky Star.” However, in later years she remarked that it wasn’t the album she hoped it would be, due to, you know, her total inexperience in the record business. It’s cool, Madonna…you did okay.

Madonna is the love child of the New York dance club scene and pure American girly pop. The vocals — endlessly criticized as weak, squeaky, or immature — are exactly what the material needs: it sounds like the girl next door is singing to you about her guy problems. The girl next door has a little bit of an identity crisis, in that one moment she wants nothing more than to party the night away under a disco ball (“Everybody”), or, uh, get laid (“Physical Attraction,” a track that sounds like a leftover from 1978 — in a good way), and the next she’s sweetly imploring her macho boyfriend to trust in her love (“Borderline”), but that’s the dichotomy that made Madonna distinctive. For every song (and video) that cast her as sexually loose or aggressive, there was another that portrayed her as just a charming girl from the neighborhood. “Lucky Star” manages to do both at once: its suggestive beat and Madonna’s vocal bring the sex while the lyrics — “Star light, star bright/First star I see tonight” — evoke a fairy-tale innocence (that is, until that chorus: “Shine your heavenly body tonight”).

Madonna is the love child of the New York dance club scene and pure American girly pop. The vocals — endlessly criticized as weak, squeaky, or immature — are exactly what the material needs: it sounds like the girl next door is singing to you about her guy problems. The girl next door has a little bit of an identity crisis, in that one moment she wants nothing more than to party the night away under a disco ball (“Everybody”), or, uh, get laid (“Physical Attraction,” a track that sounds like a leftover from 1978 — in a good way), and the next she’s sweetly imploring her macho boyfriend to trust in her love (“Borderline”), but that’s the dichotomy that made Madonna distinctive. For every song (and video) that cast her as sexually loose or aggressive, there was another that portrayed her as just a charming girl from the neighborhood. “Lucky Star” manages to do both at once: its suggestive beat and Madonna’s vocal bring the sex while the lyrics — “Star light, star bright/First star I see tonight” — evoke a fairy-tale innocence (that is, until that chorus: “Shine your heavenly body tonight”).

Madonna was not an instant hit, but its popularity built gradually between the summer of 1983 and the spring of the following year, aided by videos which allowed Madonna to show off the East Village ragamuffin chic that had made her a well-known character around NYC. (They also revealed that she was white, which took some early fans by surprise.) Its singles were more successful — where else? — on the Club chart and the dance floor. Madonna did most of her live performance dates to support the album in clubs. It wasn’t until 1985 when she launched a full-scale concert tour, in support of…

Like a Virgin (1984)

At first glance, it appears as if Madonna exerted even less creative control over her second album than over the first: this time around, she shares her songwriting duties (on four of the five tracks credited to her), and most of the record’s biggest hits were penned by others. But appearances can be deceiving. Every song was handpicked by the diva-in-training, as was the album’s producer, Nile Rodgers, who had just performed a successful (if not universally acclaimed) sound makeover for David Bowie on Let’s Dance. Additionally, Like a Virgin marked the beginning of a long and fruitful collaboration with Stephen Bray, whom Madonna had known back home in Michigan and whom she had persuaded to come to New York some years earlier, when she was, of all things, the drummer for the band The Breakfast Club.

It seems impossible that a song called “Like a Virgin” was out there waiting to be recorded by a girl named Madonna, but stranger things have happened in show business. That saucy tune, her first number one and the first of four Top 10 hits from the album, provides early evidence of Madonna as a provocateur and sly cultural commentator. Musically, Like a Virgin seems a bit of hodgepodge, careening from the novelty-record cuteness of “Material Girl” to the, frankly, ill-advised R&B cover “Love Don’t Live Here Anymore” to the faux-girl group sweetness of “Shoo-Bee-Doo.” However, when the record works, it works like gangbusters: Madonna may have wanted to get away from the disco and prove she could be a bona fide pop star, but the tracks that find a beat and don’t let up — the title song, “Angel,” and “Dress You Up” — turn out to be the most enduring and the least dated.

If ever a performer understood the power of “synergy,” it’s Madonna. In addition to her 1985 “Virgin Tour” (another clever play on words), she promoted the album, and herself, by appearing the same year in Desperately Seeking Susan, in which her character wears pretty much the exact same outfits Madonna wore in her videos. She also did a cameo as a club singer in Vision Quest, and “Crazy for You” and “Gambler,” the songs she performs in the film, appeared on its soundtrack. Meanwhile, “Into the Groove,” which is heard in Desperately Seeking but is not on the soundtrack (seriously, people?), was also generating a lot of attention. “Crazy for You” became Madonna’s second number one, while “Into the Groove,” ineligible for Pop chart consideration because it was not released as a 7″ single, was swiftly added to the 1985 reissue of Like a Virgin. This saturation of the airwaves could have backfired, but instead, it silenced all talk of Madonna as a flash in the pan, created the subculture of “Madonna-wannabes,” and, preposterously, landed “Dress You Up” on Tipper Gore’s list of bad, nasty music, alongside “Darling Nikki” and “Eat Me Alive.”

True Blue (1986)

While filming the video for ”Material Girl,” Madonna began dating actor Sean Penn and the pair married on her birthday in 1985. Madonna’s unabashed love for her new husband inspired her to start writing songs for her third album, Live to Tell, which would eventually be titled True Blue. Lyrically and musically more mature and focused than her first two albums, True Blue was not only a valentine to Penn, but also Madonna’s declaration of intent to be taken seriously as a singer, songwriter and entertainer and proved, once and for all, that she was force to be reckoned with in the world of pop music.

Possibly her least overtly sexual album, on True Blue Madonna instead chose to focus on love and romance. Listening to this album is like reading a friend’s diary in which she ruminates about boys she has crushes on (”Jimmy Jimmy”), her romances, both good (”True Blue”) and challenging (”Open Your Heart”), past mistakes she’s made (”Papa Don’t Preach”), disappointments she’s had (”Live to Tell”), dealing with work stresses (”Where’s the Party”), and places she loves and wishes she could go back to (”La Isla Bonita”). Perhaps the only entry worth skipping in this diary is the one where she talks about war and poverty and espouses the idea that love can solve all the world’s problems (”Love Makes the World Go Round.”)

Possibly her least overtly sexual album, on True Blue Madonna instead chose to focus on love and romance. Listening to this album is like reading a friend’s diary in which she ruminates about boys she has crushes on (”Jimmy Jimmy”), her romances, both good (”True Blue”) and challenging (”Open Your Heart”), past mistakes she’s made (”Papa Don’t Preach”), disappointments she’s had (”Live to Tell”), dealing with work stresses (”Where’s the Party”), and places she loves and wishes she could go back to (”La Isla Bonita”). Perhaps the only entry worth skipping in this diary is the one where she talks about war and poverty and espouses the idea that love can solve all the world’s problems (”Love Makes the World Go Round.”)

True Blue was a huge commercial success for Madonna, soaring to the top of the charts in an unprecedented 28 countries. Five singles were released, three of which — ”Live to Tell,” ”Papa Don’t Preach” and”Open Your Heart” — hit number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. The other two singles, ”True Blue” and ”La Isla Bonita,” were also top-five hits. To support this album and the soundtrack to her film Who’s That Girl?, Madonna embarked on her first world tour in 1987. The “Who’s That Girl World Tour” was a giant success, earning $25 million and making it the second-highest grossing tour by a female artist that year.

Like a Prayer (1989)

If True Blue was the “I love Sean Penn” album, Like a Prayer was the “I lost Sean Penn” album. The most obvious reference to the breakup of the tempestuous marriage is “Till Death Do Us Part,” while the instant anthem “Express Yourself” asks, “Do you believe in love?” but insists that it can survive only if women begin demanding the respect they deserve (sexually and otherwise). All the turmoil in the singer’s life obviously caused her to get introspective and spiritual. The religious undertones implicit in the work of a woman named Madonna become overtones, as the record begins with the gospel-esque, Jesus-freaky title track and ends with “Act of Contrition.” More popery asserts itself on “Pray for Spanish Eyes,” which continues the Latin-American theme Madonna began to explore in “La Isla Bonita” and “Who’s That Girl” (Quien es esa niÁ±a?), and the haunting “Oh Father,” which might be about abuse at the hands of one’s parent or one’s priest. And the latter song, along with “Promise to Try” (a lament for a lost loved one) and “Keep It Together” (a paean to the bonds of family), excavate Madonna’s complicated backstory: losing her mother at five years old, being raised by a strict and religious father, and growing up with seven siblings in a working-class home.

If True Blue was the “I love Sean Penn” album, Like a Prayer was the “I lost Sean Penn” album. The most obvious reference to the breakup of the tempestuous marriage is “Till Death Do Us Part,” while the instant anthem “Express Yourself” asks, “Do you believe in love?” but insists that it can survive only if women begin demanding the respect they deserve (sexually and otherwise). All the turmoil in the singer’s life obviously caused her to get introspective and spiritual. The religious undertones implicit in the work of a woman named Madonna become overtones, as the record begins with the gospel-esque, Jesus-freaky title track and ends with “Act of Contrition.” More popery asserts itself on “Pray for Spanish Eyes,” which continues the Latin-American theme Madonna began to explore in “La Isla Bonita” and “Who’s That Girl” (Quien es esa niÁ±a?), and the haunting “Oh Father,” which might be about abuse at the hands of one’s parent or one’s priest. And the latter song, along with “Promise to Try” (a lament for a lost loved one) and “Keep It Together” (a paean to the bonds of family), excavate Madonna’s complicated backstory: losing her mother at five years old, being raised by a strict and religious father, and growing up with seven siblings in a working-class home.

Not sure if all of these themes were really deeply probed by the record-buying public; mostly, they were focused on the fact that Madonna had once again made an album that was equal parts sexy, ballsy, danceable, and, of course, irresistible (“Cherish,” possibly the most idiotic song she has ever recorded, is impossible not to sing along to). Her grip on the reins of her career had never been tighter: she is credited as co-writer and co-producer on every single track — including “Love Song,” a weird duet with Prince that’s reliably funky but obviously didn’t get the best effort of either performer. Having passed through the career stages of starlet and diva, Like a Prayer vaulted Madonna to an even higher status: pop music icon.

Erotica (1992)

After the success of Like a Prayer, the mostly unsucessful throw-back sound of I’m Breathless, the hugely important “Blond Ambition Tour” that supported those albums, the release of the provocative behind-the-scenes tour documentary Truth or Dare, and the banned-from-MTV video for ”Justify My Love,” which appeared on her first greatest hits compilation, Madonna’s fans waited breathlessly to see what she would come up with next. They didn’t have to wait long because in October of 1992, she released her two most controversial, sexually-charged projects: the Sex book and the Erotica album.

Consisting of sexually explicit images photographed by Steven Meisel, Sex caused a very negative backlash from both the media and general public, even distancing some of her fans, who thought she might have gone a little too far this time (though not too far, it seems, since Sex sold 1.5 million copies in just a few days). Simultaneously came the release of Erotica, her fifth studio album and the first on her new vanity label, Maverick Records. Erotica extended the sexually explicit themes of Sex, becoming her first album to feature a Parental Advisory sticker.

Not only were the lyrics on Erotica controversial, but so was the change in musical direction Madonna took on the album. Co-produced with Shep Pettibone and Andre Bettis, she explored the sounds of house, disco, New Jack Swing, reggae and jazz, in addition to the dance pop that she was known for.

Though the songs explore intimacy, sex and romance, most of them are cold and calculated, rather than warm and sensual, particularly the title track, in which Madonna takes on a dominatrix persona. ”Where Life Begins” is an obvious ode to cunnilingus and is the most overtly sexual song on the album, which is saying a lot. With its breathy vocals, it’s meant to be sexy, but the fact that fact that it refers to the vag as ”where all life begins” is clinical, un-sexy and off-putting.

There are some fun moments on the album, like the disco romp ”Deeper and Deeper,” one of the best tracks on the record, the reggae-infused ”Why’s It So Hard” and the house-heavy cover of ”Fever.” Interestingly, Erotica’s ballads provide some of its strongest material. ”Bad Girl” tells the tale of a woman who indulges in too many vices and pays the price for emotionally destroying herself. ”Rain” is a striking love song reminiscent of earlier ballads like ”Live to Tell” and features some of Madonna’s strongest vocals to date. And ”In This Life” is a poignant memorial for a friend Madonna lost to AIDS that laments how the disease took her friend at a young age and in which she expresses hope that a cure will be found in her lifetime. Had this been the final track of the record, instead of the boring and unnecessary ”Secret Garden,” Erotica would’ve been that much more powerful.

Erotica was not as commercially successful as Madonna’s previous albums, though it received quite a bit of critical acclaim. It is probably her most underrated album, its strength and importance getting lost under all the controversy that surrounded it.

Bedtime Stories (1994)

After the backlash to the explicit sexuality of Erotica and the Sex book, Madonna decided to tone things down a little bit and take a softer approach with her sixth album, Bedtime Stories. Where Erotica approached sexuality in a cold, domineering fashion, Bedtime Stories is warmer and more sensuous, even down to the cover art and promotional photographs.

For the first time since her collaboration with Chic’s Nile Rodgers on Like a Virgin, Madonna chose to work with established producers, collaborating with Dallas Austin, Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds, Dave ”Jam” Hall and Nellee Hooper, all of whom had experience in producing R&B artists. The resulting sound on Bedtime Stories was more mainstream and radio-friendly. Many of the songs feature R&B samples and Me’Shell Ndegeocello and Edmonds provide backing vocals on a few tracks.

Lyrically, the songs on Bedtime Stories are more confessional and intimate than those on Erotica. Songs like ”Secret,” ”Inside of Me,” ”Forbidden Love” and ”I’d Rather Be Your Lover” explore themes of love and romance without being overtly sexual. ”Love Tried to Welcome Me” and the album’s biggest hit, the ballad ”Take a Bow,” both lament heartbreak and loneliness. ”Survival” and ”Human Nature” are two of the most confrontational songs on the album, in which Madonna speaks directly to her critics. Lyrics like ”I’ll never be an angel/I’ll never be a saint it’s true” and ”I’m not sorry/I’m not your bitch/Don’t hang your shit on me” find her unapologetic about her life and the artistic choices she’s made, with ”Human Nature” specifically addressing the controversy surrounding Sex and Erotica.

Lyrically, the songs on Bedtime Stories are more confessional and intimate than those on Erotica. Songs like ”Secret,” ”Inside of Me,” ”Forbidden Love” and ”I’d Rather Be Your Lover” explore themes of love and romance without being overtly sexual. ”Love Tried to Welcome Me” and the album’s biggest hit, the ballad ”Take a Bow,” both lament heartbreak and loneliness. ”Survival” and ”Human Nature” are two of the most confrontational songs on the album, in which Madonna speaks directly to her critics. Lyrics like ”I’ll never be an angel/I’ll never be a saint it’s true” and ”I’m not sorry/I’m not your bitch/Don’t hang your shit on me” find her unapologetic about her life and the artistic choices she’s made, with ”Human Nature” specifically addressing the controversy surrounding Sex and Erotica.

Interestingly, it’s the title track that is the most different from anything else on the record. Co-written by BjÁ¶rk, Hooper and Marius DeVries, ”Bedtime Story” forgoes the R&B grooves prominent on the rest of the album for a more electronic, trip-hop sound, which can also be found, to a lesser extent, on its lead-in, ”Sanctuary.” Madonna would explore this electronic path further in her future work with producers William Orbit and Mirwais AhmadzaÁ¯.

A quiet commercial success, Bedtime Stories peaked at number three on the Billboard Hot 100 album chart and produced four moderately successful singles, with ”Take a Bow” being the only number one. It was not accompanied by a tour and most of its songs have never been performed live — only ”Secret” and ”Human Nature” have seen proper live performances.

Later this week, look for Part 2 of the Popdose Guide to Madonna…in which the “Material Girl” becomes “Madge,” releases five more studio albums, and goes to number one a few more times.

Related articles

- Happy Birthday, Madonna! (newsroom.mtv.com)

- Madonna Turns 53 Today: See Her Transformation! (news.instyle.com)

- Wandering the Aisles: Going Gaga for Madonna (popdose.com)

Comments