I just got back from the desert, and chances are, you know someone else who has as well. It’s taken 25 years for Black Rock City to become a major destination for people worldwide the week before Labor Day, but it’s become so popular that the proverbial doors to that seemingly endless open desert closed before the end of July this year. For the procrastinators and indecisive types who had still yet to buy a ticket to the dust, news of the sell-out hit hard. Many wondered how a place as vast and desolate as the high Nevada desert could possibly reach capacity and most thought additional tickets would somehow be released. But there weren’t, and it was no matter: Burning Man indeed sold out. For the first time ever.

I just got back from the desert, and chances are, you know someone else who has as well. It’s taken 25 years for Black Rock City to become a major destination for people worldwide the week before Labor Day, but it’s become so popular that the proverbial doors to that seemingly endless open desert closed before the end of July this year. For the procrastinators and indecisive types who had still yet to buy a ticket to the dust, news of the sell-out hit hard. Many wondered how a place as vast and desolate as the high Nevada desert could possibly reach capacity and most thought additional tickets would somehow be released. But there weren’t, and it was no matter: Burning Man indeed sold out. For the first time ever.

Like others, I questioned whether the tickets running out signified that the fringe festival founded on renegade principles had at last staked a claim on the global mainstream consciousness. I’m not convinced that it means anything at all really, other than giving truth to the notion that most really cool things end up getting really popular eventually. Does the fact that major media outlets like The New York Times and Wall Street Journal have published numerous articles about Burning Man mean it’s truly become a cultural phenomenon? When any niche event gets that large, does it inevitably lead to a collective fear in the degradation of the event’s quality?

Does the rise in attendance symbolize a shift in the public embrace of counterculture, and could it be at all politically motivated in these years of growing national discontent? Does it signify emerging popularity in electronic music, innovations in camping equipment, greater ease and affordability of travel, or suggest anything about our ability to impact one another with increasingly better and cheaper digital cameras and greater volumes of blog posts?

Does it mean anything other than the world is filling up with people and pain, and Black Rock City represents a bastion of well-intended (and open-armed) hedonism?

Who knows. Who really cares. But I’m compelled to ask these questions because more than ever, I’m finding it impossible to ignore the ubiquity of the Burning Man culture, especially as a resident of San Francisco. The event was started at Baker Beach in 1986, and the city noticeably deflates more and more each year during the festival, when high-powered Google execs and tech wunderkinds, hard partiers and local artists, famously make the pilgrimage to Black Rock City only to come back and marvel to their friends and coworkers about the crazy shit they saw out there under a glowing moon in the depths of the desert.

So yeah, the Burning Man lore lures many of us out there eventually. But allow me to make this disclaimer: I am no expert or hardcore Burner. I barely knew anything about the thing until I moved out to the Bay Area seven years ago, and even then it took me until 2009 to get there.

I loved (and very slightly loathed) my first experience. It’s hard in the desert. I was intimidated by the elements and discouraged by some of the rules. But I was deeply moved by those days I spent in Black Rock City. I was confronted and challenged and had fun beyond words. I knew I needed to go back, beyond the scope of novelty, to really study and celebrate the human creativity and community that takes shape out there in a vast and shifting landscape—a landscape that I initially cursed and foreswore but now, having just gotten back for my second time, appreciate and actually kind of love.

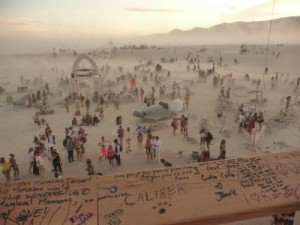

Now I understand the necessity of the Burn being held nowhere other than the Black Rock desert. Without that open space and gigantic sky, lending itself to soft twilights over an expansive cracked floor, it wouldn’t feel so… surreal. It feels like 50,000 humans have colonized on Mars or the Moon, the celestial matter of the setting changing with the light of day.

So here I am now, two years later, sitting on the couch in my apartment in San Francisco, looking at my pile of dust covered clothes and camping equipment and still finding it difficult to articulate the Burning Man experience. I could probably write 20,000 words before midnight strikes, and I still couldn’t capture it appropriately.

If there is one singular thing that everyone seems to agree on, it’s that Burning Man is impossible to explain in words.

Sure, any sentiment is fairly impossible to describe to someone who’s never shared in said sentiment firsthand, especially when it’s as visceral as this one. But it’s also difficult to articulate because Burning Man is an individual experience—it is disparate lone souls that make up a community that fosters and celebrates self-expression. Let’s face it: The communities in which most of us find ourselves do not generally grant us the space or right or time to express ourselves in such a blatant and radical manner. Using Burning Man as the lens and the organized vehicle to bring together people from all over the globe, the week-long festival enables those who let it explore new and novel ways of considering the art, community, and creativity that surrounds them—and all while being responsible for his or her own survival in Black Rock City. ”Radical self-reliance,” they call it. You’re reveling with 50,000 other people, but to get the most out of the dust, you have to conquer it alone.

For all its glory, I find Burning Man to be immensely polarizing, and it carries a stigma of drugs/bad music/indulgence/overexposure/pretension. And I bet nowhere is that divisiveness more apparent than it is in the Bay Area. With the most concentrated Burner culture and largest population of attendees, San Francisco is a land of extreme localities and divergent neighborhood culture; what one demographic loves, the same one hates. San Francisco taught me that Burning Man is definitely not for everyone.

So for the haters, of which there are many, and the doubters, of which there are more, with just two years under my belt, I do know this: Burning Man takes on whatever form you want it to. You have to relinquish yourself to its spirit but keep your focus intact.

And if you do, the possibilities are nearly endless.

Among the kinds of people I’ve discovered on the playa: Wizened grandparents in their 80s with binoculars around their necks. Yogis and spiritual healers, elementary school teachers, ex-pat nomads, suburban yuppies who left their five kids at home. A Dutch man in his 40s flew out with his 12-year-old son. Billionaire CEOs and world famous architects alongside club kids and frat boys and pagan hippies and steam punks and bluegrass musicians and sculptors and beautiful girls in beautiful costumes. Travelers from Japan, Lebanon, Kenya, New Zealand, Mexico, France… many of them there alone.

You will meet fascinating strangers, different from you in almost every way. You can also find a kindred spirit or two.

Each of those 50,000 attendees uncovers their own jewels and apparitions in the dust. You can be rendered speechless from the most thought-provoking piece of art you’ll ever see. You will get caught in a dust storm. You can feel overwhelmed. You will be sweltering hot and then cold as ice 10 hours later. You will lose your friends for hours and see the sunrise alone. You can ride your bike into a 30 foot statue. You can trip over a door to nowhere. You can climb a ladder to the sky and stare at the horizon. You will probably sleep in earplugs.

You will dance to some of the world’s best sound systems, at stages that arc the esplanade and blast among the best electronic music around. You will chase after mobile sound systems that light up and patrol the strange landscape like giant bleeping insects.

You will see pink clouds fleeting and a crescent moon rise. You will see shooting stars and watch midnight skydivers fall to earth with tails that look like comets.

You will see pink clouds fleeting and a crescent moon rise. You will see shooting stars and watch midnight skydivers fall to earth with tails that look like comets.

You can gawk at a guy in a full-piece rubber chicken suit dancing under a relentless sun. You can zipline and back flip on trampolines and watch spinning orbs through 3D glasses.

You can get drunk and sunburned. You can party completely sober, and be fed every meal by a neighbor. You will be served hot chai tea at 5am under a red tent while watching aerial silk dancers descend from the ceiling and bend into unfathomable shapes.

You can attend a gathering of academics discussing engineering marvels, and see groups of runners complete 5ks—and even 50ks—in the heat of the afternoon.

You will see lots of fire. People shooting it, dancing with it, fanning it, extinguishing it. You will watch a human effigy burn and a primal jubilation come over an enormous crowd in the celebration of destruction.

You will see people cry and pray and memorialize their loved ones before a 45,000 square foot temple… and then they will reduce the structure to ash.

You will feel somber, and you will feel elated.

Extreme, right?

Point is, everything under the sun comes together under that sun to coexist in a commerce-free society of communal love and acceptance for one week in a place where time goes unchecked as the day blazes mercilessly and the night fades to dawn. The world seems so much bigger there, and so much smaller. It’s exhausting and invigorating, charged by the extreme polarities present in both nature and the human spirit.

acceptance for one week in a place where time goes unchecked as the day blazes mercilessly and the night fades to dawn. The world seems so much bigger there, and so much smaller. It’s exhausting and invigorating, charged by the extreme polarities present in both nature and the human spirit.

And the more people that go to Burning Man each year and the earlier the tickets sell out… will that change it? I don’t know. I don’t think so. The individual has complete control over his or her experience, so as long as your ticket is in hand and you respect the land, you will not leave the playa the same person who entered.

It may not be the place or experience you’re looking for. But for the thousands of people that have found their way to the high Nevada desert over the past 20-plus years, it represents a utopian ideal and gives truth to possibility. So whether you love it, loathe it, or dismiss it, Burning Man has made an impact. And that’s impossible to ignore.

Comments