If there’s an American composer whose catalog has long been crying out for musical-theater treatment, it’s Randy Newman. He creates vivid characters whose stories require only a few minutes in the telling, yet whose impact has reverberated over the decades — the seductive slaveship captain of ”Sail Away,” the mocking God of ”That’s Why I Love Mankind,” the neglectful husband of ”Marie,” the unrepentant segregationist of ”Rednecks” … and, most recently, the similarly unrepentant warmongers and torturers of ”A Few Words in Defense of Our Country.” On record, Newman has tackled even the vilest of these characters in his own distinctive voice, not fearing the consequences of (to name just one example) scaling the pop charts with a tirade against ”Short People.”

If there’s an American composer whose catalog has long been crying out for musical-theater treatment, it’s Randy Newman. He creates vivid characters whose stories require only a few minutes in the telling, yet whose impact has reverberated over the decades — the seductive slaveship captain of ”Sail Away,” the mocking God of ”That’s Why I Love Mankind,” the neglectful husband of ”Marie,” the unrepentant segregationist of ”Rednecks” … and, most recently, the similarly unrepentant warmongers and torturers of ”A Few Words in Defense of Our Country.” On record, Newman has tackled even the vilest of these characters in his own distinctive voice, not fearing the consequences of (to name just one example) scaling the pop charts with a tirade against ”Short People.”

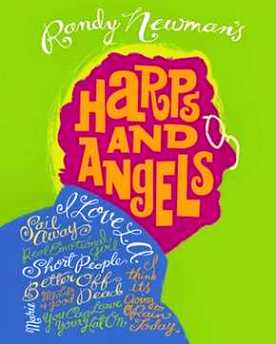

Even as his fans admire that courage, theatrical producers have long imagined the potential in creating a show that brings his miniature dramas to life. A few have tried before — the La Jolla Playhouse staged a revue called Maybe I’m Doing It Wrong in 1983, and South Coast Repertory produced The Education of Randy Newman in 2000 — and, of course, Newman took his own shot at a theatrical song cycle with Faust 15 years ago. Now, here comes the latest attempt: Harps and Angels, whose world-premiere engagement opened on Sunday at L.A.’s Mark Taper Forum. It boasts some prominent names — director Jerry Zaks, and performers including Michael McKean, Katey Sagal and Tony winner Adriane Lenox — and some big ambitions for the future. That said, its creators wisely have chosen not to impose extravagant staging or too much musical bombast, and instead are allowing Newman’s characters to speak largely for themselves.

”Conceiver” (as he’s described in the program) Jack Viertel has achieved much in the theater on both coasts over a long career, but for our purposes his most significant credit is the 1995 Lieber & Stoller revue Smokey Joe’s CafÁ©. That show, though never a huge hit in its own right, helped launch the ”jukebox musical” concept (for better or worse). And while its descendants like Mamma Mia and Jersey Boys layered plots and dialogue atop their scores of beloved pop classics, with Harps and Angels Viertel and Zaks (who directed SJC as well) have stuck to their original script … which is to say, no script at all. Just the songs, offered up with enough costuming, props and attitude to place them in a loosely theatrical context.

”Conceiver” (as he’s described in the program) Jack Viertel has achieved much in the theater on both coasts over a long career, but for our purposes his most significant credit is the 1995 Lieber & Stoller revue Smokey Joe’s CafÁ©. That show, though never a huge hit in its own right, helped launch the ”jukebox musical” concept (for better or worse). And while its descendants like Mamma Mia and Jersey Boys layered plots and dialogue atop their scores of beloved pop classics, with Harps and Angels Viertel and Zaks (who directed SJC as well) have stuck to their original script … which is to say, no script at all. Just the songs, offered up with enough costuming, props and attitude to place them in a loosely theatrical context.

Viertel says he devised the show’s structure after hearing the song ”Harps and Angels” itself, which served as the title track for Newman’s most recent studio album. It’s sung from the perspective of an older man who’s had a brush with mortality … and it made Viertel recall the track ”Dixie Flyer,” a childhood-recalling track from Newman’s 1988 album Land of Dreams. Placing the latter song near the beginning and the former near the end, Viertel and Zaks give the show a vaguely autobiographical framework; Newman himself pitches in (via video) with a few choice nuggets of reminiscence and wisdom. This attempt at a through-line doesn’t really work, unless one views the show’s parade of characterizations as different facets of Newman’s own persona. But the thematic flimsiness hardly matters, because his songs are rapturous enough to support the show on their own merits.

The video clips are Newman’s only direct contribution to the show; the heavy lifting is left to a terrific band and a cast of six, three men and three women. For the most part, they’re up to the task. In addition to tackling those contextualizing songs, McKean gets many of the revue’s showiest moments, from suggesting that America ”drop the big one” (a line from the classic ”Political Science”) to a turn as a glitzy cowboy in ”Big Hat, No Cattle”; he also gets to play the curmudgeon of ”Short People.” Lenox, so riveting as the brutally honest mother in Doubt on Broadway a few years back, here turns ”Louisiana 1927″ into a showstopper, but makes her biggest impact when her presence is least expected. She steps out of the shadows to provide ironic harmonies at the climax of ”Sail Away”; later she appears in the rafters, dressed in angelic white, to spit out the venomous ”God’s Song” (”How we laugh up here in heaven, at the prayers you offer me!”).

The video clips are Newman’s only direct contribution to the show; the heavy lifting is left to a terrific band and a cast of six, three men and three women. For the most part, they’re up to the task. In addition to tackling those contextualizing songs, McKean gets many of the revue’s showiest moments, from suggesting that America ”drop the big one” (a line from the classic ”Political Science”) to a turn as a glitzy cowboy in ”Big Hat, No Cattle”; he also gets to play the curmudgeon of ”Short People.” Lenox, so riveting as the brutally honest mother in Doubt on Broadway a few years back, here turns ”Louisiana 1927″ into a showstopper, but makes her biggest impact when her presence is least expected. She steps out of the shadows to provide ironic harmonies at the climax of ”Sail Away”; later she appears in the rafters, dressed in angelic white, to spit out the venomous ”God’s Song” (”How we laugh up here in heaven, at the prayers you offer me!”).

Sagal may still be best known as Peg Bundy, but before that she spent years as one of Bette Midler’s ”Harlettes,” and more recently she has shown off her vocal chops in well-received cabaret engagements. Here she is the world-weary narrator of ”Gainesville” and other songs, and she gets the unenviable task of making the Bush administration’ bumbling and arrogance seem logical on the show-closing ”A Few Words in Defense of Our Country.”

Elsewhere in Act Two, McKean, Storm Large (a hot, blonde rocker chick) and Ryder Bach (a nebbishy twentysomething) explore the thin line between desire and degradation during an entrancing pas de trois. First, a desperate McKean can’t get a scantily clad, writhing Large to look his way while he debases himself on ”A Fool in Love”; then Large turns the tables on a drooling Bach, ordering the striptease of ”You Can Leave Your Hat On.” Hunky Matthew Saldivar gets a couple of terrific moments as well, dismissing Large as ”A Real Emotional Girl,” playing the bad husband of ”Marie” as a drunk, and slithering his way through the simultaneously supercilious and defensive ”My Life Is Good.”

Occasional lapses in pacing plague the show, and not every song gets its due — Lenox’s version of ”When She Loved Me,” from Toy Story 2, is a bit perfunctory, and Bach speeds his way through the hilarious ”I Gotta Be Your Man.” Inevitably, one views the lineup of songs and quickly spots what’s missing (”I Want You To Hurt Like I Do,” from Land of Dreams, topped my wish list). Most importantly, the song choices include too few upbeat tunes, to the point where the cast resorts to flogging ”I Love L.A.” not once, but twice. The show could use at least one more genuine crowd-pleaser, like ”Mama Told Me Not To Come,” whose absence is glaring.

Occasional lapses in pacing plague the show, and not every song gets its due — Lenox’s version of ”When She Loved Me,” from Toy Story 2, is a bit perfunctory, and Bach speeds his way through the hilarious ”I Gotta Be Your Man.” Inevitably, one views the lineup of songs and quickly spots what’s missing (”I Want You To Hurt Like I Do,” from Land of Dreams, topped my wish list). Most importantly, the song choices include too few upbeat tunes, to the point where the cast resorts to flogging ”I Love L.A.” not once, but twice. The show could use at least one more genuine crowd-pleaser, like ”Mama Told Me Not To Come,” whose absence is glaring.

As with Smokey Joe’s CafÁ©, the question that hangs over Harps and Angels’ future prospects is whether it has enough theatrical substance to meet the expectations of Broadway audiences. Newman’s songs have the dramatic gravitas, to be sure, and the performances here are mostly terrific; still, with its simple sets, lack of script and flimsiness of theme, the show sits in that uncomfortable middle ground between a cabaret act and a full-blown musical. Can it succeed at Broadway ticket prices? Perhaps not — but it has terrific potential at one of the bigger Off-Broadway houses, or perhaps at a venue like the onetime Studio 54 or New World Stages (where Cabaret and Rock of Ages, respectively, had so much success).

Harps and Angels may settle into a future as one of those TKTS specials — a show that lingers in part because of its rotating array of B-list celebrity stars (”joining the cast for three weeks only: American Idol Kris Allen!”) and its perpetual last-minute availability at the half-price booth. It may not be quite the fate that Newman’s music deserves, but maybe the show can keep his songs in front of audiences (and the publishing royalties rolling in) while the man eases toward retirement. There’s something to be said for that; after all, Newman wrote ”It’s Money That Matters” and ”It’s Money That I Love” … and maybe he was singing those songs as himself.

Comments