Not every creative professional can claim to have badgered Ringo Starr on network television, ushered the popular SCTV characters Bob & Doug McKenzie onto the big screen, and directed a nail-biting cult classic of ’80s cinema before having his first published short story, “Rubiaux Rising,” chosen by The Lovely Bones author Alice Sebold for inclusion in The Best American Short Stories 2009. But as Steve De Jarnatt writes in “Mulligan,” another one of his acclaimed stories, “You can’t change your mind so easy if you keep yourself in motion.”

In 1988, when I was still in grade school, I fell head over heels for Strange Brew (1983), starring Rick Moranis and Dave Thomas as the lovable Canadian “hosers” Bob & Doug. A year later I read a capsule review of a new suspense thriller called Miracle Mile and recognized the name of its writer-director from the screenplay credits of the earlier film. Skip 20 years ahead and his name popped up once again, this time in the latest edition of The Best American Short Stories. I thought, Could this be the same guy?

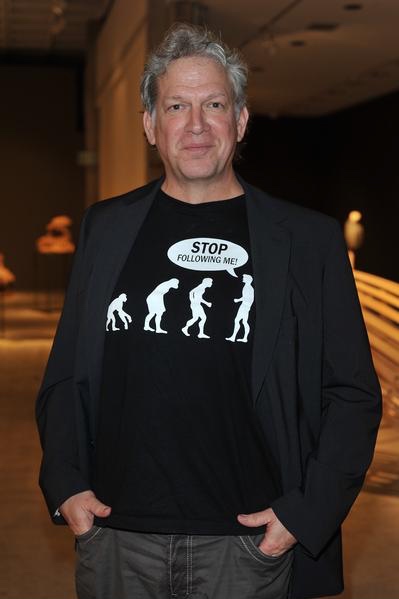

De Jarnatt at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery on January 9, 2011, for a series of short-fiction readings, including “Rubiaux Rising” (photo credit: Richard Shotwell)

Four years after that I noticed we had a mutual Facebook friend, novelist and short-story writer Christine Sneed (Little Known Facts, Portraits of a Few of the People I’ve Made Cry). After congratulating them both on the news that they’d made it into the “Notables” section of The Best American Short Stories 2013 — Sneed for “The Finest Medical Attention,” De Jarnatt for “Mulligan” — she suggested that I “friend” him on Facebook (“You should; he’s very nice”), at which point I decided to figure out how De Jarnatt got from point A, cowriter of a movie based on a comedy sketch, to point B, respected author of short fiction. It’s not a career path you read about often, especially if it also involves directing a pair of feature films, Cherry 2000 (1988) and the aforementioned Miracle Mile (1989), that are discovered by new fans every year.

Woven throughout De Jarnatt’s work is a creeping sense of oblivion, whether the cause is natural (a hurricane in “Rubiaux Rising,” a freak hailstorm in “Mulligan,” all kinds of earth-science wonders and horrors in the short story “Her Great Blue”), political (the threat of nuclear war in Miracle Mile), or financial (“the age of automation and unemployment, the rise of the machine and the fall of man,” as one character puts it, in Strange Brew; the plight of the protagonists in “Her Great Blue” that leads them deep into the Atlantic; the plight of Earl the farmer in the upcoming “Harmony Arm” that leads him to accept a buyout). And sometimes oblivion has already settled in and is now just a fact of life, as in the postapocalyptic southwest of Cherry 2000 and even Bob & Doug’s home movie “The Mutants of 2051 A.D.”

De Jarnatt always manages to find the humor and humanity in oblivion, however, sometimes through bizarre conceits — I doubt I’ll ever read a better, more tender love story between a woman and a whale than “Her Great Blue” — and sometimes through mash-ups of opposing ideas — the boy-meets-girl setup of Miracle Mile is certainly one of the most clever uses of misdirection that I’ve seen in a movie. (One of the ancillary thrills of reading his short stories is witnessing a former filmmaker no longer bound by budgetary considerations. His imagination can take us to any location, interior or exterior, it wants.)

The language in De Jarnatt’s short stories is a reminder of what author Gary Lutz told creative-writing students at Columbia University in 2008: “I favored books that you could open to any page and find in every paragraph sentences that had been worked and reworked until their forms and contours and their organizations of sound had about them an air of having been foreordained — as if this combination of words could not be improved upon and had finished readying itself for infinity.” Because if Steve De Jarnatt’s body of work has taught me anything, it’s that infinity is coming for all of us, one way or another.

The following interview took place on November 14 of last year because I was hoping to celebrate Strange Brew‘s 30th anniversary by the end of 2013. I didn’t estimate how long it would take to transcribe a 90-minute interview, though, so here we are 13 months later, just in time to close out Miracle Mile‘s 25th anniversary. Where there’s a will, there’s a way to manipulate the numbers.

Robert Cass: So “Rubiaux Rising” really was the first piece of fiction you sent out in hopes of being published?

Steve De Jarnatt: Yeah. I went to Antioch L.A.’s low-residency MFA program for creative writing, and just before I graduated I sent “Rubiaux” out and got a few rejections. Then Santa Monica Review picked it up and that was a big thrill, and then a year later there was an e-mail to Andrew Tonkovich, the editor [at SMR], saying, “Hey, congratulations, and does Steve know?” So it was kind of an indirect thing, and it didn’t register till later in the day or even the next day: Oh, I’m going to be in that book that I have on my shelf. Initially I just thought, Alice Sebold likes my story — that’s cool.

I wouldn’t have any lit career without her. I got to meet her in New York with Heidi Pitlor, the ongoing editor of Best American Short Stories, who pulled “Rubiaux” from the massive pile she reads every year. That will always be the height of any literary kudos I ever get, and I’d be remiss in not thanking them again emphatically. I still can’t believe I got to be in that book. The astounding thing to me is how many really top-quality writers there are out there, and you’re lucky to get in any magazine. All that stuff’s a crapshoot, to get in the big compilations.

RC: What got you interested in writing fiction?

SDJ: Well, I got to start at the top in the film world and squander my good fortune and hype and buzz and work my way to the bottom after 27 years. It was just too hard to get work, and I just decided to find something I could do, you know, mainly for the muse, the pure creative thing — not for the money, of course — and decided to get a master’s degree. Not that that’s worth anything …

RC: (laughs) I just got one last year.

SDJ: It’s funny. I actually didn’t turn in my final college paperwork till about six months before I tried to get a master’s degree. I never actually graduated from college, I found out, but no one ever asked the whole time I was in Hollywood. But, you know, I had to get that degree in order to get the master’s.

It was a great experience. I read fiction, but I’m a very slow reader; I’m not really well read. I mean, I certainly voraciously read short stories, but I always used to flip through the pages of novels and go, “Where’s the plot?” because I’d be adapting something for a screenplay. Now I read totally different: I care about the sentences and the art and the craft and all that. I have to reread everything again, I guess.

RC: I’m a very slow reader too, which is why I haven’t finished “Her Great Blue” yet.

SDJ: Oh yeah, it’s pretty long.

RC: I am going to finish it; I just ran out of time before the interview, unfortunately. But you do have a gift. “Rubiaux Rising” and “Mulligan” — it’s really good stuff.

SDJ: Those two are probably my best, and that whale one [“Her Great Blue”] is out there. I have a bunch of others, but I’m trying to go for ones that sort of fit together and, hopefully, send a collection out soon.

RC: Yeah, I was going to ask if you were trying to put together a collection of stories.

SDJ: I have a lot of stories — in my mind I like collections where the stories are different — but it seems like publishers want them aligned by theme or something, so I’m also trying to at least have eight to ten that fit together, with weather and animals and true events and things like that.

SDJ: I have a lot of stories — in my mind I like collections where the stories are different — but it seems like publishers want them aligned by theme or something, so I’m also trying to at least have eight to ten that fit together, with weather and animals and true events and things like that.

RC: I could be reading too much into it, but in “Mulligan” there’s some apocalyptic imagery with the hailstorm: “Devil smoke and mad flickering climb heavenward as more explosions nearly blind the eye.” I’m not saying that “Mulligan” is one of your “apocalyptic” stories, but—

SDJ: You read whatever I put in the essay in the back of Best American Short Stories 2009?

RC: Yeah, let me get that quote …

SDJ: Sometimes authors aren’t even aware, but yeah, I like to just put the reader and my characters through the ringer somehow.

RC: You wrote that you have “a tendency to be drawn to primal survival stories.” And that you wanted to give Rubiaux the fewest options — basically, to put him up against the wall. Or the ceiling, as it were, in “Rubiaux Rising.”

SDJ: (laughs) That’s good. I like that.

RC: To just give him food, air, water, and then have him work his way out surrounded by the Noah’s Ark-like menagerie, which is very nice.

SDJ: I’m almost sort of consciously putting a lot of animals in stuff now, and I don’t know if it’s a good idea, ultimately, but a couple of agents had said, “Well, you gotta link your stories a little bit by theme.” I may decide to go against that grain at some point, but that’s what I’m heading for now.

RC: Has that changed in recent years? I’m not that well read myself, but one of the things that got me into wanting to try to write fiction was Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, and I don’t think of those stories as being thematically linked, exactly, except that he’s talking about blue-collar characters most of the time — and, well, love.

SDJ: He’s so influential. By the time I went to Antioch, one of my teachers, Rob Roberge, had said there was a time when everybody was writing “a Raymond Carver story.” Even if they grew up in Manhattan and were rich, they were writing about a steeplejack. And, you know, Donald Barthelme was very influential on another level. I think probably Denis Johnson was “the guy” when I was there. Might still be, but who knows.

[Thematic linkage] is more of a marketing thing, which I don’t care about, but you gotta play ball a little bit. I’ll be happy if I just get a decent university press to put out a collection. You try to be one of the ones that gets published back east, but it’s a long shot.RC: Well, I wish you the best of luck with it, because these are good stories. Elmore Leonard had some line about how people don’t usually skip over dialogue, but they can skip over description. But you write description really well.

SDJ: I’m aware of my excess. In fact with “Her Great Blue” the editors at New England Review went, “We know this is excessive,” but they gave me no notes. (laughs) I’m used to Hollywood, where you do a page-one rewrite. I kept suggesting cuts, but they said, “You know, we’re just gonna embrace it. It’s unfettered imagination.”

That doesn’t happen all the time, of course. I also get nice notes from big magazines or just the cold little rejection slip. It’s just like in Hollywood: you have to go through all these readers who are there to say no, and the people in the slush pile, even though I got a couple nice things published, you could knock my stuff out of the box really easy because I’m not a minimalist, realistic writer. But it’s what I’m gonna be doing, I guess — the other stuff doesn’t come out of me.

In the attic Rubiaux watches light pour in — dancing dust around, slow and celestial like the Milky Way. His ears improve with a crack-jaw yawn. What’s that high-pitched rushing? Those low knocking sounds like bowling heard outside the alley. And that slow, mean rumble. What is coming this way?

A shock wave hits the house like a dozen Peterbilts crashing one after another into the frame. Beams groan, the whole foundation nearly quaking off its shoulders, nails and screws strain to hold their grip, eeking like mice as wood and metal mad grapple to hold their forced embrace.

A new light shines at the far window, painting the ceiling with golden ripples. Reflection. Water. Water is coming. Water is here.

—from “Rubiaux Rising,” Santa Monica Review, 2008

RC: I’m curious, because from what I can find on the Internet, were you 18 years old when you appeared in Ringo Starr’s 1978 TV special?

SDJ: (laughs) Wikipedia says I was born in 1960? Yeah, sure! Please don’t correct that, but it’s off by, you know, a ways.

RC: Okay, so that’s not accurate. Because that would mean you made the short film “Tarzana” when you were 12 years old.

SDJ: Yeah, I did — in 35-millimeter black and white.

RC: But not when you were 12 years old.

SDJ: Yeah, no. A few years later.

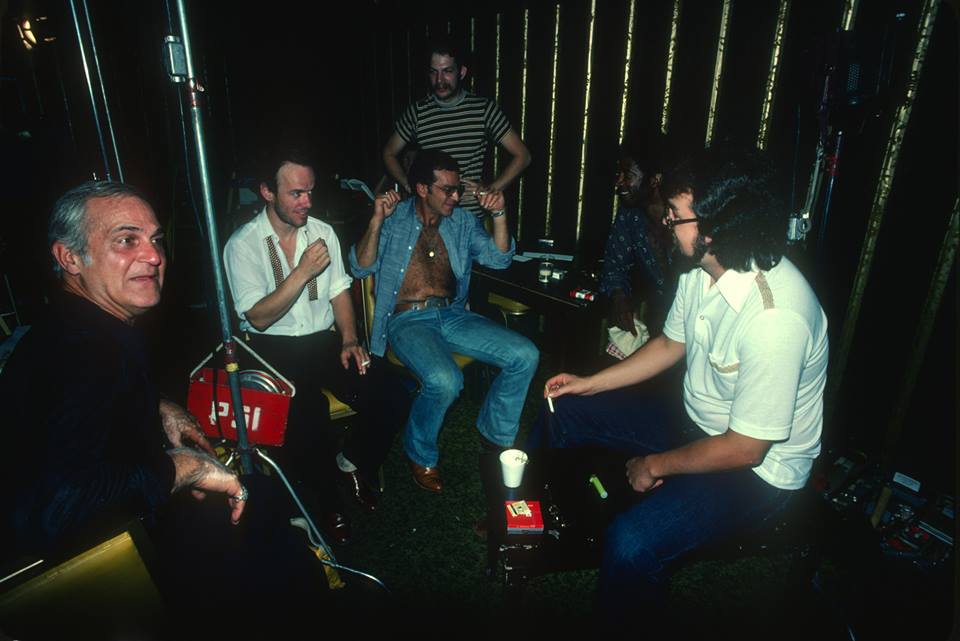

De Jarnatt (standing) on the set of “Tarzana” with, among others, jazz musicians Pete Candoli (far left) and Freddie Redd (second from right) and actor Michael C. Gwynne (second from left) (photo credit: Peter Lonsdale)

RC: Is it correct that you wrote Miracle Mile around 1978?

SDJ: Yeah. I went to the American Film Institute with a pretty exceptional class, really: John McTiernan [Die Hard, The Hunt for Red October]; Ed Zwick and Marshall Herskovitz [The Last Samurai, the TV series Thirtysomething]; Stuart Cornfeld, who produced The Elephant Man and is now Ben Stiller’s producer; George Lucas’s producer, Rick McCallum [the three Star Wars prequels]; Ron Underwood, who did City Slickers; Carel Struycken [Twin Peaks, Lurch in the Addams Family movies] — I gave him his first acting job, in “Tarzana”; and Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, an important New York photographer now.

Marty Brest [Beverly Hills Cop, Scent of a Woman] and Amy Heckerling [Fast Times at Ridgemont High, Look Who’s Talking] were in the class just ahead of me, and I followed Marty and Amy into Hollywood — actually, before most of the rest of my class — with “Tarzana.” I had dropped out of the school, but somehow over two years I shot four times and made this black-and-white detective-movie film noir pastiche. It did the trick, and people offered me features off it. (laughs) But I turned them down and squandered my opportunities in order to make Miracle Mile.

RC: Was Strange Brew one of the jobs you took while you waited for a studio to let you direct Miracle Mile?

SDJ: Yeah. Joel Silver [producer of Die Hard, Lethal Weapon, The Matrix, etc.] actually put the whole thing together. Dave and Rick were really depressed because John Belushi had just died and they had to go back on SCTV, which was this incredible show. And Joel Silver went, “There’s gotta be a Bob & Doug movie, there’s gotta be a Bob & Doug movie!”

So he sent them a couple scripts of mine. They liked this logging comedy that I wrote and Miracle Mile, which of course doesn’t have anything to do with Bob & Doug-style comedy, but they liked the writing. So all of a sudden I’m staying in the Park Plaza in Toronto for weeks, and we’re bandying stuff around while they’re going back on the show. And then it was sort of like, MGM has to have a script in two weeks.

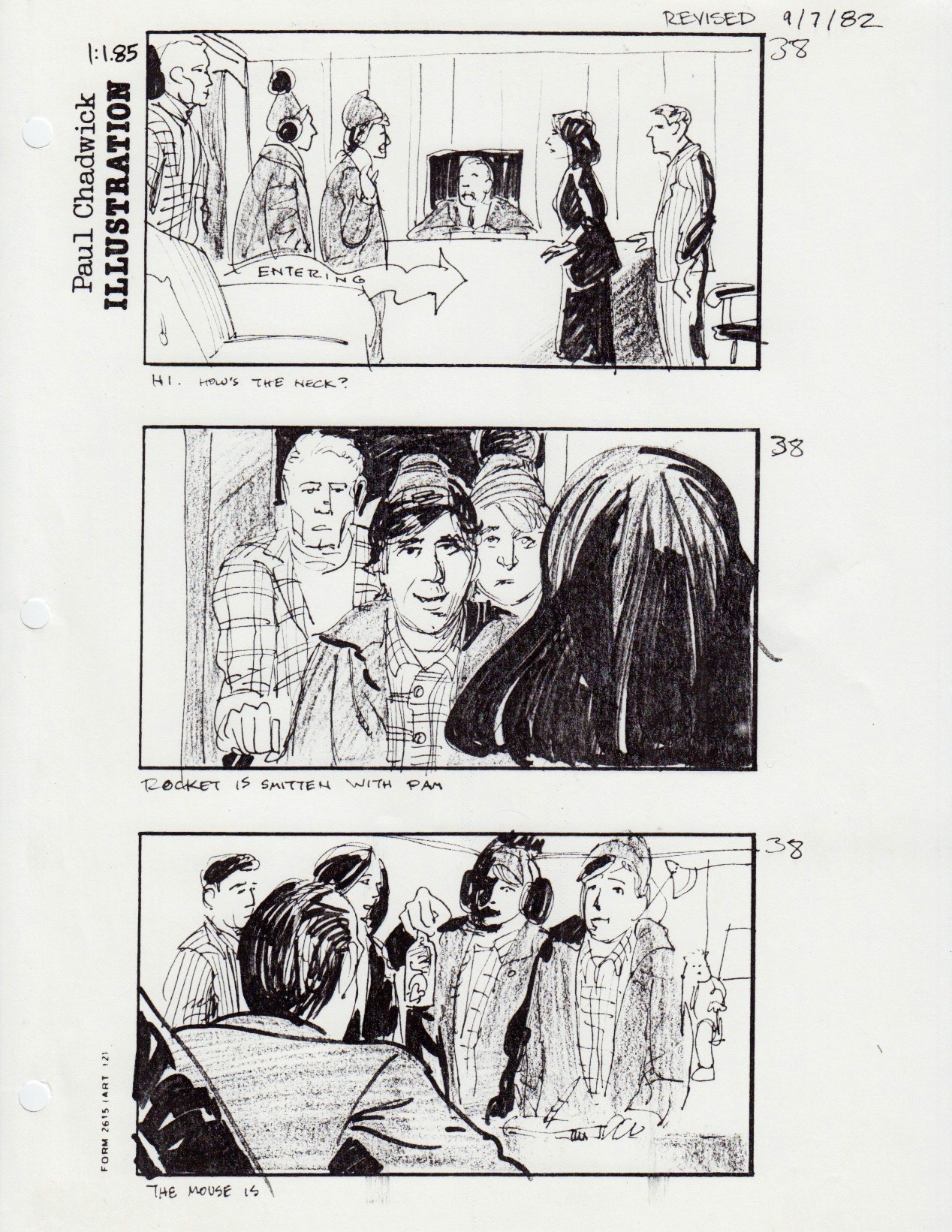

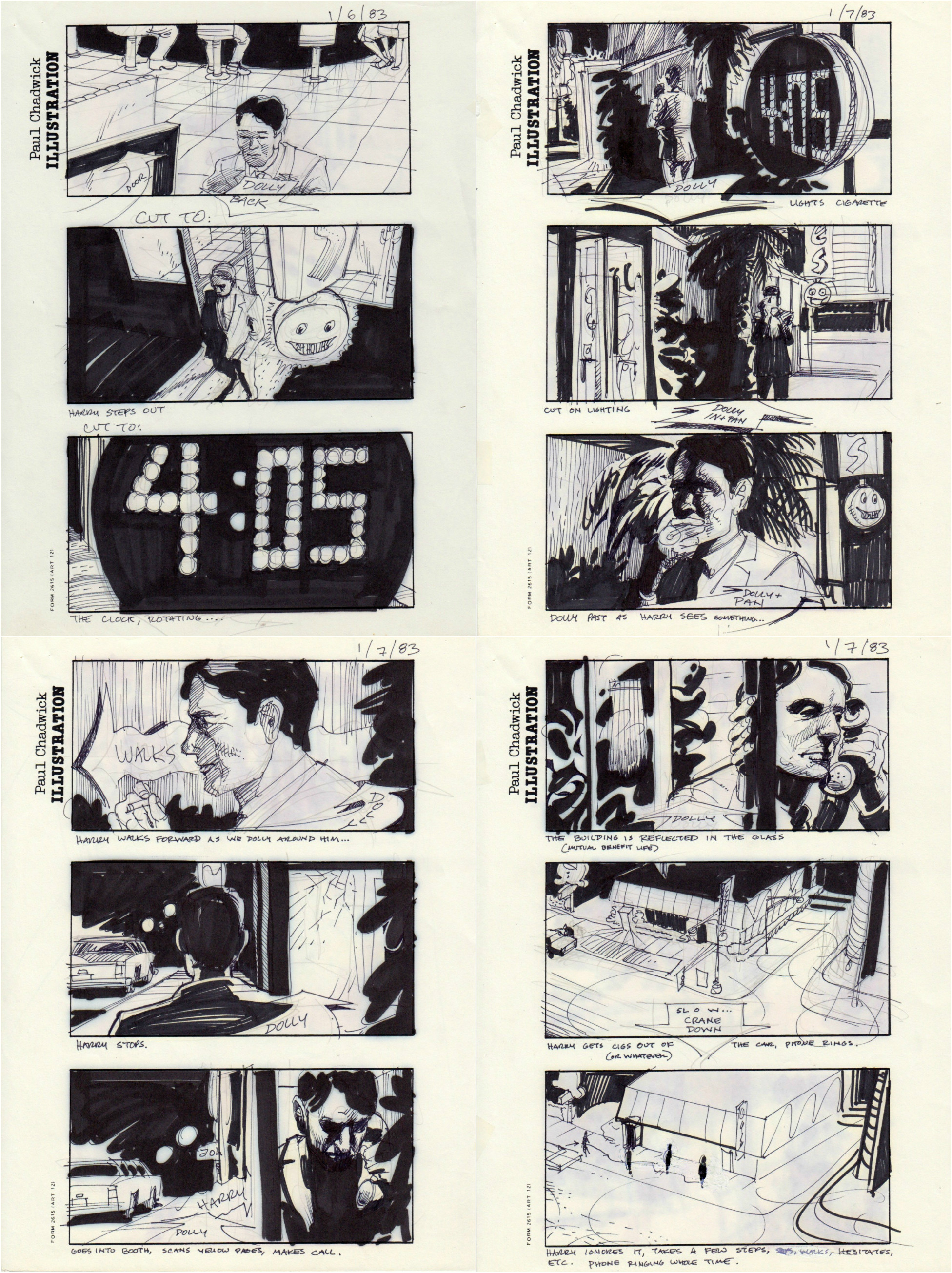

one of Paul Chadwick’s storyboards for Strange Brew (1983)

We came up with Hamlet in a brewery: Elsinore Brewery, the ghost in the machine, “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Hosers, Eh?” And I wrote a script in ten days. And, at least storywise, it’s exactly the story that was filmed. Dave and Rick improvised a lot, so the dialogue changed considerably, but I just found the script in my storage, and it’s storyboarded because I was going to direct it — I was hired to direct it, actually, but it went [into production] as a Canadian movie with a point system. [In other words, in order for MGM to receive a Canadian tax credit, Strange Brew‘s cast and crew had to be primarily natives of the Great White North. —Ed.]

RC: I guess it’s somehow fitting that you weren’t allowed to direct since you aren’t Canadian, because those characters came about because of “Canadian content” rules, apparently.

SDJ: I mean, I think Dave and Rick were going to direct it anyway, but I was gonna be the official director. [Run Ronnie Run, the 2003 feature film spun off from HBO’s Mr. Show With Bob and David, was produced under a similar arrangement between writer-actors Bob Odenkirk and David Cross and director Troy Miller. —Ed.]

I hired Blade Runner‘s art director, David L. Snyder, and we were gonna do a fairly ambitious thing with duplicating The Shining‘s trailer, but with beer instead of blood. It was always gonna be a cheap movie, but I remember the line producer, Jack Grossberg, who had done early Woody Allen movies, said, “It doesn’t matter what it looks like, it’s just gotta be funny.” MGM wouldn’t up the budget to do the ambitious stuff, and as it turned out, the directors needed to be Canadian. I got paid to not direct Strange Brew, and I gave all my money to Warner Bros. to buy Miracle Mile back [after selling the script in the late ’70s].

RC: There’s an interview with Dave Thomas from 2000 in which he says he gave you the basic Hamlet structure, but is that not how you remember it?

SDJ: All I remember is Dave and Rick were so crazed on SCTV, and maybe we had some structure that we worked out together, and then I wrote a draft and MGM liked it. I can’t even really remember other than if I hadn’t finished that draft in ten days there wouldn’t have been a deal for a movie.

At the time Joel Silver was doing, um … what was the big Eddie Murphy movie?

RC: 48 Hrs.?

SDJ: 48 Hrs.! So this is how Dave and Rick were in those days: they said, “Joel, you have to leave 48 Hrs. and come up to Canada or we won’t give you a credit.” And they didn’t give him a credit! And he didn’t leave 48 Hrs., or else he would never have become Joel Silver. He sort of forgave them, I guess, but they actually demanded he do that, and he didn’t do it.

RC: That’s wild, because I first saw SCTV when I was 13 or so, and Rick Moranis would play a character named Larry Seigel, but I didn’t find out until much later that that was his impression of Joel Silver.

SDJ: Oh yeah! He kicks his legs together and he goes, “Get my mom on the phone! … Mom, I can’t talk to you!”

RC: Did Moranis and Thomas rewrite the beginning of the movie [a meta-joke opening sequence that involves Leo the Lion, Bob & Doug’s amateur film “The Mutants of 2051 A.D.,” and a jar full of moths being opened in a crowded movie theater]? Is Dave Thomas correct about that?

SDJ: I remember I put the moth thing in there. And I put the mouse-in-the-bottle thing in there, which was from the show. When I was in Toronto getting ready to make the movie, we thought we were going to have this huge budget and kind of go crazy — you know, the way Blues Brothers went crazy.

I must say, Dave and Rick are both hilarious, and we got along great up until, like, the week before it became a Canadian movie. It was like, “Okay, well, at least I have a contract and you can pay me to go away,” and I wished them well. I think I actually said, “You guys need me, because otherwise you’re gonna end up hating each other. You could’ve fought with me.” And that’s what I heard happened — I think Dave and Rick ended up becoming estranged. Dave had to do all the editing and finish up the film while Rick was off doing Streets of Fire.

RC: Also produced by Joel Silver.

SDJ: It was for the best, but it did lead me to turn down the first Pee-wee Herman movie [Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, 1985], because I was offered that right afterward, and it was like, I didn’t want to go do another comedy skit. I took myself way too seriously, and some guy named Tim Burton took it on, and I don’t know whatever happened to him, but he owes it all to me. (laughs)

RC: He probably wouldn’t want to hear this, but that’s still my favorite Tim Burton movie.

SDJ: I give him all the credit. The script was kind of funny, but he made that work; I would not have been a good person for that. David Snyder ended up doing the art direction, and Paul Chadwick, the storyboard artist, I hired him for Miracle Mile [after working with him on Strange Brew]. He does a Dark Horse comic now called Concrete that has a pretty big following. [De Jarnatt and Chadwick are currently putting together a website for Miracle Mile fans, with original artwork by Chadwick available for purchase “down the road in 2015,” according to De Jarnatt. —Ed.]

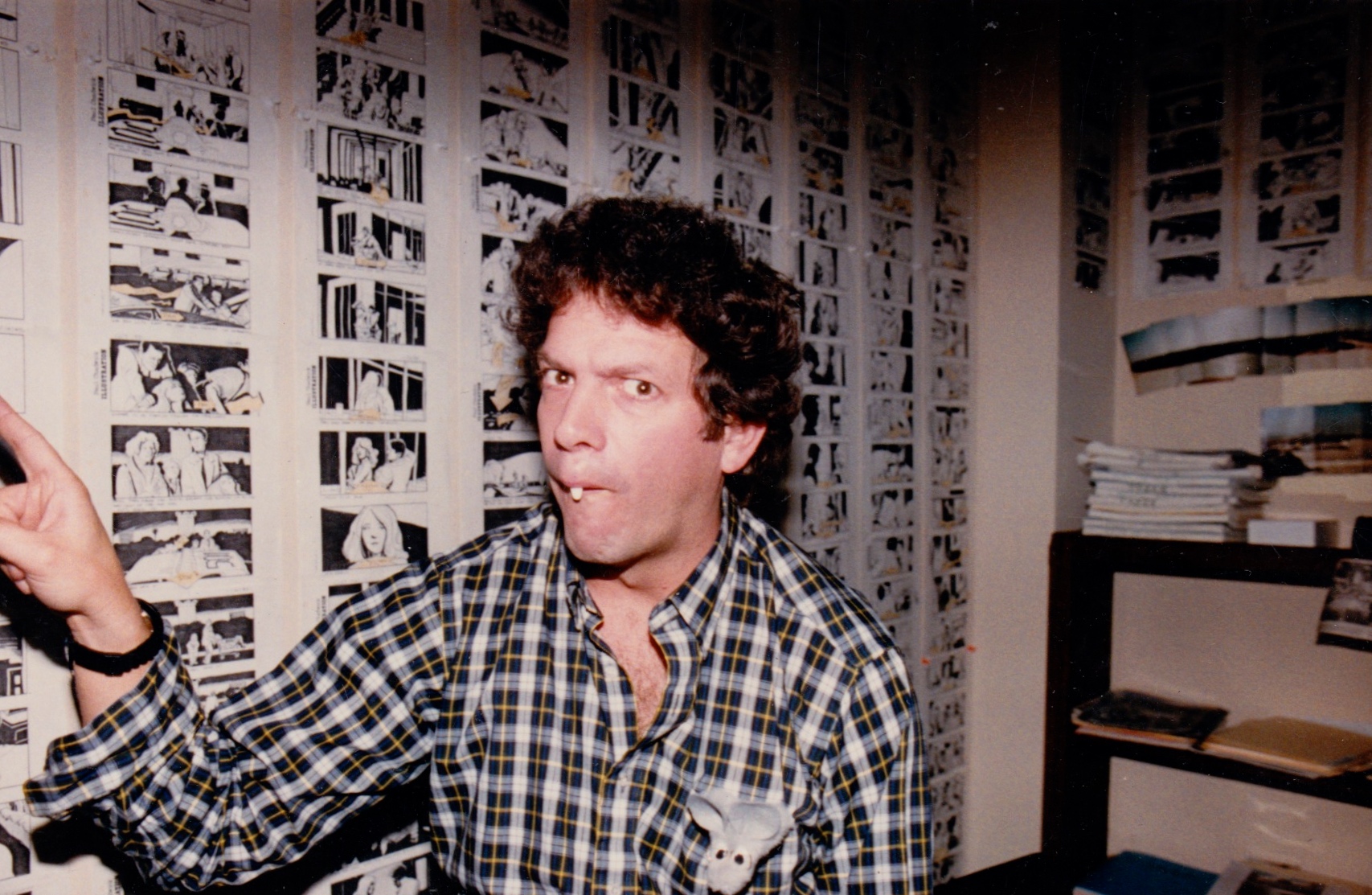

De Jarnatt doing his impression of either a mouse in a beer bottle or a rat in an L.A. palm tree as he stands in front of Paul Chadwick’s storyboards for Miracle Mile (1989)

RC: In Miracle Mile it seems apparent that you’re an Alfred Hitchcock fan. Is that correct? How did you end up directing the segment of the Alfred Hitchcock Presents pilot that’s based on a Roald Dahl short story [“Man From the South,” 1948; the pilot aired as a two-hour NBC “movie of the week” on May 5, 1985]?

SDJ: “Tarzana” played at festivals in 1978, and between ’78 and ’84 or ’85 or whenever that Hitchcock thing was, I was getting ready to make Strange Brew, I was getting ready to make a Hell’s Angels movie with Mickey Rourke — I discovered Mickey before he’d ever done anything, but that movie fell apart. You know, you’re attached to various movies, but I also turned down, like, 30 movies. I had all this heat, and I was this arrogant little auteur. I just wanted to make Miracle Mile. I didn’t want to do anything else.

I got the best segment. First time on a professional set, and I get to direct John Huston, Kim Novak, Tippi Hedren [as well as Melanie Griffith and Steven Bauer, who were married from ’82 to ’87]. Huston was on oxygen at the time, right after he directed Prizzi’s Honor, so I did a lot of one-take things. But everyone was on their best behavior around him, and I got along splendidly with him. Such an honor. I gave him a copy of a dictionary of angels I had — he was prepping to shoot an adaptation of Anatole France’s The Revolt of the Angels — and he was fascinated talking to Melanie about Tippi’s animal compound with ligers and tigons, and with Steve Bauer about his father’s involvement with the Bay of Pigs. [Bauer was born in Havana in 1956 as Esteban Ernesto Echevarría Samson. —Ed.]

It turned out great, and it was an extremely pleasurable experience, but they almost fired me at the beginning of the week because I kept rewriting; we were shooting at Caesars Palace and I was changing a few things. Television is weird: once they’ve approved something, it’s like, Okay, now that’s what we’re doing — no more creativity.

I came in on schedule, but once again I was very arrogant: the TV movie got big ratings and NBC ordered a series, and Universal offered me, like, $300,000 a year to write, direct, and produce television. And I said, “I don’t want to do television — I’m a filmmaker.” I wrote “Jaws 4” instead. One of many things I wish I could go back and go, “No, I’ll take that job, please.”

Muriel checks both tanks again, scanning above and behind for predators. At first her view holds none, but as snouts triangulate the beacon of Jimmy’s blood, a dozen killers begin stacking up like jets over JFK, circling round them.

The largest of the great whites slaloms her way. Muriel hangs limp, trying to impersonate kelp. She feels the shadow moving swiftly above again. The blue whale dives to thwart the attack, ramming the shark headlong like a bumper car, bruising cartilage, then smacking a flipper — sending it tumbling away.

Muriel is astonished by what her mega fauna friend has done on her behalf, as it pirouettes some marine equivalent of a touchdown dance. She is transfixed as the eye of him passes near, blinks slowly, then glides on.

—from “Her Great Blue,” New England Review, 2013

RC: So you did an uncredited rewrite on Jaws: The Revenge?

SDJ: No, this was a “new concept” draft set in Malibu, with surf punks. I wrote it for Frank Price [then the head of Universal Pictures], and it was more like Tapping the Source with a megalodon shark. All I know is that I did some work, and when I came back from shooting Cherry [Cherry 2000, De Jarnatt’s feature-film directorial debut, which was shot in 1985 but not released stateside until ’88], Frank Price got in a fistfight with Sid Sheinberg, who ran MCA [Universal’s parent company]. And Sid Sheinberg’s wife, Lorraine Gary, played Roy Scheider’s wife in the first two Jaws movies. I had no part for her, so, needless to say, it didn’t get set in Malibu. [Jaws: The Revenge, released in 1987, involves Gary’s character, now widowed, being stalked by a great white all the way from New England to the Bahamas. —Ed.]

I also wrote a Gremlins sequel that was set in Vegas, but the movie ended up being set in New York [Gremlins 2: The New Batch, 1990]. You know, everybody in Hollywood, when you’re in the game and sort of on the list, everybody’s rewriting everybody. Charlie Haas, who’s a great writer, ended up writing Gremlins 2. I think 15 people had all done drafts for it, and that’s still the way things go. And I actually think it’s unfair of the Writers Guild to just limit the writing credits to two or three people. I mean, the guy who does craft service for two days gets his name in the credits, but the writer who might have written every line that you like in the movie is unknown.

RC: There was a New Yorker article probably nine years ago about those Writers Guild rules for screen credit, and one of the movies it focused on was the Hulk movie that Ang Lee directed. And it was well written, like all New Yorker articles are, but the guild rules were so confusing even when laid out as clearly as the writer could that I still didn’t understand.

SDJ: (laughs) You know, I love the guild. Thank God for both guilds — I’m living off the ample pensions of what was paid in over the 27 years that I worked. Or 12, depending on my age.

RC: (laughs)

SDJ: I’d always go on strike with them. Well, if the Directors Guild ever goes on strike — they never do. And the Writers Guild keeps asking me to arbitrate on a script, but they never take my advice. I want everybody to have credit, and they want it just to be two, three people at the most, and to me — I’m sorry — it’s not the truth.

That’s why I think, going back to Carver, the Gordon Lish edits and the other stuff, that’s just fascinating for any writer to know. I’d love to read every editor’s edits of every great piece of work, and there’s not a better MFA program to go through than reading all that.

RC: There’s a D.T. Max article if you haven’t seen it — I was procrastinating in graduate school while working on some paper — it may have been in The New York Times Magazine, I think, in ’98, where he went through Lish’s papers at whichever university has them. He mentioned Don DeLillo and Gordon Lish being friends, and Lish had written a letter to DeLillo that said, basically, “I’m gonna tell people, because they think Carver’s stories are so great, but I took out all the sentimental crap.”

SDJ: The editing has a huge effect on those stories. And even though in my own stuff I like excess, Lish’s edits are what made that all work, and it was a huge influence on everybody. To me, it’s like, whatever the truth is behind anything should be known, and it’s sad when it’s not. But sometimes you don’t want to know certain things about people.

RC: That was Don DeLillo’s point: “You’re just going to confuse people. They don’t want to know.”

Let me go back to something: how did you get cast in the Ringo special?

SDJ: If you look on my Facebook page somewhere, there’s a clip where I’m sort of a ’50s greaser.

RC: With Greg Evigan — “B.J. or the Bear,” as you said on your page.

SDJ: Yeah, that’s the other guy. I was never going to be an actor. I just used to go to school, like Andy Kaufman, as this character, and I would be in character for the day. And I would have a switchblade, and I would shove people up against the wall. One reason I’m not very good and not very subtle as an actor is I would just get lost in the character; it was a lot of power.

Anyway, I used to do that in college, and somebody who knew me was working on the Ringo Starr special and they needed a ’50s greaser. I got down there, and I think the director [Jeff Margolis] liked me, but the writer, Neal Israel, said, “Take the grease out of your hair, change your wardrobe,” and I grabbed him and I shoved him up against the wall. Then the director said, “I want you to do the better part.” Poor Greg was very disappointed. But I couldn’t remember my lines — I think in the outtake on YouTube you can see me calling Ringo the wrong name or something. (laughs) So I got the lesser part, as I should have. It worked out for the best.

RC: That special aired in April of ’78, and I thought, That’s the same year as The Star Wars Holiday Special, which also had Art Carney in its cast. Did Ringo air on CBS too? [It aired on ABC, thus destroying Robert’s conspiracy theory about Art Carney foolishly signing a lifetime contract with CBS during his stint on The Honeymooners in the ’50s. But Neal Israel cowrote Ringo with his Police Academy and Real Genius writing partner, Pat Proft, who also worked on The Star Wars Holiday Special, and Princess Leia herself, Carrie Fisher, sings a duet of “You’re Sixteen” with the Beatles’ former drummer. —Ed.]

SDJ: You know, I didn’t see it until ten years later. The night it aired I went to call my mom to say, “Hey, I’m gonna be on TV,” and she goes, “You’re on TV right now.” I came back in the room and I had missed it.

But, ironically, since you talked about Star Wars, these friends of mine, Jim and Ken Wheat, they were filmmakers at this college I went to, Occidental College, and they went to the movies, like, three times a night. I wouldn’t have gotten into film if it weren’t for them. I grew up in a little logging town; I was mainly a track jock, and I thought I was going to go into biology or something. They ended up directing an Ewok TV movie for Lucas.

RC: I was gonna say: did they do The Ewok Adventure? [Ewoks: The Battle for Endor, actually, a 1985 follow-up to the previous year’s Ewok teleflick. —Ed.]

SDJ: Yeah, and produced a Scorsese movie [the documentary American Boy: A Profile of Steven Prince, 1978]. They’re good guys.

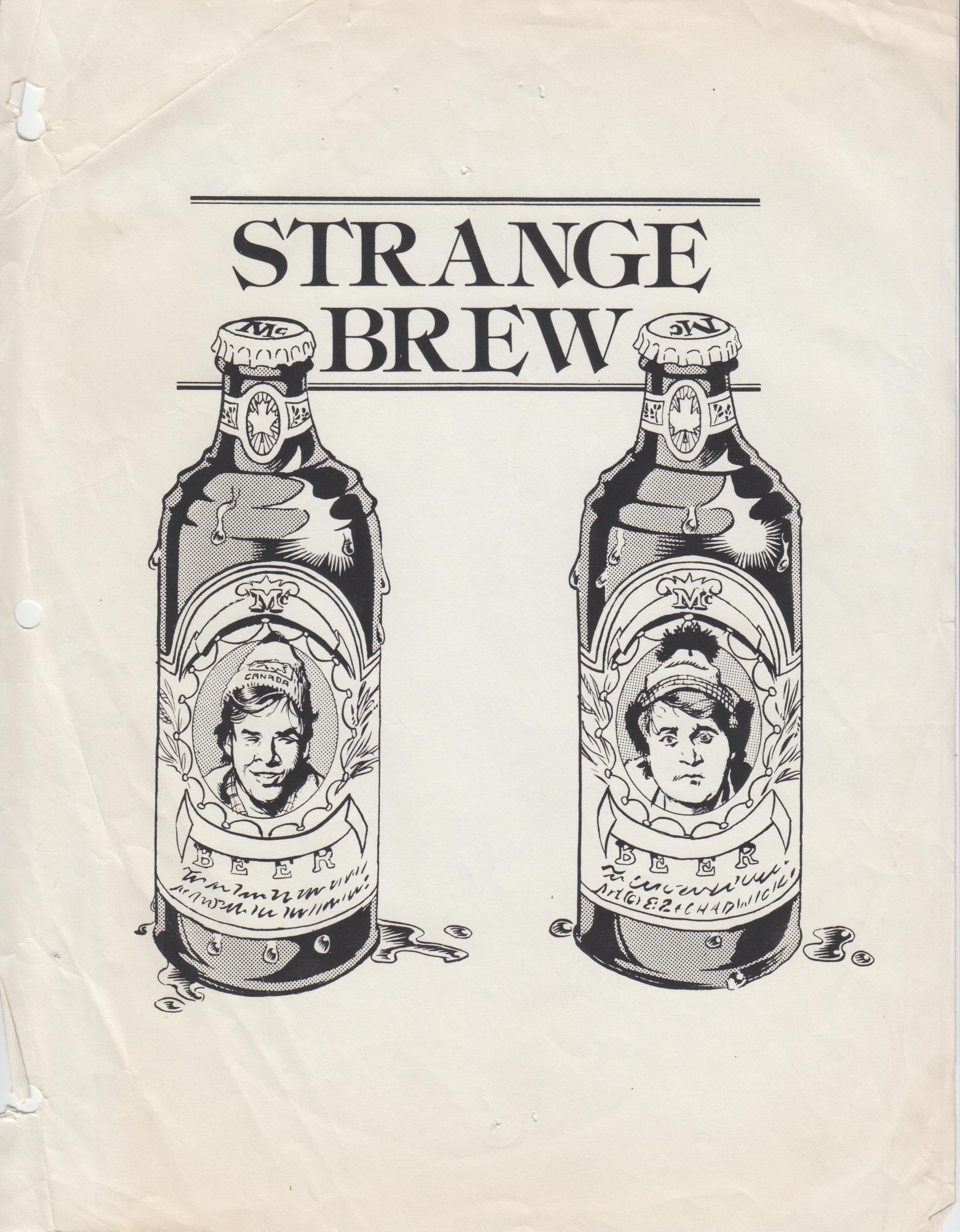

Paul Chadwick’s illustrated cover of the Strange Brew screenplay

RC: Strange Brew came out just three months after Return of the Jedi, but there’s a joke in the first hockey scene, where Brewmeister Smith [played by Max von Sydow] is getting patients from a mental hospital to play hockey against each other, or just knock each other down, and Dave Thomas has on the black hockey mask—

SDJ: Oh, and he goes, “I am your father”?

RC: Yeah, and then Moranis says, “He saw Jedi 13 times, eh?” And Thomas and Moranis are in that scene with Angus MacInnes [as ex-hockey great Jean “Rosie” LaRose], who — I didn’t know this when I first saw Strange Brew — is in Star Wars.

SDJ: Oh, is he?

RC: He’s one of the X-wing pilots attacking the Death Star.

SDJ: I remember him from Atlantic City and some other stuff. He’s a good actor.

To me, the most preposterous thing about Strange Brew — I mean, I’ve gotta tell you, when I first saw a screening I thought it was the worst movie I’d ever seen, and I wanted my name taken off it. (laughs) And then all of a sudden it had this cult following, and then, finally, “Oh, I guess I’ll embrace it. My name’s on it — I helped contribute something.” But I was just cringing through the whole thing. And I felt so bad for Max von Sydow, one of the greatest actors in the world. We were trying to get him, and Dave and Rick actually got him. His agent convinced him: “The kids really love this, and it’ll be great for your career.” And he was like, What? You know, toilet jokes and buck teeth.

RC: (laughs) Dave Thomas says in that interview from 2000 that the buck teeth were von Sydow’s idea.

SDJ: Now, that, I have no idea. It could very well be. But I must say, the movie has its charms. It bombed, but this happens in Hollywood all the time: there’s this new, hot thing, and you’ll see it with actors who nobody’s ever heard of, like Benedict Cumberbatch or Chris Pine. And I know how that works: I remember seeing Chris Pine steal one scene in some Jeremy Piven movie with a bunch of assassins [Smokin’ Aces, 2007], and I went, Oh, that guy’s gonna be a star. Hollywood works that way — about three, four years ahead of the public — but a lot of times, you know, a skit on Saturday Night Live or something is stretched into a movie. But SCTV had a really small American audience — not among Hollywood hipsters, but among the public, so Strange Brew had to find its cult years later.

RC: Well, “Take Off” had at least been a Top 40 hit here.

SDJ: Yeah, it was getting around. It got that buzz.

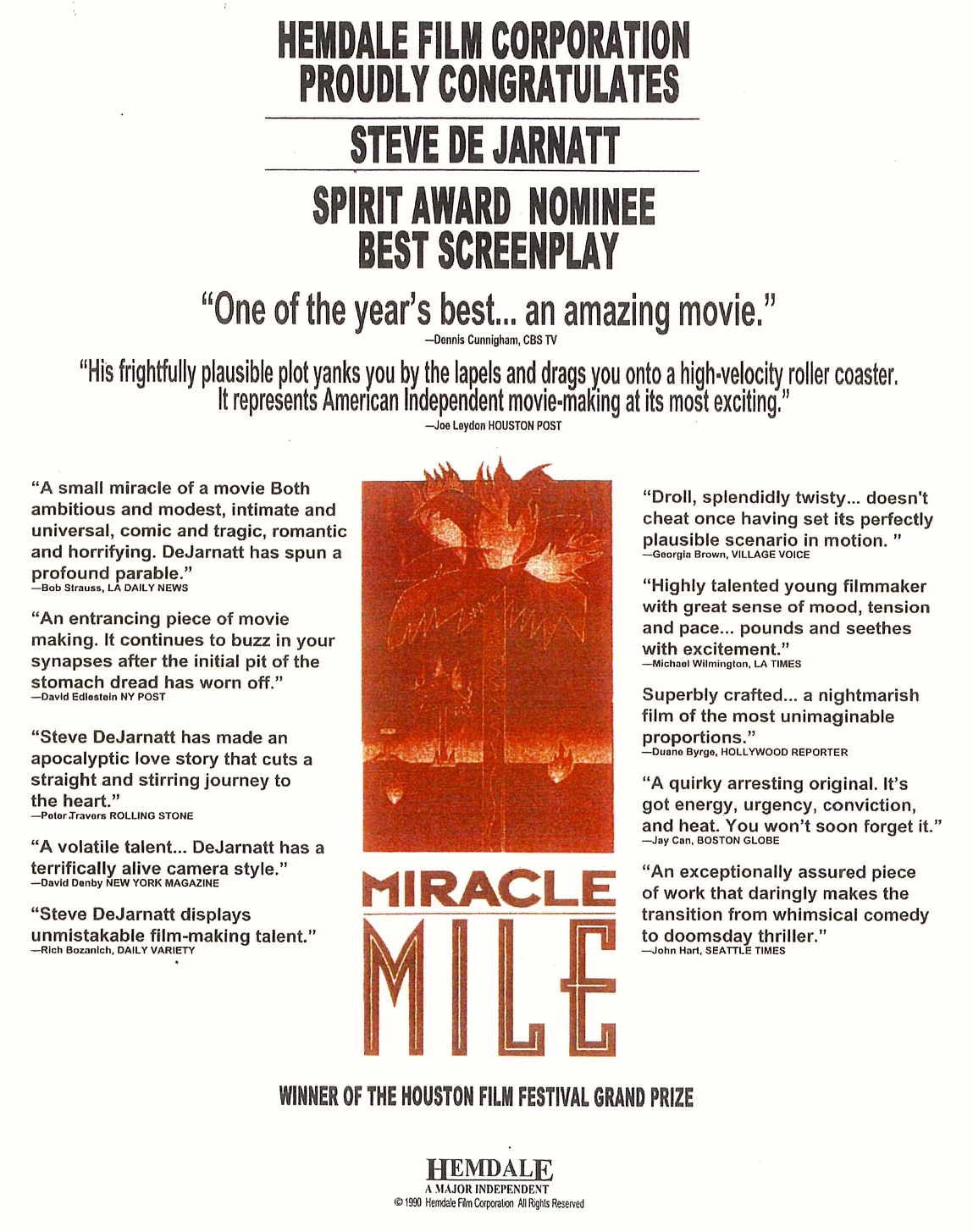

RC: When you set Miracle Mile up with John Daly and Derek Gibson at Hemdale, was that before or after they’d produced Platoon?

SDJ: Before Platoon. I was originally going to make it with Orion, where I directed Cherry 2000. Both companies went bankrupt, so I guess I helped.

RC: (laughs) I just saw a little bit of a clip from a film festival where you and Anthony Edwards—

SDJ: Yeah, there’s that thing, and I skyped an interview from Austin or something, and I probably rattle off some of the same lore.

RC: Well, I didn’t watch the whole thing — I’ll let you repeat whatever you want to repeat. But Miracle Mile came out five days before the third Indiana Jones movie, and you said that it did okay against Road House opening weekend.

SDJ: I think it had maybe two, three weeks — it opened wide, with TV advertising, as an action movie — in New York and L.A. and did okay, and then it was just drowned. But I have no complaints, because they actually wanted to wait till the fall and do the art-house release strategy. It had already been completed for almost a year, and I just said, “No, I want it out, please.” So, I can’t complain that anybody botched the release or anything.

RC: You made the movie you wanted to make, I presume.

SDJ: Within reason. As I like to say, I would go back now with a CGI budget and change Mare Winningham’s red mullet and a lot of ’80s hair and stuff.

RC: (laughs) Don’t be like George Lucas, because I have a feeling he would erase Harrison Ford’s ’70s sideburns in Star Wars if he could.

SDJ: I had to endure a lot with Hemdale, but I must say, John Daly, I gotta love the guy. He’s not with us anymore, and I guess nobody showed up at his funeral. I didn’t know about it; I would’ve gone. I was one of the few people, probably, who ever made a movie with him that still talked to him. He hugged me like a long-lost son.

If you wanted your money, forget it. I was owed three or four hundred thousand on Miracle Mile — because it did make money in video rentals. But you did not see your money. He would steal your money. But Jim Cameron and Oliver Stone should kiss his ring, because they had done Piranha II and The Hand and they could not get arrested, and he bankrolled them [on 1984’s The Terminator and 1986’s Salvador and Platoon, respectively]. No, they didn’t see their profits, but they got their careers going in a huge way.

RC: I just saw Miracle Mile for the first time, on YouTube — Cherry 2000 is there too, but only in Spanish, it turns out, so I couldn’t watch that one — and was wondering if the third act in the movie was the same as the one in the original script. Because I was thinking, when looking back at “Rubiaux Rising”—

SDJ: You know, I realized that after I finished “Rubiaux Rising” — that, uh-oh, the water’s rising and people are drowning again.

RC: Oh, I didn’t even think about that. I just thought about the tomatoes Rubiaux sees and is he imagining them, almost like the phone call Anthony Edwards receives in Miracle Mile.

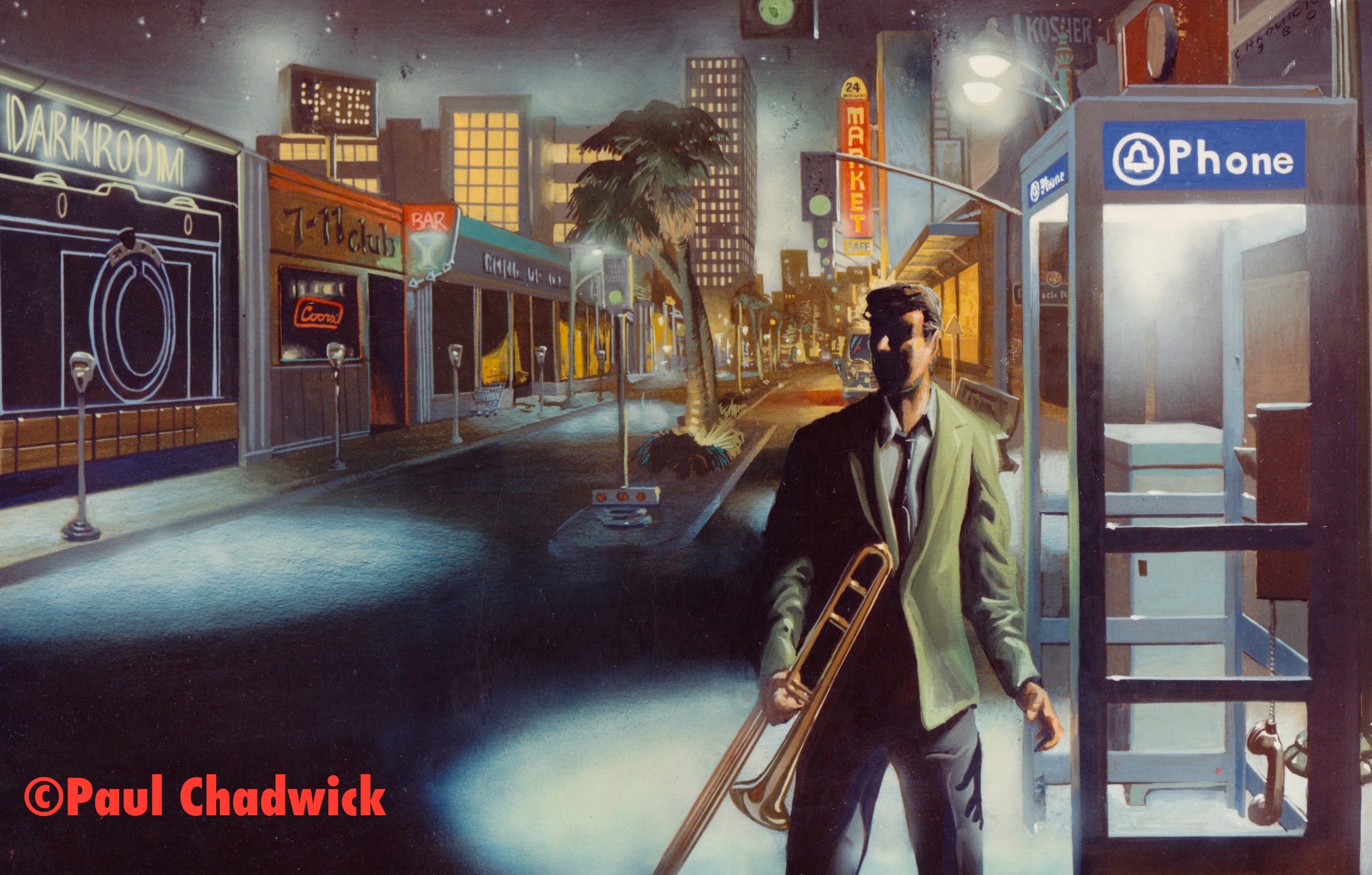

four of Paul Chadwick’s storyboards for Miracle Mile

SDJ: Warner Bros. loved Miracle Mile, and they wanted to make it. Mark Rosenberg was the VP of production — a really interesting guy who was once in the SDS [Students for a Democratic Society] — and Alan Rosenberg, his brother, plays the young street sweeper in the movie—

RC: That’s his brother? [Alan Rosenberg is perhaps best known for playing Cybill Shepherd’s ex-husband Ira on the 1995-’98 sitcom Cybill. —Ed.]

SDJ: Yep, that’s his brother. And, essentially, he’s playing Mark — he’s playing a political guy. The movie only exists because I went in and pitched Mark. Tony Bill, who had produced The Sting — when you were a young filmmaker coming out of the AFI or wherever, he found you and he took you to Warner Bros. and got you a deal. And so Marty Brest had a deal, and they did Going in Style. And Amy Heckerling had a deal, and I followed them to Warner Bros. You know, I went in and pitched maybe five, six things, and then down on my list was this thing in real time where you find out that we’re shooting our missiles at the Soviet Union, and you don’t know if it’s real or not.

I pitched that to Mark, and he went, “Great,” and a year later I turned a script in — which I actually wrote in three weeks, but I agonized over it for a year and wrote, like, 200 pages before the phone rang. And they liked it and were gonna make it, and then they wanted it for Twilight Zone: The Movie.

RC: Yeah, I wanted to ask you about that.

RC: Yeah, I wanted to ask you about that.

SDJ: I wasn’t actually even aware of that. That was a bit later. Basically, they wanted to make it, but they didn’t know what they wanted to change, so they said, “We need to put a $150,000 writer on it,” which at the time was a lot of money — the top guy. They paid me guild minimum to write it — $18,000 or something — but once you start getting into development hell, then you can never get your script back. So I arrogantly said, “Can I have it back? I want to go make it.” And they let me. They don’t do that anymore. They will not give it back to you. (laughs)

But I even got a free year of option [i.e., De Jarnatt was able to maintain ownership of the screenplay], and then I had to option it for another two years — Bob Davi [The Goonies, Die Hard, Licence to Kill] and his sister scrounged up the option money at least once, or maybe twice, during that time — and then it came up that I had to either buy it outright or other people could buy it, and there were other people who were gonna buy it, so I basically gave Warner Bros. every penny I made off Strange Brew and bought Miracle Mile, then spent another six, seven years getting it made. (laughs)

And Mark came back after I’d bought it back from him, and said to my agent, Jim Berkus, who’s one of the founders of UTA — he’s the Coen brothers’ agent — “We’ll give Steve four hundred, five hundred thousand dollars for him to not direct, and we might want to change the ending or have [Edwards’s character] wake up and it’s all a dream.” And Jim Berkus is telling me, “You’re the highest-paid writer in town next to Robert Towne and William Goldman. Look what I’ve done for you.”

And I said no. That’s how arrogant I was.

RC: But you got to direct the movie you had written.

SDJ: I have no regrets. I was getting ready to make it for $2 million with Nic Cage … Kurt Russell was gonna do it … Sting … just all these different ways it was gonna go. But I’m thrilled how it worked out.

De Jarnatt, standing to the side of the camera, on the set of Miracle Mile in 1987

RC: Do you know about Walter Chaw’s 200-page monograph on Miracle Mile?

SDJ: Yeah! He talked to me, and I have a copy of that somewhere, and I want to get another one. I was very moved reading it, because it’s, like, about the effect of something I did on his life.

There’s another guy out here, who’s just gone through a terrible tragedy — Scott Bradley, do you know him?

RC: No.

SDJ: He’s a writer, and it’s the same thing: Miracle Mile had a huge effect on him. I don’t know, I’m always astounded. When I do get that short-story collection together, I’m gonna go on the Internet and find every person who likes Miracle Mile (laughs) and go, “Hey, here’s a book for you.”

RC: (laughs) So they can give you a blurb?

SDJ: You’re supposed to tweet about what you ate for breakfast. I mean, I post a few things on Facebook a couple times a week, but all these agents encourage you to have this big presence and tweet. I’ll do it a bit, but I’d rather just try to find people, whether they’re Strange Brew fans or Aeon Flux or X-Files or …

RC: American Gothic?

SDJ: Yeah, that has a little cult. I mean, the ’90s — some of that’s on my IMDb page and some of it’s not, but, you know, I did become a sellout. After Miracle Mile I still turned down a few things, and then I started writing television pilots. I ended up writing 15 pilots, got 4 pilots made, and worked on a few staffs. That’s how I got my pensions — from actually working.

TV now is the place to be if you’re a writer. You’re the king — the directors work for you. There’s some excellent stuff on; I’m addicted to several shows.

RC: As far as apocalyptic stuff goes, there was something from Steve Almond recently in The New York Times Magazine. He was writing about The Day After, which aired on ABC in 1983—

SDJ: That helped get Miracle Mile made. I mean, Miracle Mile was certainly out there trying to get made long before that, but The Day After was a phenomenon and proved there was an audience for a bleak movie. I had weird feelings about it, because I did want to be the one who came out of nowhere, but it did help Miracle Mile get made.

RC: I can see people rediscovering Miracle Mile partly because I’m obsessed, sometimes against my better judgment, with The Walking Dead.

SDJ: You know, I have not caught up with that. I watch Homeland and Breaking Bad. But those are best when you can get the DVDs and just sit there and binge on them.

RC: One thing Steve Almond said about apocalyptic stories these days is, “There’s a deep cynicism at work here, one that stands in stark contrast to the voices of even a generation ago.” He feels they’re now more about violence than about man’s conscience, trying to prevent what could happen. Though with Miracle Mile I don’t see it as having a moral you’re trying to teach, it’s just “what if?” — which is how most great stories start.

SDJ: It’s a “what if?” — Chicken Little. People talk to me about remaking it — I have no interest in doing it again — and the only thing I would say is, the original script — I changed it, nobody made me change it, so it might’ve been a mistake — but the original script, which I do think is stronger, was about an older guy. It would’ve been, like, Gene Hackman, or these days the guy who plays Walter White [Breaking Bad‘s Bryan Cranston] would be perfect. You know, an older guy, a trombone player who’s in town and barges in on his ex after 15 years, so you have a lot of stuff to deal with rather than them meeting and barely knowing each other.

I think it had an emotional core that would’ve been stronger, and if somebody does remake it I would hope they’d go back to that.

RC: I don’t know if you know about this on IMDb—

SDJ: You mean, “How hideous is Mare Winningham’s hair?” (laughs) I can’t look at those [message boards]. I have my supporters, and then there are all these people who don’t just not like the movie, they hate it. They think it’s the worst movie ever made.

RC: Well, there was one comment where someone said, “This is one of my favorite movies. I loved the ending. I met someone who hated the ending and wanted to punch me”—

SDJ: Yeah!

RC: —”so I knew it was a good movie because it could get that kind of reaction.” I hadn’t seen the movie yet when I read that comment, so when I did I was thinking, Wow, he really took it there.

SDJ: I remember our test screening was in Secaucus, New Jersey, and there were tough guys on their dates crying in the bathroom afterwards. I thought, This is great. And the feedback was pretty good. I mean, it was like, 75 percent liked it, but [the audience-research people] wanted 90, or whatever a “great” score was: “Oh, it’s too depressing.”

I must say, there are only two cuts in the movie that John Daly made me make. One, we actually did have the light coalesce into two diamonds that floated away at the end. He went, “That’s too upbeat. Let’s take that out.” I was on the fence — I could go either way. And then there’s a shot with Mykelti Williamson going up the escalator where he was too bloody.

You know, you don’t usually get a studio head who goes, “Let’s go for the bleaker ending.” I gotta love John Daly.

Across the Nebraska state line Ned crests a knoll, heading toward the lights of the next small town, Byrd peaceful in seizureless sleep. Ned observes the verdant hue of the furious cluster of cumulonimbi boiling low above them. Far off something like gunfire comes closing fast — crack-crack-crack — so loud it shakes bones. A shattering, then again, then too many to count. Ned cranks up the wavering classical station to drown the frightful sound, only making it all seem some blasting movie trailer. The windshield gets bashed again and again as the Saab pulls beneath a narrow train trestle for some small cover. Byrd wakes, showing not a shred of fear, and Ned hugs him, praying a funnel hasn’t formed that could snatch them skyward at any second.

As the din weakens, Ned realizes it’s only the ass end of the maelstrom, voiding its burden in fist-sized shards of hail. Out in the headlights, as far as they can see, glass meteors streak and dash to pieces. Some bounce and dance themselves to a stop. Ned and Byrd grin ear to ear, rapt in transcendental awe — then the heavenly spigot shuts off as suddenly as it began, leaving the road crystal-strewn, faint crackling all around them.

—from “Mulligan,” The Cincinnati Review, 2012 (also anthologized in New Stories From the Midwest 2013)

RC: For “Mulligan” you said in The Cincinnati Review that you did read about the 2008 “safe haven” law in Nebraska but that most of the story was from your imagination.

SDJ: Yeah, I researched it a little bit. Sometimes I collect a lot of research but I don’t necessarily want to use it, and I usually want to write the draft before I have too much. I have a big project about the ’39 World’s Fair, and I just collected so much stuff and I never got around to writing it. Sometimes you have to just dive in. If the research fits, it does. If it doesn’t … That’s why I set “Mulligan” out in the sticks, where maybe it could happen rather than in a city or something.

RC: And with “Rubiaux Rising,” the story that Gus Windus tells Rubiaux about the rats eating a guy?

SDJ: Oh, that’s just sort of made up. That goes back to torture and the Inquisition and those kinds of techniques. That never happened. That’s just a guy freaking somebody out.

RC: One thing I wanted to ask too: have you traveled a lot in your life?

SDJ: You know, somebody else said that too. I have another story that will probably be in the collection that was in Santa Monica Review, about a guy who’s born during an eclipse, and his parents chase eclipses. And it’s set in Angkor Wat, the opera house in Manaus, all the great places in the world, and everybody goes, “Oh, you’re so well traveled.” And it’s like, No, I’ve been to Italy a few times.

RC: Are you curious to travel? Because even in Miracle Mile, when the characters from the diner are getting in Fred the cook’s truck, Denise Crosby’s character says, “Antarctica — we’ll go there,” and she mentions some facts about Antarctica. So are you just well read when it comes to—

SDJ: You know, like I said, I was a jock, and I took two and a half years of good liberal-arts things and then just went totally into film. But I’m a book collector; I’m moving thousands of interesting history books and weird books up to this lodge in Port Townsend. I just graze stuff and find out all kinds of things and put it in my writing, and I just assume everybody knows if I know, so I’m always sort of shocked when I know something that … you don’t know. (laughs)

RC: But I like in “Mulligan” how you never name a state. It’s always a nickname: the Flickertail State, the Show Me State.

SDJ: I found the book that I learned all that stuff from. My girlfriend has a 12-year-old and an 8-year-old, and so we were quizzing each other on the state nicknames just the other day.

I think you said in an e-mail you’d heard about “Mulligan” and thought it’d be funny [based on a short synopsis]. I got to be a scholar at Bread Loaf [an annual writers’ conference in Middlebury, Vermont] this year, and I read just the very beginning of the story, but when I went onstage and said what it was about, everybody started laughing. And for half the thing they’re laughing. I was going, “Guys, it’s gonna get a lot less funny,” and then, finally, by the end they’re going, “Ohhh, okay.”

Miracle Mile too: I’ve sat in screenings and the audience is laughing till [the main characters] are in the tar, practically. It’s crazy.

RC: Well, there was that thing that I mentioned on Facebook to you, that on the British Academy of Film and Television Arts’s website Charlie Brooker gave Miracle Mile the award for “biggest lurch of tone” of any movie. I don’t agree with him that it starts out as a “rom-com,” but the Tangerine Dream score does help put it across as a romance.

De Jarnatt at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, August 2013 (Charles Baxter, author of The Feast of Love, can be seen in the background.)

SDJ: And that was somewhat intentional. I generally tell people, “Listen, it’s gonna be a very sappy, fluffy, bad-’80s-hair love story, and then it’ll get less sappy and fluffy as it goes on. Just bear with it.” But I’ve got a story I’m ready to send out now, it’s 10,000 words — I workshopped it at Bread Loaf, and I’m sort of ignoring all the notes (laughs) — and it’s two stories. It’s an old farmer losing the farm to a Monsanto-like company, and then the rest of it’s in Vegas, getting his revenge on them at a convention and falling in with the plushie crowd. It’s a lurch of tone, I have to admit, but I’m trying to make it work. [“Harmony Arm” will be published in The Cincinnati Review‘s Spring 2015 issue.]

RC: Is there a particular time of the day when you feel like you do your best writing?

SDJ: One thing I do miss about the film world, as an actual professional, is somebody saying, “We need a script” — like with Strange Brew — “in ten days.” Great, I can write that. Probably the best pilot I wrote came from “Michael Eisner needs ‘ER in space’ in two weeks,” and you sit down and the stuff comes out of you. You know, when you’re writing fiction in an MFA or a workshop and you gotta bring something to the table, you do it, but otherwise you could squander all your time.

Which I often do, but I roll out of bed and I read and have a coffee at 5:30 in the morning, and if it’s a really good story I’ll finish the story. If not I’ll graze some stories and start either writing something new or generally revise something that’s written. And sometimes that’s all I get done all day. These days I’m moving, so I still try to get an hour and a half in the morning.

Always in the morning. Miracle Mile, I did a lot of writing in the middle of the night, of course.

RC: (laughs) After waking up from nightmares?

SDJ: I used to have horrible nuke nightmares. Today people are sort of going, “Oh, poor kids, living with terrorism.” You know, lightning is a bigger threat. But we were absolutely certain that you were gonna die in a nuclear holocaust.

And, as I like to point out — I probably pointed it out in that Doomsday Film Festival thing with Tony — all the missiles are still pointing at each other, and we’re not on high alert.

RC: I read that some of those old missile silos have been converted into condos.

SDJ: I tried to, with a previous girlfriend — she was an art director — tried to buy a missile silo in Roswell and turn it into a boutique hotel for, like, German tourists or whatever. But it was half filled with water, it’s contaminated — it’s hugely impractical.

SDJ: I tried to, with a previous girlfriend — she was an art director — tried to buy a missile silo in Roswell and turn it into a boutique hotel for, like, German tourists or whatever. But it was half filled with water, it’s contaminated — it’s hugely impractical.

RC: Did Anthony Edwards recommend you for the pair of ER episodes you directed?

SDJ: Yeah, Tony got me the intro. I think George Clooney appreciated Miracle Mile too. Directing the show was a complete pleasure in every regard. An amazing cast, crew — a machine, with zero bad vibes of any kind. I got to shoot a Halloween episode [“Masquerade,” October 29, 1998] and film part of it in Chicago — Dr. Benton [Eriq La Salle] dressed up as Shaft on a hayride.

RC: I don’t know if you’ve seen this, but it was written on the IMDb message board at the bottom of “your” page on January 27, 2003:

This has been driving me crazy for some years now: I nearly fell off my easy-chair a few years ago when the hero of ‘Miracle’ Mile answered the phone in the phonebooth and has the conversation with the soldier.

In 1985 in a creative writing class at Maimi [sic] University of Ohio—

SDJ: Yeah, somebody pointed that out to me, and I’ve never bothered to dignify it with an answer. What year did they say that was?

RC: Nineteen eighty-five. Under that post somebody suggested that the scene came from the Twilight Zone script.

SDJ: Well, Miracle Mile was on American Film magazine’s list of the ten best unproduced scripts in Hollywood the first time they did the list [1983], so it was probably one of the most well-known scripts in Hollywood in the early ’80s. This guy obviously got his hands on it. I mean, in ’85 it’d already been around for six years.

RC: So somebody stole it that way, you’re thinking?

SDJ: I guess. In the book about Twilight Zone [Outrageous Conduct: Art, Ego, and the Twilight Zone Case by Stephen Farber and Marc Green, 1988], the heads of Warner Bros. actually say, “Gee, if we would’ve made Miracle Mile instead of this, Vic Morrow would be alive.”

RC: (laughs) Wow.

SDJ: (laughs) It really made me feel weird, like, “Did I kill Vic Morrow? It’s not my fault.”

You know, maybe once a year I’ll google Miracle Mile to find out if it’s screening somewhere — in Belgium or Brooklyn or something — and then I use Facebook to let people know. But all the discussions on IMDb — I’ll let the people who like Miracle Mile know about the short-story collection, but you can’t get into those discussions with people. You can’t win.

RC: Did Melanie Griffith suggest to Orion that you direct Cherry 2000 after working with you on the pilot of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, or did you suggest her?

SDJ: She ended up in it sort of by default. She was third on the list, and it seemed like a good idea since I’d done the Hitchcock thing with her. That was one of the weirdest— I mean, like I said, I’d turned down 30, 40 features to direct, and one morning I got a call from Mike Medavoy, the head of Orion, who I think I still have a three-picture deal with.

RC: (laughs)

SDJ: Some director had fallen out of Cherry — Irv Kershner [The Empire Strikes Back, Never Say Never Again] or somebody I can’t remember. They were trying to get David Fincher before he’d done anything. Desperate to find a director. And at the time John Daly was in Holland putting $2 million together for me and Nic Cage to make Miracle Mile. And I literally said, “I can’t do Cherry. Nic’s turning down everything else — we’re making Miracle Mile.”

And then an hour later I get a call from Nic’s attorney, who was Francis Ford Coppola’s attorney too — I think it was Barry Hirsch, a really big lawyer — who says, “Listen, Nic’s gonna do Peggy Sue Got Married and a couple of other movies, and then we’ll slot in your little picture in about a year and a half.”

I went, “Forget it.”

“Well, Nic’s on Catalina without a phone. That’s the way it is, kid.”

And I couldn’t get a hold of Nic, so I called up Orion and said, “Send me the script.” And I read 15 pages and went, “Oh, this is pretty weird.” I jumped on the movie, but it was always catch-up; we were never quite prepared. The production designer disappeared, and I cast the guy, who’s doing some really good work now — David Andrews — but he was sort of a newbie, and he and Melanie were fighting, and we were in all these toxic locations, and the sets were never ready. It was just a horrible, horrible experience.

And same thing as Strange Brew: I wanted my name off it for a long time. But it played on a double bill [in 2012] with Miracle Mile at the Egyptian Theatre — the American Cinematheque — and people liked it. I’d never seen it on a big screen before, so I try not to badmouth it now.

the French-release poster for Cherry 2000 (1988)

RC: You hadn’t seen it since you’d edited it?

SDJ: Well, I did a cut [with Edward M. Abroms], and then David Lynch’s editor [Duwayne Dunham] came in and did a cut on it. It’s pretty much the same movie. I loved the score by Basil Poledouris, who’d done my Hitchcock thing. It’s actually most famous for its score — the score had a cult following.

I describe the movie as Planet of the Apes but without the apes. I usually only ran it at “times two” for people so that you could watch it without dialogue; you’d just see a lot of explosions. That was the only way I would allow it to be screened.

RC: Well, maybe on YouTube I could watch it in Spanish after all.

SDJ: The character actors are great: Tim Thomerson’s great, we got Ben Johnson from Last Picture Show, and “Dobe” Carey [Harry Carey Jr.] from all the John Ford movies with Johnson [Wagon Master, Rio Grande, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon].

RC: Brion James …

SDJ: Brion James — exactly. Claude Earl Jones, who’s in Miracle Mile as well. There’s a guy who gets an arrow through his head [in Cherry 2000] who’s the “Babbler” in Miracle Mile. A San Francisco theater actor—

RC: Oh yeah. Spongey [in Miracle Mile]?

SDJ: Yeah. Really good guy — Howard Swain.

RC: Walter Chaw, in the interview I read, praised you when it came to actors and said you had a Tarantino quality, where you really seemed to like actors and know their strengths.

SDJ: I mean, Tarantino is great at getting somebody who did great work and has been forgotten; he resurrects people in a great way. Mickey Rourke, he hadn’t done anything, and I fought for him to star in a movie, and he did remember that, and so I used to work with him on his boxing movie after Diner.

RC: Homeboy?

SDJ: Yeah, I worked on that. And it eventually got made. It was fun to hang out with the guy; it was very much like Entourage. But that’s a whole other story. And I’m rooting for him even though he owes me money — he owes everybody money. (laughs)

The most amazing thing on Cherry is the guy who was the DP had shot Marty Brest’s first film [Hot Tomorrows, 1977], and he shot the beginning of my short film [“Tarzana”]. He was supposed to be this great wunderkind DP — Jacques Haitkin. He actually quit my short, but I hired him anyway for Cherry. And the second-unit DP, Don Burgess, shot Forrest Gump and Spider-Man. The third-unit DP [first assistant camera], Dariusz Wolski, is one of the top guys now [all four Pirates of the Caribbean movies, plus three for Ridley Scott and two for Tim Burton]. The gaffer, Greg Gardiner, shot Men in Black II. They’re all giant people, and Jacques is, like, shooting million-dollar or no-budget movies in the Philippines still. A lot of good people on the crew who went on to other, better things.

Oh, and you should read a short-story collection called Battleborn. Claire Vaye Watkins: have you ever heard of her?

RC: No.

SDJ: Oh, she’s won some big awards for short fiction. It’s a collection, kind of connected — it’s all set in Nevada. For Cherry we shot in all these little places in Death Valley. Her dad was in the Manson Family.

Rocky Vasellino, a.k.a. Steve De Jarnatt

I actually went on another TV show, after Squeaky Fromme and the Manson girls, in character — in my [Ringo] character. (laughs) I haven’t gotten that transferred yet. I hassled the host, Elliot Mintz, who’s kind of a cult figure.

RC: So you were on his show with Squeaky Fromme?

SDJ: Yeah, I went on right after her, before she tried to assassinate whoever.

RC: Gerald Ford.

SDJ: Yeah. And then the guy who founded the Groundlings [Gary Austin] went on after me. It was a show called Headshop, and I wish that was on YouTube, because I have a one-inch tape, but it’s just disintegrated, I think. Elliot Mintz was this DJ in L.A., and then he became John Lennon’s best friend, and then lately he’s been Don Johnson’s manager and Paris Hilton’s manager or something. It’s a weird story, the Elliot Mintz story.

RC: I noticed in your Facebook photos that you’re wearing Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Ramones, Faith No More, and Spiritualized T-shirts, and there’s an L7 reference in “Mulligan,” there’s the reference to “The Roof Is on Fire” in “Rubiaux Rising,” plus that scene in Strange Brew where Bob & Doug think a floppy disk is a square-shaped “new wave” record, and the fact that Harry is a trombone player in Miracle Mile. Would you say you draw inspiration from music in your work?

SDJ: I’ve always loved music, of all kinds, more than anything else. I wrote a Brill Building pilot for Freddy DeMann, who was Madonna’s manager; a “Rockabilly Rebellion” film I wanted the Blasters and Carl Perkins to be in; “Hair of the Dog,” which was on the second “ten best unproduced scripts” list — sort of Midnight Cowboy meets Ace in the Hole, with struggling Nashville songwriters in the mid-’60s; and I got a Fox pilot, “Planet Rules,” made about a huge rock band — John Hawkes was in it, and it came very close [to getting a series order]. I wrote a script for Robbie Robertson to star in for David Fincher, back when he was only directing videos, that Scorsese was going to produce.

the Helios “sidecar” console in its current home at Sonora Recorders in Los Angeles (photo credit: Brent Demone)

I’ve seen a million bands over the years. I have a very limited ability to play, though I dabble. I also obsessively amassed a major collection of vintage analog recording gear, which I’ve let go of most of by now. The prize was a ten-channel Helios “sidecar” console that was part of the Who’s mixing console built for their Ramport Studios, where Quadrophenia was recorded. I had another console I got from Vincent Gallo, a 12-channel Neumann that was supposedly at Chess Records; I think Jason Schwartzman has it now. Also, the Scully eight-track machine from Muscle Shoals that Sticky Fingers was recorded on, and every ’80s rack-effect gadget, compressors, et cetera. I wasn’t qualified to work these — I just rented or loaned them to bands and artists.

A little vanity side biz. Fun while it lasted.

Molly has pulled her own weight in this world since being run off a Pentecostal home just shy of fifteen back in the Tar Heel State. Bus driver was to be her latest bid for plying a trade — on a long and varied list including playing bass in an L7 tribute band and crewing in Alaska during salmon season. She’s managed to book a few field trips up to Rushmore for some smaller schools in the area, but it’s been piecemeal at best. Now she’s been hired to transport the children from the Sleepee Teepee back to Lincoln, some on to Omaha and God knows where.

“How the hell could anyone give up their own flesh?” she’d asked on the phone, but clammed up quick and took the job. To miscarry as many times as Molly and hear such tales made her come half-unglued.

She squints out across the ruby dawn above her aborted cul-de-sac as the bus lumbers down a blank avenue. Only thirty-six of the planned six hundred homes were ever built; the rest of the lots lie fallow along curbed streets and sidewalks gently curving nowhere.

Molly bought here nothing down — in on the ground floor of a good thing, roots for once, a place to raise family. She enjoyed pretending it was a cabin in the woods when she first moved in, helping the workers complete the interiors. The day their pay was stiffed again, the drywalleros shoved the Sheetrock from the truck to rot in a ditch, leaving her with skeleton walls and dangling wires where appliances should be. What had been a din of round-the-clock construction fell to silence. The developer’s phones rang endlessly. Molly’s four months in arrears on her albatross loan, living off the leavings of other abandoned homes, but she has steeled herself to make a stand here, homesteading in the half-formed landscape of the modern dream.

—from “Mulligan,” The Cincinnati Review, 2012

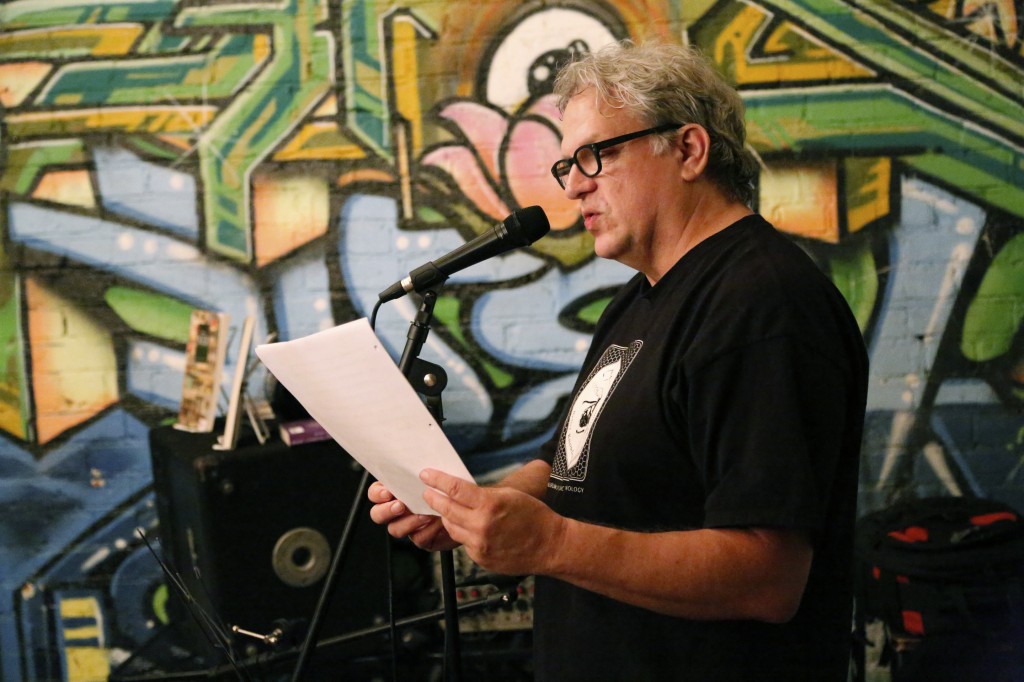

De Jarnatt reading from his work on September 26, 2014, at a New England Review event held at Stories Books & Café in Los Angeles (photo credit: Thomas Moore)

P.S. (POSTCREDITS SCENE):

STEVE DE JARNATT’S RECOMMENDED AUTHORS LIST

• Lou Beach

• Will Boast

• Eugene Cross

• Anthony Doerr

• Julia Elliott

• Steve Erickson

• Gina Frangello

• Jim Gavin (“I would describe him like Ron Shelton [writer-director of movies such as Bull Durham and White Men Can’t Jump]. Middle Men is a great collection.”)

• Tod Goldberg

• Karl Taro Greenfeld

• Michael Griffith

• Lauren Groff

• Adrianne Harun

• Alan Heathcock (“He has a collection called Volt, and he was sort of my consigliere at a writers’ workshop hosted by Tin House. There’s some young filmmakers that are making shorts of some of his stories, and he asked me to give them some Hollywood advice.”)

• Eleanor Henderson

• Caitlin Horrocks

• Eowyn Ivey

• Adam Johnson

• Alexandra Kleeman

• Grace Krilanovich

• Aryn Kyle

• Dylan Landis

• Diane Lefer

• Rebecca Makkai (“Any time I want to feel humbled, she was in Best American Short Stories four years in a row: I think the year with Christine [Sneed], and then my year, and then the two years after.”)

• Anthony Marra

• Mary Miller

• Kyle Minor

• Kevin Moffett

• Téa Obreht

• Victoria Patterson

• Benjamin Percy

• Donald Ray Pollock

• Jamie Quatro

• Suzanne Rivecca

• Rob Roberge

• Jim Ruland

• Ethan Rutherford

• Janice Shapiro

• Maggie Shipstead

• Mark Haskell Smith

• Christine Sneed

• Matthew Specktor

• Ben Stroud

• Laura van den Berg

• Claire Vaye Watkins

• Josh Weil

“… not to mention scads of what I consider to be well-known, established writers, like Richard Bausch, Charles Baxter, Aimee Bender, T.C. Boyle, Rosellen Brown, Sarah Shun-lien Bynum, Bonnie Jo Campbell, Dan Chaon, Charles D’Ambrosio, Stuart Dybek, Barry Hannah, Pam Houston, Jim Krusoe, Cormac McCarthy, Jill McCorkle, Antonya Nelson, Edith Pearlman, Tom Perrotta, Annie Proulx, Ron Rash, Karen Russell, Jim Shepard, Marisa Silver, Wells Tower, Joy Williams, Tobias Wolff, and, of course, Alice Sebold, who I’ll always be indebted to.”

For some free samples of De Jarnatt’s literary work, check out the audio version of “Eggtooth,” winner of The Missouri Review‘s 2014 Audio Contest in the prose category, and “Except, Perhaps in Spring,” named one of the “most read” stories published by the online magazine Joyland this year.

Comments