Albums discussed in this column:

- Lydia Loveless, Somewhere Else

- Felice Brothers, Favorite Waitress

- Bob Mould, Beauty & Ruin

- Sturgill Simpson, Metamodern Sounds in Country Music

- The Hold Steady, Teeth Dreams

- Beck, Morning Phase

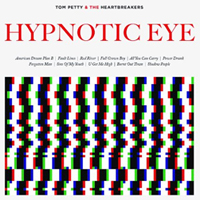

- Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers, Hypnotic Eye

- Ryan Adams, Ryan Adams

- Luluc, Passerby

- Lucinda Williams, Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone

- St. Vincent, St. Vincent

- Duane and Gregg Allman, Duane & Greg Allman

- The Clash, Sandinista!

- Frank Sinatra, Sings for Only the Lonely

- Night Ranger, High Road

- The Beatles, Please Please Me, With the Beatles, A Hard Day’s Night, Beatles for Sale

Sometimes truth comes to us ensconced in the mawkish and saccharine. Think of Barry Manilow singing ”Ships”—communication between parents and progeny can indeed be difficult, Ian Hunter be praised—or John Denver’s ”Annie’s Song,” which is the most significant expression of masculine confidence I’ve ever heard (think John Wayne coulda sung that? I think not).

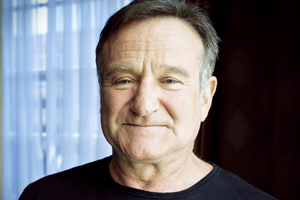

Amidst the virtual detritus that floated around the Web in the wake of Robin Williams’ death this last summer was a quote that struck me as a bit maudlin, but also immeasurably true. Couched in the inexhaustible stream of memes that featured his face—that face that we’d associated with so much laughter and happy moments for so long—and ”O Captain! My Captain!” lines or ”Your turn, Chief” Good Will Huntingisms, was this eye-welling beaut:

You know what music is? God’s little reminder that there’s something else besides us in the universe; harmonic connection between all living beings, everywhere, even the stars.

You know what music is? God’s little reminder that there’s something else besides us in the universe; harmonic connection between all living beings, everywhere, even the stars.

After catching my breath at the beauty of such a thought—and looking straight up at the ceiling, willing the tears back into their ducts, for it was too soon, too goddamned soon—I wondered about the context for the sentiment. Was it an interview, and if so, what had he been asked to elicit such a thought? Had he uttered it in one of the periodic quiet moments in one of his extended manic monologues?

Nope and nope. While Williams had indeed spoken those words, they had actually stemmed from the collective imagination of the writers of August Rush, a 2007 film in which Williams had played a supporting role—that of Wizard, a homeless musician who teaches music to homeless kids. I’ve never seen the picture, and probably won’t, but can you (you—I’m talking to you, someone who digs music enough to not just listen to it, but to read about it, as well) think of a more exquisite expression of music as energy, as something palpable and electric, something that floats or flies or speeds through the air, into the ears, on its way to the heart?

(It’s the same electricity Williams brought to comedy, to being Robin Williams. That he died by his own hand is not as deflating or surprising as it is amazing that he was able to live for 63 years while harnessing that electricity and keeping his darkness at bay. Anyone with that much juice coursing through his brain is the true equivalent of lightning in a bottle; everything stays eternally amazing as long as the glass holds.)

That energy is present in spades in the timbre of Sturgill Simpson’s voice at the end of the ballad ”The Promise,” when he hits the upper corners of his range, and he sounds less like simply one of Waylon’s children, and more like the first country artist I’ve heard in years who actually matters, who isn’t so attracted to beaches, butts, and bottles of Corona that he whizzes on the graves of people like Waylon and Hank Sr. and Lefty and Johnny and others who built the genre that has morphed so disappointingly into the arena-filling kegger accompaniment it currently is.

That energy is present in spades in the timbre of Sturgill Simpson’s voice at the end of the ballad ”The Promise,” when he hits the upper corners of his range, and he sounds less like simply one of Waylon’s children, and more like the first country artist I’ve heard in years who actually matters, who isn’t so attracted to beaches, butts, and bottles of Corona that he whizzes on the graves of people like Waylon and Hank Sr. and Lefty and Johnny and others who built the genre that has morphed so disappointingly into the arena-filling kegger accompaniment it currently is.

The rest of Metamodern Sounds in Country Music is likewise fresh and refreshing, even as Simpson mines familiar aural territory (shuffles and ballads and high, lonesome pedal steel), and incorporates some oddly psychedelic flourishes. Lyrically, he does the same, filling the record with heartbreak and redemption stories, as would any true country artists worth his twang, while mixing in the occasional paean to psychotropic drugs and the visions they beget (the amazing ”Turtles All the Way Down,” one of the great songs released in any genre this year).  It’s an utterly beguiling, ultimately rewarding record.

It’s an utterly beguiling, ultimately rewarding record.

The energy of music is present in the way Bob Mould fills Beauty and Ruin with reminders of every career milestone he’s blasted past in 30 or so years, from the HÁ¼sker-whirl punk of ”Hey Mr. Grey” to the Sugary pop of ”I Don’t Know You Anymore,” to the brooding slabs of sound in ”Low Season.” Listening to the album the first time reminded me of my initial tour through Warehouse: Songs and Stories as a high school senior, followed by the moody acoustic feast of Workbook two years later—it’s a slow-motion whiplash, from soft to loud to really, really loud. Long may he run.

Speaking of blasts from the past—Jesus, where did Tom Petty’s Hypnotic Eye come from? A time machine? H.G. Wells couldn’t have come up with a more implausible scene than the one of me, driving up Highway 1 in Delmarva the first week in August, singing along with ”Fault Lines” and ”Red River” and ”U Get Me High” and ”Full Grown Boy,” everything blasting out of my RAV-4 like I used to blast Southern Accents and Let Me Up (I’ve Had Enough) out of my T-Bird back in high school. I had given up on Petty after The Last DJ and Highway Companion and three-quarters of Mojo, convinced he was stuck in the slow lane that leads to the rock equivalent of the Hollenbeck Palms. So glad he and Benmont and Mike and Ron aren’t quite ready for walkers and soft food yet.

Speaking of blasts from the past—Jesus, where did Tom Petty’s Hypnotic Eye come from? A time machine? H.G. Wells couldn’t have come up with a more implausible scene than the one of me, driving up Highway 1 in Delmarva the first week in August, singing along with ”Fault Lines” and ”Red River” and ”U Get Me High” and ”Full Grown Boy,” everything blasting out of my RAV-4 like I used to blast Southern Accents and Let Me Up (I’ve Had Enough) out of my T-Bird back in high school. I had given up on Petty after The Last DJ and Highway Companion and three-quarters of Mojo, convinced he was stuck in the slow lane that leads to the rock equivalent of the Hollenbeck Palms. So glad he and Benmont and Mike and Ron aren’t quite ready for walkers and soft food yet.

Petty’s aesthetic stepchildren made some pretty great music this year, too. If Ryan Adams and the Hold Steady’s Craig Finn don’t have a mutual admiration society going, someone needs to set them up on a blind date or something. Adams’ self-titled record showcases his range as well as anything he’s done in the last decade. ”Gimme Something Good,” bristles with all kinds of energy, and ”My Wrecking Ball” brings back that sad almost-whisper of a love song that has been his great strength all these years. Side B starts with ”Stay with Me,” which is such an Eighties rock radio production, it sounds like Patty Smyth coulda-shoulda been singing it, and coulda-woulda done a fine job with it. ”Tired of Giving Up” sounds like his turn-of-the-millennium stuff, which is welcome, indeed, and ”Let Go” closes the record with a sigh of resignation and a middle eight that could bring tears to your eyes, if you’re not on your guard.

Petty’s aesthetic stepchildren made some pretty great music this year, too. If Ryan Adams and the Hold Steady’s Craig Finn don’t have a mutual admiration society going, someone needs to set them up on a blind date or something. Adams’ self-titled record showcases his range as well as anything he’s done in the last decade. ”Gimme Something Good,” bristles with all kinds of energy, and ”My Wrecking Ball” brings back that sad almost-whisper of a love song that has been his great strength all these years. Side B starts with ”Stay with Me,” which is such an Eighties rock radio production, it sounds like Patty Smyth coulda-shoulda been singing it, and coulda-woulda done a fine job with it. ”Tired of Giving Up” sounds like his turn-of-the-millennium stuff, which is welcome, indeed, and ”Let Go” closes the record with a sigh of resignation and a middle eight that could bring tears to your eyes, if you’re not on your guard.

The latest Hold Steady record, Teeth Dreams, kinda came and went, and I’m not sure why. To these ears, it’s a better record than Heaven is Whenever or Craig Finn’s solo album. No one chronicles the misadventures of club kids and the borderline drunks who love them quite like Finn. My favorite opening lines of the year might be the ones that start ”Spinners”: ”Before she figures out what’s wrong / Put another record on / She picks it up and she carries the cross / Heartbreak hurts but you can dance it off.” Not sure if Finn has ever written a more Finn-like opening—as Mould populated Beauty and Ruin with fresh reminders of past glories, Craig Finn draws a neat composite of his finest characters and, in so doing, nails his best narrator voice, as well. Additionally, ”Almost Everything” might be the finest use of 12-string acoustic guitar and reverb this year, and if ”Wait a While” hasn’t had crowds bouncing in place since Teeth Dreams dropped, I’m not sure what will do the trick. Most nights, this is the best rock band on the planet, and their album deserved a better fate than it received.

The latest Hold Steady record, Teeth Dreams, kinda came and went, and I’m not sure why. To these ears, it’s a better record than Heaven is Whenever or Craig Finn’s solo album. No one chronicles the misadventures of club kids and the borderline drunks who love them quite like Finn. My favorite opening lines of the year might be the ones that start ”Spinners”: ”Before she figures out what’s wrong / Put another record on / She picks it up and she carries the cross / Heartbreak hurts but you can dance it off.” Not sure if Finn has ever written a more Finn-like opening—as Mould populated Beauty and Ruin with fresh reminders of past glories, Craig Finn draws a neat composite of his finest characters and, in so doing, nails his best narrator voice, as well. Additionally, ”Almost Everything” might be the finest use of 12-string acoustic guitar and reverb this year, and if ”Wait a While” hasn’t had crowds bouncing in place since Teeth Dreams dropped, I’m not sure what will do the trick. Most nights, this is the best rock band on the planet, and their album deserved a better fate than it received.

Beck’s Morning Phase did not suffer from indifference when it was released back in February—the plaudits and huzzahs showered down upon it immediately. And with good reason—it’s a thing of beauty, one of those hazy sunup, coastal drive records that could only have emerged from California. I hear echoes of Surf’s Up and Pacific Ocean Blue and The Notorious Byrd Brothers and Workingman’s Dead, as much as I do Sea Change or Mutations. A beautiful, layered piece of old-school Cali pop record making, Morning Phase began the year with a hefty dollop of hope; it was a record I returned to for months, when I needed a bit of that hope.

Beck’s Morning Phase did not suffer from indifference when it was released back in February—the plaudits and huzzahs showered down upon it immediately. And with good reason—it’s a thing of beauty, one of those hazy sunup, coastal drive records that could only have emerged from California. I hear echoes of Surf’s Up and Pacific Ocean Blue and The Notorious Byrd Brothers and Workingman’s Dead, as much as I do Sea Change or Mutations. A beautiful, layered piece of old-school Cali pop record making, Morning Phase began the year with a hefty dollop of hope; it was a record I returned to for months, when I needed a bit of that hope.

Much was expected of Beck, and he delivered. I expect a great deal of the Felice Brothers, and the last studio record they made, 2011’s strange, noisy Celebration, Florida, was an enormous disappointment—a Neither Fish Nor Flesh-sized disappointment; a Phantom Menace-sized disappointment. They redeemed themselves somewhat with God Bless You, Amigo, an odds-and-sods collection of covers and unreleased originals that was great, rollicking fun—just the way I like em. But that seemed less an album than a very cool playlist, partly because it was disjointed and partly because it was released online only (a five-dollar download, meant to raise money to replace the band’s touring vehicle).

Favorite Waitress is an honest-to-Gawd album, and a fine one at that. Whether it’s the languid ”Saturday Night” or the silly roll of ”Cherry Licorice,” or the herky-jerky stumble of ”Katie Cruel,” the band keeps the music loose, the harmonies on point, and the sense of fun intensely palpable. And if there’s any cosmic justice in this world, the album-opening ”Bird on a Broken Wing” will join older tracks like ”Frankie’s Gun!” as a staple of the Felice Brothers’ live sets, one of those songs they can’t leave the building without playing.

Favorite Waitress is an honest-to-Gawd album, and a fine one at that. Whether it’s the languid ”Saturday Night” or the silly roll of ”Cherry Licorice,” or the herky-jerky stumble of ”Katie Cruel,” the band keeps the music loose, the harmonies on point, and the sense of fun intensely palpable. And if there’s any cosmic justice in this world, the album-opening ”Bird on a Broken Wing” will join older tracks like ”Frankie’s Gun!” as a staple of the Felice Brothers’ live sets, one of those songs they can’t leave the building without playing.

Favorite Waitress marked the full-on return of a band I love and very much needed to hear new music from. I didn’t realize I needed to hear Lydia Loveless, until hearing Somewhere Else the first time, and confirming the need with listens 2 through however many dozen I’ve gone through in the last months. The punky twang in her voice is perhaps the perfect nuance, the ultimate tool to put across the sadness and defiance in her songs, the confidence and apprehension that sometimes comes through in the same song. Throughout the record, she’s strong enough to make demands of her lover, vulnerable enough to pine for him when he’s gone; confident enough to find her own escape, wherever she wants, with whatever she wants; aware enough to embrace regrets.

Those regrets come through with devastating effect in the album’s first two songs, ”Really Wanna See You” and ”Wine Lips.” The former is a rocking take on an evening when a little curiosity, mixed with a little chemical indulgence, leads to a phone call to an old lover, a ”just checking in” talk that should never have taken place. ”Wine Lips” is all about the conversation that led to the breakup (”That’s all I really wanna do / Is be somebody that you can talk to / … But I went too far like I always do”), or maybe the one that follows the phone call and the awkward meeting afterward.

But then you have Side Two’s ”Head,” which turns the verses’ desperation (”I need you more than I ever let on”) into a lovely, filthy chorus (”Don’t stop get in my bed / And baby don’t stop giving me head”) whose sentiment she can only express to her lover in her dreams. Perhaps that’s the best she can hope for, maybe the reality of the situation is the full-on conflict described in ”Verlaine Shot Rimbaud,” where the voice issues threats both veiled and unveiled (”Don’t have to kick nobody out of the house / They can stick around and watch us duke it out”). And in an odd yet inspired choice, Loveless closes the album with a cover of Kirsty MacColl’s ”They Don’t Know,” a perfect rendering of the tragic songwriter’s most lasting creation, divorced from the girl-group sweetness of its most popular version, and given the strong yet wounded voice it has always deserved.

But then you have Side Two’s ”Head,” which turns the verses’ desperation (”I need you more than I ever let on”) into a lovely, filthy chorus (”Don’t stop get in my bed / And baby don’t stop giving me head”) whose sentiment she can only express to her lover in her dreams. Perhaps that’s the best she can hope for, maybe the reality of the situation is the full-on conflict described in ”Verlaine Shot Rimbaud,” where the voice issues threats both veiled and unveiled (”Don’t have to kick nobody out of the house / They can stick around and watch us duke it out”). And in an odd yet inspired choice, Loveless closes the album with a cover of Kirsty MacColl’s ”They Don’t Know,” a perfect rendering of the tragic songwriter’s most lasting creation, divorced from the girl-group sweetness of its most popular version, and given the strong yet wounded voice it has always deserved.

That voice is what keeps drawing me back to this wonderful album, my favorite of all the music I’ve heard this year. It’s a voice reminiscent of Nanci Griffith’s, Maria McKee’s, Shelby Lynne’s, and others—voices I discovered years ago when I least expected to, but when I most needed to hear them.

There were other really good records released this year—more than usual, now that I think of it—though I was not able to obtain them in spinning black circle format, for whatever reason. Among them … The Australian duo Luluc released an exquisite debut, Passerby, that I discovered quite by chance; the stillness of the record is as calming as it is haunting. Lucinda Williams put out a double album, Down Where the Spirit Meets the Bone, the second disc of which is as good as anything I’ve heard from her in 15 years. Annie Clark is my choice for Artist of the Year, as the self-titled St. Vincent record and the performances that followed revealed her to be a straight-up rock star, which I suppose she’s always kinda-sorta been—a fully formed and supremely confident writer, performer, and guitarist.

I’ll share three more great moments in vinyl from 2014. The first is something of an amalgam of moments—great crate-digging finds. My roll call of glory this year includes Duane & Greg Allman [sic], a 1972 issue of the Allmans’ work with their early band The 31st of February; it includes an early take on ”Melissa,” that sweetest of Allmans ballads.  I’d been looking for it for years. I’d also looked for an affordable copy of Sandinista!, the Clash’s dense, difficult, awesome 3-LP set from 1981, and I finally found one this year—on my birthday, of all days. And, perhaps most miraculously, a recent trip to my favorite record store yielded a clean copy of Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely, which had been on my wish list for as long as I’ve had a wish list. That sad, beautiful record now sits comfortably on my shelves, with the 30 or so other Sinatras I’ve found and enjoyed over the years.

I’d been looking for it for years. I’d also looked for an affordable copy of Sandinista!, the Clash’s dense, difficult, awesome 3-LP set from 1981, and I finally found one this year—on my birthday, of all days. And, perhaps most miraculously, a recent trip to my favorite record store yielded a clean copy of Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely, which had been on my wish list for as long as I’ve had a wish list. That sad, beautiful record now sits comfortably on my shelves, with the 30 or so other Sinatras I’ve found and enjoyed over the years.

A second great moment came back in July, when in my mail, I found a package from my brother from another mother, Matt Wardlaw. Santa Matt gifted me with a vinyl copy of Night Ranger’s most recent record, High Road—one of a limited number of vinyl editions available. I am a child of the Eighties—an arena rock-loving child of the Eighties—and the band’s music connects me to a fondly recalled period in my life, a happy headspace to which I return when this often-overrated adult thing gets me down. High Road hearkens back to the sound and spirit of Midnight Madness and 7 Wishes, my two favorite Night Ranger records, both of which still get mad spins on ye olde turntable. To be able to play new songs like ”I’m Coming Home,” ”Hang On,” and ”Only for You Only” on that same turntable is a pleasure for which I am quite grateful, just as I am grateful for friends like Matt, whose generosity moves me more than I can adequately express.

A second great moment came back in July, when in my mail, I found a package from my brother from another mother, Matt Wardlaw. Santa Matt gifted me with a vinyl copy of Night Ranger’s most recent record, High Road—one of a limited number of vinyl editions available. I am a child of the Eighties—an arena rock-loving child of the Eighties—and the band’s music connects me to a fondly recalled period in my life, a happy headspace to which I return when this often-overrated adult thing gets me down. High Road hearkens back to the sound and spirit of Midnight Madness and 7 Wishes, my two favorite Night Ranger records, both of which still get mad spins on ye olde turntable. To be able to play new songs like ”I’m Coming Home,” ”Hang On,” and ”Only for You Only” on that same turntable is a pleasure for which I am quite grateful, just as I am grateful for friends like Matt, whose generosity moves me more than I can adequately express.

If I had to point to one moment in my listening year that gave me the greatest joy as a music lover and vinyl collector, though, I would point to the evening in September when I sat down to listen to the new mono remasters of the first four Beatles records—Please Please Me, With the Beatles, A Hard Day’s Night, and Beatles for Sale. It was something of an extravagance, buying four of them, but I’d held off on getting these four when the stereo remasters were released in 2012, because I wanted to hear them as the band had intended them to be heard, in clear, unadulterated, monophonic sound, not stereofied or channel-separated, minus any overt technical skullduggery.

The packaging is beautiful, the vinyl heavy and high-quality, and the sound as immediate and moving as I had hoped. For the 90 or so minutes I spent on the first listen through them, I was transported to the moments of their release, and even with 50 years of cultural import between back then and right now, I understood. I got it. I heard what kids heard back then, what my parents must have heard—all the vitality and sweetness and pure dynamic teenage energy. It was that purity that got me—whether it was really there, or whether it was something I projected onto what I heard, I don’t know; I’d like to think the former. But every chord, every solo, every beat, every note and word and ”Whoo!”—it all resonated with me in clear, uncluttered moments of absolute joy.

The packaging is beautiful, the vinyl heavy and high-quality, and the sound as immediate and moving as I had hoped. For the 90 or so minutes I spent on the first listen through them, I was transported to the moments of their release, and even with 50 years of cultural import between back then and right now, I understood. I got it. I heard what kids heard back then, what my parents must have heard—all the vitality and sweetness and pure dynamic teenage energy. It was that purity that got me—whether it was really there, or whether it was something I projected onto what I heard, I don’t know; I’d like to think the former. But every chord, every solo, every beat, every note and word and ”Whoo!”—it all resonated with me in clear, uncluttered moments of absolute joy.

Something tells me it will be a long time before I experience something that again in a record, if I ever do. But there’s always hope, and hope is what keeps me coming back, keeps me clinging to the power of music, to the energy of it, to that harmonic connection between us all, as Robin Williams’ character so eloquently put it. He knew it; the Beatles knew it; Lydia Loveless and Bob Mould and Beck and the rest know it.

We know it, too—you and I and those closest to us who hear what we listen to, who engage in (or maybe endure) a hundred or three hundred conversations about these sounds and what they mean to us. It’s something to be grateful for, this connection, this energy.

Let us raise a toast to 2014’s sounds, and whisper a word or two of hope for 2015.

Comments