Call them “comics” only if you need to. It’s the shorthand we’ve used for about a century for stories told through sequential art, but not all “comics” are alike. So it is with Greg Ruth, the acclaimed creator of The Lost Boy, co-creator of Indeh with Ethan Hawke, and highly prolific artist. His preferred mode: moody black and white, highly detailed, with each panel opening up to a world of its own. Ruth is embarking on a new project with Hawke now, and his 52 Weeks Project of art based on a single source of inspiration is neck deep in the White Lodge at Twin Peaks. Popdose spoke with Ruth on a number of subjects, which was more difficult than it should have been since we can hardly turn away from his artwork.

Call them “comics” only if you need to. It’s the shorthand we’ve used for about a century for stories told through sequential art, but not all “comics” are alike. So it is with Greg Ruth, the acclaimed creator of The Lost Boy, co-creator of Indeh with Ethan Hawke, and highly prolific artist. His preferred mode: moody black and white, highly detailed, with each panel opening up to a world of its own. Ruth is embarking on a new project with Hawke now, and his 52 Weeks Project of art based on a single source of inspiration is neck deep in the White Lodge at Twin Peaks. Popdose spoke with Ruth on a number of subjects, which was more difficult than it should have been since we can hardly turn away from his artwork.

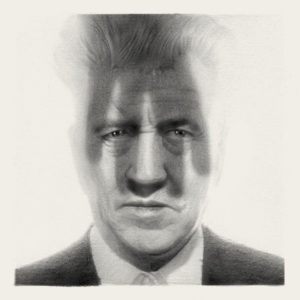

Your 52 Weeks Project this time is focused on Twin Peaks. First, could you explain a bit what the 52 Weeks Project is, and second, what drew you to Twin Peaks as the subject, aside from the revival at Showtime?

Well, I started the self-assigned weekly drawing thing, The 52 Weeks Project, as a kind of codified act of playing hooky a few years ago mainly as a way to keep the art-making fresh and interesting for me when it had become a full time 9-5 rigorous job, and was starting to feel like a grind. So it was a way for me to start off the work week with desert, rather than Brussels sprouts, if you know what I mean. It really did the trick and then of course ended up being such an essential and integral part of work… what was really supposed to be a lark, became a children’s book I did with President Obama, at least a dozen cover jobs, a music video gig, work for Criterion, and a bucket of other companies, and a weekly source of added income and a successfully overfunded hardcover book we did through Kickstarter.

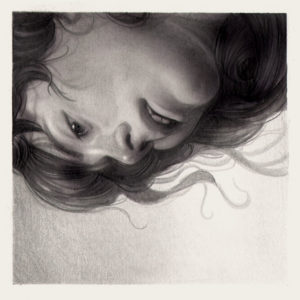

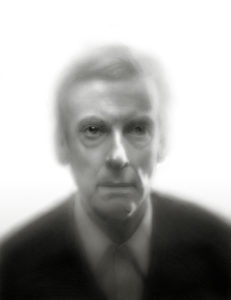

Well, I started the self-assigned weekly drawing thing, The 52 Weeks Project, as a kind of codified act of playing hooky a few years ago mainly as a way to keep the art-making fresh and interesting for me when it had become a full time 9-5 rigorous job, and was starting to feel like a grind. So it was a way for me to start off the work week with desert, rather than Brussels sprouts, if you know what I mean. It really did the trick and then of course ended up being such an essential and integral part of work… what was really supposed to be a lark, became a children’s book I did with President Obama, at least a dozen cover jobs, a music video gig, work for Criterion, and a bucket of other companies, and a weekly source of added income and a successfully overfunded hardcover book we did through Kickstarter. I guess what drew me to the subject of Twin Peaks was simply an enthusiasm for the material- it began airing back when I was a freshman/sophomore at Pratt, and was a total phenomenon. It was by miles, the most artful and insane piece of tv we’d seen since The Prisoner, and none of us could believe it was on network tv. (For you kids out there, back in those days we still really only had three or four stations to chose from. Yes, cable had it’s thing, but they weren’t making original content yet). It was amazing to see how this campus literally shut down for a couple of hours as everyone scrambled around whoever had a tv in their dorm room for us to crowd around to watch an episode. The visual language of the show was so rich and became so iconic, as did the characters and so it was a natural thing to want to do portraits of each of them for the original series. The Return is a whole different animal in many ways, and inspired an unexpected reviving of The White Lodge drawings entirely by accident. I had done this one drawing of Cooper footing in the box that Jeff Lemire grabbed, and I honestly thought that would be it. But each week I’d come away wanting to do another, and so without planning, I had a whole new series rolling out- I think I’ve done ten now to date.

I guess what drew me to the subject of Twin Peaks was simply an enthusiasm for the material- it began airing back when I was a freshman/sophomore at Pratt, and was a total phenomenon. It was by miles, the most artful and insane piece of tv we’d seen since The Prisoner, and none of us could believe it was on network tv. (For you kids out there, back in those days we still really only had three or four stations to chose from. Yes, cable had it’s thing, but they weren’t making original content yet). It was amazing to see how this campus literally shut down for a couple of hours as everyone scrambled around whoever had a tv in their dorm room for us to crowd around to watch an episode. The visual language of the show was so rich and became so iconic, as did the characters and so it was a natural thing to want to do portraits of each of them for the original series. The Return is a whole different animal in many ways, and inspired an unexpected reviving of The White Lodge drawings entirely by accident. I had done this one drawing of Cooper footing in the box that Jeff Lemire grabbed, and I honestly thought that would be it. But each week I’d come away wanting to do another, and so without planning, I had a whole new series rolling out- I think I’ve done ten now to date.

Unless my information’s incorrect, I hear you might be planning a new project with Ethan Hawke. You and he collaborated on the graphic novel Indeh. How did that pairing come together?

Unless my information’s incorrect, I hear you might be planning a new project with Ethan Hawke. You and he collaborated on the graphic novel Indeh. How did that pairing come together?

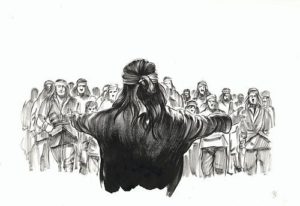

Ethan saw Conan: Born on the Battlefield in Forbidden Planet in NYC, was struggling with how to tell this story of the Apaches he’s been working on for years, and had an a-ha moment I think in looking at the book. He reached out, we had lunch- I always like to talk about how I didn’t intend or expect to be doing this with him, but really just thought we’d have lunch, it’d be a nice moment, snd then we’d get back to our lives, etc…. Well that one hour meeting turned into a 3+ hour meeting of the minds and I walked out of there committed to the project. We got on like a house on fire- I think as a surprise to is both. We were and still are like two kids in a sandbox together and all these years later, he’s like a brother to me. I personally, had not planned to partner up like this- I had just come off of The Lost Boy, and was eager to continue assuming the lonely life of a creator-owned comics guy… he’s such a brilliant story guy. We’re both share a real passion for reading, watching, editing and constructing these stories, digesting them, parsing them out, etc. It’s likely a terrible bore for others around us. But it’s been a total partnership- unlike most projects like this where some celebrity drops a story off at the editor’s desk and then returns to his thing, Indeh was a hand in hand walk until the very last moment. I never expected to have so much fun working with another before; it’s a very intimate and vulnerable thing, and this new one even more so.

We fully intended to follow Indeh up with its second part, largely on the basis that we supremely desired to tell Lozen’s story that got cut from the first book, but while we were doing the book tour for Indeh, we started writing a new father/son coming of age crime story that grabbed us fully and now that’s what we’re doing next, again for our amazing editor, Gretchen Young at Grand Central/Hachette Books. It’s very reflective of our parallel lives as fathers to 15 year old boys, autobiographical in terms of it’s setting and time in Texas where we were both born, and is a great bit scary for us which is what attracts us to it so strongly. We could have never made it without having first proven the level of trust we instilled in the process of Indeh, because it’s so damned personal and close to the bone. We’re writing the script now. It’s called Meadowlark.

We fully intended to follow Indeh up with its second part, largely on the basis that we supremely desired to tell Lozen’s story that got cut from the first book, but while we were doing the book tour for Indeh, we started writing a new father/son coming of age crime story that grabbed us fully and now that’s what we’re doing next, again for our amazing editor, Gretchen Young at Grand Central/Hachette Books. It’s very reflective of our parallel lives as fathers to 15 year old boys, autobiographical in terms of it’s setting and time in Texas where we were both born, and is a great bit scary for us which is what attracts us to it so strongly. We could have never made it without having first proven the level of trust we instilled in the process of Indeh, because it’s so damned personal and close to the bone. We’re writing the script now. It’s called Meadowlark.  I’ve seen a few things that discussed your art process and it is both fascinating and a little scary. You don’t pencil sketch first — instead, you go straight to the paper with ink and brush. That seems like there would be a lot of opportunities for things to go wrong, but it clearly works for you. How did you come to adopt this regimen?

I’ve seen a few things that discussed your art process and it is both fascinating and a little scary. You don’t pencil sketch first — instead, you go straight to the paper with ink and brush. That seems like there would be a lot of opportunities for things to go wrong, but it clearly works for you. How did you come to adopt this regimen?

Things go wrong all the time with the sumi, but you just wad up the paper and throw it over your shoulder to do it again. It’s different each and every time, and I’ve done innumerable cover paintings with it, two graphic novels, both Indeh and The Lost Boy, and a video for Prince with it. The 52 Weeks Project itself was largely a sumi thing until very recently.

The other thing is that (also, unless I’m mistaken), the panels for your stories are done full-size, and then scanned and placed onto a page digitally. That sounds like a really interesting way to get maximum detail into each panel. How do you go about coordinating the pages to work out the compositions?

The other thing is that (also, unless I’m mistaken), the panels for your stories are done full-size, and then scanned and placed onto a page digitally. That sounds like a really interesting way to get maximum detail into each panel. How do you go about coordinating the pages to work out the compositions?

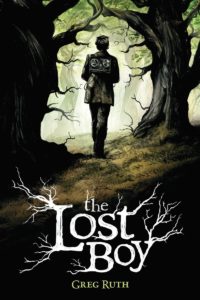

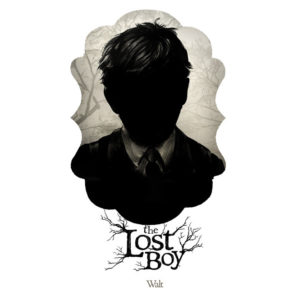

The Lost Boy seems like a movie waiting to happen (or, as the current case may be, three movies). What was the impetus to write it?

The Lost Boy seems like a movie waiting to happen (or, as the current case may be, three movies). What was the impetus to write it? (I wrote a pair of long form articles on the subject called Why Horror Is Good For You, And Even Better For Your Kids originally for Muddy Colors, and then again for Tor.com.)

(I wrote a pair of long form articles on the subject called Why Horror Is Good For You, And Even Better For Your Kids originally for Muddy Colors, and then again for Tor.com.)

While currently there’s just the first book out there, I did draft and map out the full trilogy all the way to the end. The second book following in part Walt’s post-villain life as an outcast living alone in the Kingdom, and the aftermath of the events at Harker’s Drop, particularly what really came back with them looking like Tabitha, and book three, which ties the entire secret history of the town and it’s relationship with the Kingdom culminating in this terrifically massive confrontation with these ten story tall Willow Tree women. Let’s just say whatever weirdo notes were sounded in the first one gets ramped up by a factor of ten.

These last two books, if I get the opportunity to do them, are really one big story split in half, and structured in a way with the first so if they were all put together they would read rather seamlessly as a whole epic.

The Scholastic Books of my day are much different than the ones of today, post-Twilight. When you delivered The Lost Boy to them, what was the reaction? While the story is meant for younger readers, it is a dark kind of story.

The Scholastic Books of my day are much different than the ones of today, post-Twilight. When you delivered The Lost Boy to them, what was the reaction? While the story is meant for younger readers, it is a dark kind of story.

But it brought me my first NY Times bestseller listing, and really changed a lot for me in a million different ways. It is a dark and challenging complex story, but I think kids are such sophisticated readers- especially these days- and are rarely rewarded with such material, I just couldn’t resist putting my money where my mouth is. Scary stories aren’t for every kid no doubt, but for those who really love them, it’s a special kind of honor to please them. The support, the letters and cosplay and all the support from Scholastic has been such an incredible affirmation. Kid’s lit is still an area I am really devoted to and look forward to returning to after Meadowlark– which, despite centering around a kid, is in no way whatsoever meant or intended for children — it’s a rough edged frenetic noir piece that literally pulls no punches.

But it brought me my first NY Times bestseller listing, and really changed a lot for me in a million different ways. It is a dark and challenging complex story, but I think kids are such sophisticated readers- especially these days- and are rarely rewarded with such material, I just couldn’t resist putting my money where my mouth is. Scary stories aren’t for every kid no doubt, but for those who really love them, it’s a special kind of honor to please them. The support, the letters and cosplay and all the support from Scholastic has been such an incredible affirmation. Kid’s lit is still an area I am really devoted to and look forward to returning to after Meadowlark– which, despite centering around a kid, is in no way whatsoever meant or intended for children — it’s a rough edged frenetic noir piece that literally pulls no punches.

You’ve said previously that you were never really into comic books per se. You didn’t like the open-ended, soap opera nature of them. But Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns changed that. The idea that you could tell a single story that starts and conclusively finishes got your attention. What did that change in your mindset?

So The Dark Knight Returns, Mai The Psychic Girl, Watchmen, etc. were pure revelations for me, and helped reintroduce me to the medium of comics in a way that lives on today. The way the market changed, the old comic shop market collapsing and the reduction of Marvel and DC into essentially being IP farms for their parent corporation’s film divisions really afforded and opportunity for the book world to take the medium under its wing and start to finally, after generations of insane self-immolation, take the medium seriously and start growing up and catching up to where it has been driven in other cultures like Europe, Japan and Latin America; where it has such a vibrant and diverse playground to run about in.

So The Dark Knight Returns, Mai The Psychic Girl, Watchmen, etc. were pure revelations for me, and helped reintroduce me to the medium of comics in a way that lives on today. The way the market changed, the old comic shop market collapsing and the reduction of Marvel and DC into essentially being IP farms for their parent corporation’s film divisions really afforded and opportunity for the book world to take the medium under its wing and start to finally, after generations of insane self-immolation, take the medium seriously and start growing up and catching up to where it has been driven in other cultures like Europe, Japan and Latin America; where it has such a vibrant and diverse playground to run about in.I could never have sold Indeh or even The Lost Boy, or Meadowlark in the old comics industry dominated world, and we’d have never seen such legitimately literary masterpieces come like Persepolis, Essex County, March, Boxers and Saints, Smile, or the dozen other excellent genre busting stories we get to have now. While the mid 1980’s-early 90’s were a true renaissance period for comics, and an incredible time to come up in, there has been no better period in American history to be making graphic novels than right now. Forget the superhero stuff, the myriad of other environs has never been richer. Indeh‘s been out just a year now and has already been translated into, I think, six different languages. It’s an amazing time.

Could you go into the materials you use?

Could you go into the materials you use?

Comments