A sign of a good film and TV production is how well a writer and director are able to add layers of meaning to the main story. With ”Twin Peaks,” David Lynch and Mark Frost are very fond of layers, easter eggs, sleight of hand, and other techniques to muddy up the narrative waters so viewers come away with different interpretations of what they just saw on the screen.

Now that ”Twin Peaks: The Return” is on the glide path to its conclusion, many of the diffuse threads are lining up in ways that are slowly revealing their mysterious beginnings. However, one thread that seems to have slipped past critics of the show is its narrative of middle and working-class whites — and how the last 25 years have been quite vicious economically, politically, and even morally.

Two Worlds

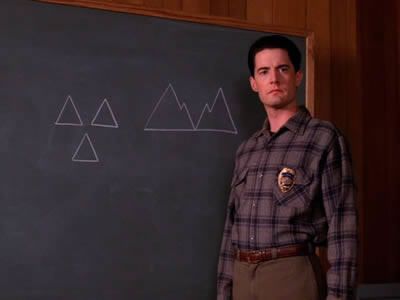

David Lynch’s work (mostly his film work) places a great deal of emphasis on duality. From the rot under the pristine town of Lumberton in ”Blue Velvet,” to the dual lives depicted in ”Lost Highway,” ”Mulholland Drive” and ”Inland Empire,” Lynch’s characters often have mirror opposites in literal form, and within their personalities in conflict with each other and the world (or worlds). ”Twin Peaks” certainly does not shy away from the duality in some of its characters (the most obvious in the first two seasons was the Laura/Maddy duality and Cooper and his doppelganger created in the Black Lodge). The dual nature of humanity leads to a condition where good or evil will dominate in the worlds Lynch creates. Either/or tends to be a starkly simplistic storytelling technique, but sometimes starkly simplistic is what’s needed when being too nuanced masks the importance of what an artist is trying to say about the existence humans have constructed for themselves.

If one compares the first two seasons of ”Twin Peaks” with ”The Return” it’s clear that duality plays out in terms of class, but also the plight of middle and working-class whites. Take, for example, the stylistic aesthetic in the first two seasons of ”Twin Peaks.” The characters live in a small town near the Canadian border in Washington state, yet their sense of fashion, culture and even coffee is not small town. Just looking at their early ’90s attire, it’s clear that Lynch isn’t trying to depict small town life in the northwest. Rather, he’s playing with style in a postmodern way to set up a sense of irony about smashing up urban and rural. Maybe it was Lynch’s PoMo sensibilities that often manifest themselves in his projects, but perhaps he was also reflecting the aspirational hopes of small-town denizens who desire something more than flannel, Budweiser, and Marlboro reds.  One of the most striking images in terms of style is Laura Palmer’s funeral — where friends, neighbors and the FBI agent investigating her death show up to pay their respects in a lot of late 80s/early 90s dress. Where are these people buying their clothes? Oh yeah, Horne’s Department Store where Audrey Horne worked at the perfume

One of the most striking images in terms of style is Laura Palmer’s funeral — where friends, neighbors and the FBI agent investigating her death show up to pay their respects in a lot of late 80s/early 90s dress. Where are these people buying their clothes? Oh yeah, Horne’s Department Store where Audrey Horne worked at the perfume  counter, and an effete Dick Tremayne ran the men’s clothing department. But even Horne’s Department Store is anachronistic in many ways. Sure, most towns have places where one can purchase clothes, perfume, and jewelry, but they usually cater to the tastes of the customer base. Both Horne’s Department Store and The Great Northern Hotel (both owned by Ben Horne) seem out of place in a small, Northwestern rural logging town. But this is Lynch getting the audience to accept at face value that this quirky town of over five thousand residents (or is it 50,000?) — many of whom are working-class loggers, truckers, and mill workers — embrace current fashion with the same elan as the experimental dancers in Mawby’s bar were accepted by Pittsburgh steelworkers in ”Flashdance.”

counter, and an effete Dick Tremayne ran the men’s clothing department. But even Horne’s Department Store is anachronistic in many ways. Sure, most towns have places where one can purchase clothes, perfume, and jewelry, but they usually cater to the tastes of the customer base. Both Horne’s Department Store and The Great Northern Hotel (both owned by Ben Horne) seem out of place in a small, Northwestern rural logging town. But this is Lynch getting the audience to accept at face value that this quirky town of over five thousand residents (or is it 50,000?) — many of whom are working-class loggers, truckers, and mill workers — embrace current fashion with the same elan as the experimental dancers in Mawby’s bar were accepted by Pittsburgh steelworkers in ”Flashdance.”

White Economic Anxieties

But where do class and race fit in this artifice created by Lynch? Well, since we are taking things at face value, we know that the town of Twin Peaks reflects the middle to upper-middle-class culture of its white residents. These are people for whom the American Dream has come true (one ”peak” of those two mountains). Except for characters like Leo Johnson, his wife Shelly (who live on the economic margins), and people like the Renaults and Hank Jennings, most of the other main characters have clean, comfortable homes that are reasonably secure. Laura, of course, is the exception. While we know that she leads a double life (Prom Queen and prostitute), Laura’s home life is such that it, like many of Lynch’s explorations of middle-class culture, exemplifies his exploration of duality. On the surface, Laura’s life with her father and mother seems right out of a 1950s stereotype of white middle-class stability. Her father Leland works as an attorney, her mother Sarah is a stay-at-home mom, but Laura’s parents reveal that they have dual lives, too. Within the walls of this outwardly stable home is constant foreboding and tension. Evil always seems to reside just below the surface of things in ”Twin Peaks” (The other ”peak”), and as things play out, we are introduced to this kind of secret world that (except for a Native American sheriff deputy known as ”Hawk” and Josie Packard — the Chinese wife of the mill owner who we are told died in a boating accident ) is only experienced by the white characters. And for most of the first two seasons of ”Twin Peaks,” the mysteries of the town (propelled by Laura’s death in the first episode) are the focus of this dark soap opera. Lynch is highlighting both the romance and horror of this town, but the drama unfolds in a fairly stable economic environment where high fashion, gourmet coffee, and award-winning pies are the spheres of the middle-class bubbles Lynch pops throughout the series.

The Cosmic Flashlight

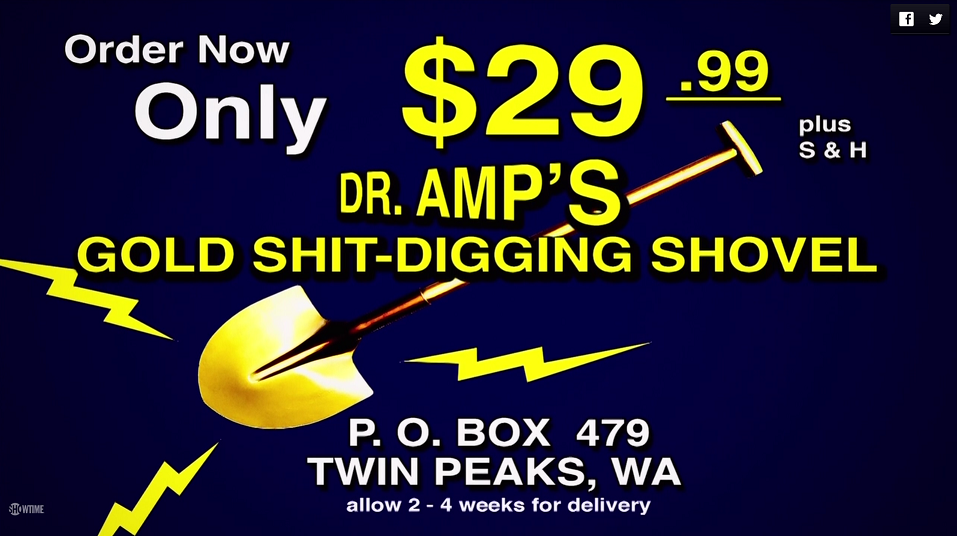

With ”Twin Peaks: The Return” it’s 25 years after the events of the first two seasons took place, and much has changed. If the town of Twin Peaks stands as a metaphor for white middle-class stability that provides a safety net for its residents (even those on the margins), it’s clear that Lynch is showing how that net has been shredded through wars, the consolidation of power and money by big business, and a willing government who rewrites the rules that favor the wealthy — which leaves everyone else to fight over the scraps. The two characters who speak directly about this economic loss are Dr. Lawrence Jacoby and Janey-E Jones. Jacoby was a secondary character in the first two seasons of ”Twin Peaks” but in ”The Return” he has, ahem, returned as ”Dr. Amp” who hosts an Internet streamed video show where, in a kind of Alex Jones/Info Wars way, he inveighs against pharmaceutical companies, the government, loss of liberty, and how we’re all getting screwed by these large forces who have broken their social contract with Americans. Oh, and he also sells gold-painted shovels so people can ”dig themselves out of the shit.” Jacoby’s rants are the ravings of an angry and paranoid old man (much like what we hear on talk radio). However, as the series progresses, and scenes are punctuated with Dr. Amp’s tirades, it’s clear that Lynch is using Dr. Amp’s rantings to put a very fine point on the fact that Twin Peaks (and indeed the whole country) is being ruled by that other ”peak” where evil takes many forms — including a type of capitalism that hollows out the economic bedrock of communities where the both young and old are left with little but low paying jobs, drug addiction, and no economic mobility.

This is made clear when Lynch locates a good deal of the action in Twin Peaks at the Double R Diner (which feels more working-class than it did in the first two seasons), The ”New” Fat Trout Trailer Park, The Bang Bang Club, and the sheriff’s office. At each location, it’s obvious the town of Twin Peaks is no longer the middle-class bubble it was 25 years ago. The high fashion clothes are gone, the wooded luxury of the Native American-themed Great Northern Hotel is reduced mostly to Ben Horne’s office, and the sheriff’s department has a clear line of demarcation between good cops and bad cops. That sense of stability the town used to stand for tilts in the other direction. Violence against women in the form of domestic abuse (and violence in general) drives the story in episode 11 in a big way, but the entire series thus far has been showing the audience how the power of evil in its many forms is destroying white middle-class communities. That’s not to say that Lynch does not have non-white characters in the show. He does — but they are secondary and even tertiary characters whose role in the main storylines is minimal.

”We Are Living in a Dark, Dark Age”

Another place where Lynch locates the action in Las Vegas — a city that was hit hard by the real estate bust that brought on The Great Recession. While there are the usual casino owners who also seem to be crime bosses as main characters, it’s the rows of mostly empty homes for sale in a newish suburban development that punctuates how lives were upended by an American Dream made possible by easy credit — given to people whose jobs didn’t pay all that well — and easy default. A subdivision known as Rancho Rosa (Pink Ranch) is outwardly supposed to be a place where a soft middle-class politeness can thrive. But inside one of the homes is a drug-addicted mother who blurts out ”One one nine” before consuming some kind of opiate that sends her into a stupor — as her young son looks on while sipping on a juice box or eating chips. Rancho Rosa is also the place where a ”manufactured” Dale Cooper clone known as Dougie Jones is just finishing up having sex with a prostitute, and where gangs of car thieves and loan sharks look for easy prey and deadbeats like Jones who can’t pay their debts. Whatever seeds that were supposed to bloom into hundreds of middle-class dreams at Rancho Rosa quickly grew into twisted weeds trapping residents in underwater loans, substance abuse, and a desert landscape as barren as the souls who reside there.

Dougie Jones’s wife Janey-E is keenly aware of how precarious things are for them. While Dougie does have a job, Janey-E knows that he’s a gambler, womanizer, and overall loser of a guy she has hitched her wagon to. Through a fantastical series of events, FBI agent Dale Cooper (who was stuck in what is known as the Black Lodge in another dimension) is returned to the world, but because duality pervades in the Lynchian universe, two Coopers cannot exist in the same dimension. There is an evil Coop (known as ”Mr. C”) who swapped places with ”Good Coop” at the end of season two. However, through a kind of insurance policy Mr. C created for himself in the form of Dougie Jones when ”Good Coop” re-enters our world, he takes the place of Dougie — but his mind is almost wiped clean. Cooper can walk and kind of talk, but his brain is a bit like swiss cheese in that he only has fragmented notions of his previous life. ”Good Coop” sorts of sleepwalks through his new life as Janey-E’s husband — and father to Sonny Jim — but people seem to forgive or ignore the fact that there’s something seriously wrong with this guy. No matter where Dougie goes, his co-workers, boss, strangers, his wife, and son help him in matters large and small. On the one hand, it’s clear that Lynch created the Dougie/Cooper character for comedic effect. But read in another way, one has to wonder if Cooper weren’t a middle-aged white man in a suit with an office job, would a spouse, his co-workers, and boss be so eager to help him if he had a darker skin tone, casual clothes, or was even another gender?

However, while Cooper’s skin tone and gender do give him a pass on things that would have gotten others institutionalized — or thrown in jail — it’s Janey-E, who makes the class argument that times are indeed tough for those whom middle-class life can be wiped away through a job loss — or in Dougie’s case — gambling debts. At one point, Janey-E meets with Dougie’s debt collectors to settle things, but when she finds out the interest rate on the loan Dougie got to place bets on football games, she lay out her views on loan sharking in some very straight talk:

My husband has a job, he has a wife, he has a child. He does not make enough money to pay back fifty two thousand for anything. We are not wealthy people. We drive cheap, terrible cars. We are the 99 percenters, and we are shit on enough, and we are certainly not going to be shit on by the likes of you. So here’s what we’re going to. Without my knowledge my husband came to you for a loan of twenty thousand dollars…you were nice enough to give it to him… but he should have never been gambling like that.

I’m going to pay you back. Now at my bank where we make less than one percent interest on what little money we have, people would be turning cartwheels just to get twenty five percent on any loan. And that is what I’m generously going to give you right now.

Twenty five thousand dollars. That is my first, last, and only offer. [she offers a stack of bills, but snatches them away a moment later]

What kind of world are we living in where people can behave like this…treat other people this way without any compassion, or feeling for their suffering. We are living in a dark, dark age, and you are part of the problem.

In one way or another Janey-E and Dr. Amp get to the heart of what’s ailing white middle-class society: class warfare. Where the powerful prey on the powerless, where downward economic mobility crushes the American Dream, where the side effects of war like violent outbursts, emotional suffering, and substance abuse lead to a society that lacks compassion for others. And what was the genesis of this war? The nuclear bomb that exploded in  New Mexico in 1945. Lynch places clues to it in the office of the character he plays in the series (Gordon Cole) where images of a mushroom cloud, a picture of corn that’s scorched, and Franz Kafka take up wall space. In various guises, we see these images manifest themselves in literal ways (episode 8 in ”The Return” took us deep into a mushroom cloud in a very Stanley Kubrick manner that was reminiscent of ”2001: A Space Odyssey”). The scorched corn image connects with the pain and sorrow of the garmonbozia that the beings in the Black Lodge consume from those they inflict misery upon (and yes, it looks like cream corn, but it also has a kind of black ooze once consumed). And Kafka? Well, the absurdities he created in his stories abound in Lynch’s work, but they also signal that, like Kafka, there are large powers that oppress people into surreal nightmares.

New Mexico in 1945. Lynch places clues to it in the office of the character he plays in the series (Gordon Cole) where images of a mushroom cloud, a picture of corn that’s scorched, and Franz Kafka take up wall space. In various guises, we see these images manifest themselves in literal ways (episode 8 in ”The Return” took us deep into a mushroom cloud in a very Stanley Kubrick manner that was reminiscent of ”2001: A Space Odyssey”). The scorched corn image connects with the pain and sorrow of the garmonbozia that the beings in the Black Lodge consume from those they inflict misery upon (and yes, it looks like cream corn, but it also has a kind of black ooze once consumed). And Kafka? Well, the absurdities he created in his stories abound in Lynch’s work, but they also signal that, like Kafka, there are large powers that oppress people into surreal nightmares.

One of those surreal nightmares is in a scene set in 1956 where a nameless teenage couple walks home in a very ”Leave It To Beaver” fashion after a school dance. The girl goes inside her home after getting a sweet, and somewhat innocent kiss from the boy, where she listens longingly to the radio in her bedroom. Evil arrives shortly after that in the form of beings known as The Woodsmen. These beings come from another dimension through a portal created when the nuclear test in New Mexico occurred 11 years prior. One of the woodsmen — whose face appears scorched — takes over a local radio station where he utters a strange poem that lulls the residents listening to the radio into sleep. However, the woodsman’s poem also awakens a fly-like creature with amphibious legs from an eggshell that flies into the teenage girl’s room and crawls inside her mouth while she’s sleeping. Lynch also has another entity known only as The Experiment that made an appearance in episode 2 when it showed up in a glass box in New York City and ripped apart a young couple while they were in the middle of having sex, and then again in episode 8 where it vomits up eggs that contain the fly-like creatures and the spirit of Bob (an evil entity from the Black Lodge who possessed Laura Palmer’s father, causing him to repeatedly rape her for years). Given all that, Lynch is setting up an epic showdown between the forces of good and evil for the finale of ”Twin Peaks.” However, evil, in the Lynchian world, takes many forms (as does good), and while many viewers of the show love to engage in a deep analysis of ”Twin Peaks” and its breadcrumbs of mysteries, the evils of corporate capitalism also take many forms.

In episode 13, the smiling face of an evil form of capitalism manifests itself in Norma’s boyfriend, Walter. Though we don’t know the exact details, we do know that Norma has gone into partnership with a group of investors (with Walter as the lead investor) and opened a chain of Double R Diners– though they are known as ”Norma’s Double R.” Walter mentions that while the other Double R Diners are making money, the one in Twin Peaks is losing money. The problem? Norma spends too much on pie ingredients. When Norma complains that her pie recipes at the other Double R Diners aren’t as good, Walter tells her, in essence, that he had them cheap out on ingredients (i.e., ”tweaked” Norma’s ”formula”). Moreover, Walter suggests that Norma do the same for her pies ”to ensure consistency and profitability.” She protests by saying that what makes her pies so good is that she only uses fresh, organic ingredients, but Walter has spreadsheets and ”agreements” (i.e., contracts) to bend her artistry to the needs of the Board of Directors.

In a way, small-scale capitalism is presented by Lynch as more authentic, quirky (see Nadine’s Run Silent, Run Drapes store), and a source of greater independence — though it can come at a cost. A case in point is Ed’s gas station. He’s been running his ”Gas Farm” for a long time now, but it seems it’s a lonely venture where sometimes you sit by yourself and eat a cup of soup from the Double R while waiting for someone to roll in and buy gasoline. But that’s the dual nature of Lynch’s world. Lynch has often said the way he constructs his films allows for various interpretations. And while he certainly has things to say in his films and TV shows, it’s up to the viewer to derive meaning from them. Often when pressed to answer questions like ”What does it all mean?” Lynch is evasive. He says the visual language he uses in his work (also known as ”the language of film”) gives viewers the opportunity to answer ”What does it all mean” questions in their own way. Instead of translating the language of film into spoken language, he’d rather let the work speak for itself. Most artists are loath to explain their work. If they have to, it means that they’ve somewhat failed to present their work in a meaningful way. So while I think Lynch certainly has an ax to grind against the forces of corporate capitalism (he did, after all, work in the Hollywood system where every sort of weasel ”producer” probably had ”notes” for him to ”tweak” his work to ”ensure consistency and profitability”), the critique of that system — and linking it to evil — comes out in the bluntest ways throughout the series. The hammer Lynch is using in ”Twin Peaks” is one that, like Dr. Amp’s gold shovels, is trying to illuminate the ”shit” we’re all in — but Lynch also longs for a romanticized view of his 1950s upbringing. That longing has been a consistent theme in much of Lynch’s film and TV work, and if ”Twin Peaks: The Return” is Lynch’s swan song, he seems to want to make clear that while he’s not against someone making a buck, they shouldn’t have to become evil to do it.

Comments