A number of years ago, Counting Crows front man/Hair Club for Rastafarians client Adam Duritz tossed up a cool blog post about his adolescent search for records he’d read about but had had difficulty finding. This was in the early Eighties, when not only oddball (in the U.S.) stuff like Modern Lovers, Big Star, and Fairport Convention were nigh impossible to locate, but also classic records like the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, which had actually gone out of print for a while.

A number of years ago, Counting Crows front man/Hair Club for Rastafarians client Adam Duritz tossed up a cool blog post about his adolescent search for records he’d read about but had had difficulty finding. This was in the early Eighties, when not only oddball (in the U.S.) stuff like Modern Lovers, Big Star, and Fairport Convention were nigh impossible to locate, but also classic records like the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, which had actually gone out of print for a while.

Back in the day, records just did that; they’d be around for a while and either not sell, or sell out of their pressing, and poof—they’d be gone. Before the commercial advent of the compact disc, when the record industry made a mint reissuing collectible gems in the new format (as well as compelling listeners re-purchase the bulk of their record collections), stuff just disappeared, and that stuff, if it was any good, could become legend. Duritz had a list of 40 or 50 such records, and spent the bulk of one family vacation in England and Scotland tracking down just about every one. After capping the epic search by finding his holiest of holy grail titles (Thunderclap Newman’s Hollywood Dream), he writes, “I went home the next day and didn’t leave my room for weeks. I just sat there listening to music I’d been dreaming about for years.”

I read a lot about music in my adolescence, and there were a good many records about which I dreamt before ever hearing them. One source of my dream subjects was Rolling Stone issue 507—one of its twentieth anniversary editions from 1987, commemorating the 100 best albums released in the course of the magazine’s run. The issue was full to bursting with decent-sized, well-written reviews on classic records—everything from T.Rex, Captain Beefheart, and the Nuggets compilation, to multiple records by the usual suspects (the Stones, the Beatles, Dylan, etc.).

Dave Marsh and John Swenson —the editors of the first two editions of The Rolling Stone Record Guide—were also big contributors to my scholarship. I read and re-read my copy of the second edition (the blue one, published in 1983) many, many times over. I knew which albums were worthy of a five-star rating (“Indispensable: a record that must be included in any comprehensive collection”), as well as the ones that earned one star, or even zero stars (“Worthless: a record that need never [or should never] have been created. Reserved for the most bathetic bathwater”). The five-star records were things of legend—among them Blonde on Blonde, The Basement Tapes, Blood on the Tracks, Beggars Banquet, Exile on Main Street, Wheels of Fire, Electric Ladyland, At Fillmore East, Plastic Ono Band, Traffic, Astral Weeks, Layla, the White Album, really damned near anything the Beatles put out.

Dave Marsh and John Swenson —the editors of the first two editions of The Rolling Stone Record Guide—were also big contributors to my scholarship. I read and re-read my copy of the second edition (the blue one, published in 1983) many, many times over. I knew which albums were worthy of a five-star rating (“Indispensable: a record that must be included in any comprehensive collection”), as well as the ones that earned one star, or even zero stars (“Worthless: a record that need never [or should never] have been created. Reserved for the most bathetic bathwater”). The five-star records were things of legend—among them Blonde on Blonde, The Basement Tapes, Blood on the Tracks, Beggars Banquet, Exile on Main Street, Wheels of Fire, Electric Ladyland, At Fillmore East, Plastic Ono Band, Traffic, Astral Weeks, Layla, the White Album, really damned near anything the Beatles put out.

(Marsh and Swenson were not, however, particularly kind to my beloved arena rock—the likes of Foreigner, REO Speedwagon, Journey, and Styx garnered a fair share of one- and two-star reviews. That’s a complaint for another time, though).

Once I got my first job, finding and purchasing these albums became a priority, and each time I got two or three of them (rarely just one—I was catching up, after all), I went immediately to my room, put vinyl on turntable and needle on vinyl, and holed up for an hour or two hours or an entire evening, reveling in those sounds, the sounds I was finally experiencing, not just reading about. Those were formative hours for me, hours when my musical interests opened up wide, when the totemic titles I’d imagined, some of them for years, became real, and brought about real responses from me.

The difference between what I’d thought the records would sound like and what I finally encountered was often profound, and profoundly moving. In my abstract imaginings, Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde sounded like a revolution, the cacophonous racket of “Rainy Day Women # 12 & 35” (which I knew from the radio) writ long and deep, with Dylan’s court jester declamations giving voice to mysteries without any obvious solutions. I listened to the album and found those things and more; I was thrown by the sadness of “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” and positively gobsmacked by the side-long “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.” I’d read that Exile on Main Street was bluesy and swaggering and mean, but the thickness of the sound and the authoritative command of the darkness in the songs were a kind of magic I’d never before encountered, not even on other Stones records I’d heard. Astral Weeks was maybe the biggest mind-blower—nothing in my experience as a listener at that point had provided me with the tools to grasp Morrison’s swirling pool of jazz and strings and poetry once I’d heard it. It was nothing like the pastoral calm I’d imagined, and I had no idea what to make of it until I’d listened to it many, many times.

The difference between what I’d thought the records would sound like and what I finally encountered was often profound, and profoundly moving. In my abstract imaginings, Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde sounded like a revolution, the cacophonous racket of “Rainy Day Women # 12 & 35” (which I knew from the radio) writ long and deep, with Dylan’s court jester declamations giving voice to mysteries without any obvious solutions. I listened to the album and found those things and more; I was thrown by the sadness of “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” and positively gobsmacked by the side-long “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.” I’d read that Exile on Main Street was bluesy and swaggering and mean, but the thickness of the sound and the authoritative command of the darkness in the songs were a kind of magic I’d never before encountered, not even on other Stones records I’d heard. Astral Weeks was maybe the biggest mind-blower—nothing in my experience as a listener at that point had provided me with the tools to grasp Morrison’s swirling pool of jazz and strings and poetry once I’d heard it. It was nothing like the pastoral calm I’d imagined, and I had no idea what to make of it until I’d listened to it many, many times.

Which I did back then, to all these records—lots and lots of spins, honoring my anticipation with deep dives into each album, repeated readings of liner notes, appreciative study of the album art or the gatefold. I’d conjured some idea of the work in my mind before needle ever met groovel the experience continued unabated once the thing was playing. CDs provided an approximation of this kind of thing, but their dimensions weren’t up to the task of that talismanic quality I assigned the music they contained.

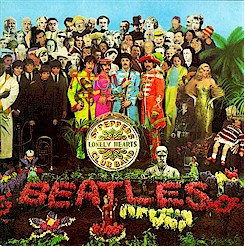

‘Twas not always for lack of trying. In 1987, Capitol issued the bulk of the Beatles’ recorded output (the British versions, at least) on CD. The entire campaign was built around making sure Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was on store shelves in time for its twentieth anniversary on June 1. And what a campaign it was—even an enthusiastic listener such as I got damned tired of seeing/hearing/reading “It was twenty years ago today …” in the lead-up to the disc’s release.

The disc’s package was, for the time, stunning. The iconic cover graced the gorgeous 26-page booklet, full of vibrant color, with cool liner notes and replicas of the humorous cutouts and the funky psychedelic red inner sleeve. There was even a bonus track comprised of the ultra-high-frequency tone and gibberish sound loop held in the run-out groove of the original album.

The disc’s package was, for the time, stunning. The iconic cover graced the gorgeous 26-page booklet, full of vibrant color, with cool liner notes and replicas of the humorous cutouts and the funky psychedelic red inner sleeve. There was even a bonus track comprised of the ultra-high-frequency tone and gibberish sound loop held in the run-out groove of the original album.

Minus the clicks and pops and absent the need to flip the disc over in order to hear the full album, the Sgt. Pepper’s CD was as good as CDs got in the late Eighties, which, as it turns out, was setting the bar pretty low. Though Capitol tried to replicate the playfulness of the original album by including copies of its accoutrements, the sound of the CD was fairly flat, and the package, though generous, was still really … small. Opening it (cutting open the longbox—remember them?—to get to the disc, clasped tightly closed by those silver security stickers whose glue rarely came off cleanly) was significantly dissimilar from opening and holding the LP’s 12×12 cover, examining all those faces on the front, carefully sliding the vinyl out, gently placing it on the turntable, putting on the headphones (Sgt. Pepper’s must be listened to through headphones at some point early in one’s acquaintance with the record), and starting it all up. Leaning back, still looking at those faces, as the fade-in begins on the title track—the voices and tuning instruments coming to the fore, 10 or 12 seconds before the first guitars and drums are heard; the brief intro is played, and McCartney bulls his way in with those words, the ones that annoyed me so in the CD advertisements, but which seem now to be as natural a part of storytelling as “Once upon a time”:

It was twenty years ago today

Sgt. Pepper taught the band to play

They’ve been going in and out of style

But they’re guaranteed to raise a smile

So may I introduce to you

The act you’ve know for all these years

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band

And then his voice gets swallowed up in applause and horns and God knows what else. And you’re off—off on that amazing journey through sound and songs—songs filled with joy and discovery and sadness and fun and humor and abstraction. And drugs—lots of drugs. And yet such precision—every note in its place, every voice lifted in precise melody and harmony, every chiming or ringing sound coaxed out of the guitars, every color wrung from the strings and brass and woodwinds. And sitar—“Within You, Without You” sent my head for a spin, because all the times I had imagined what Sgt. Pepper’s was going to sound like, I never heard sitar or tabla or dilruba in my head, because I’d never heard them outside my head.

And then his voice gets swallowed up in applause and horns and God knows what else. And you’re off—off on that amazing journey through sound and songs—songs filled with joy and discovery and sadness and fun and humor and abstraction. And drugs—lots of drugs. And yet such precision—every note in its place, every voice lifted in precise melody and harmony, every chiming or ringing sound coaxed out of the guitars, every color wrung from the strings and brass and woodwinds. And sitar—“Within You, Without You” sent my head for a spin, because all the times I had imagined what Sgt. Pepper’s was going to sound like, I never heard sitar or tabla or dilruba in my head, because I’d never heard them outside my head.

Certainly, not everything on the record was a surprise; before hearing the album in full the first time, I had been exposed to common touchstones like “With a Little Help from My Friends” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” just from listening to the radio, and the aching “She’s Leaving Home,” from my mother’s copy of the Beatles’ Love Songs double album. I’d never heard “Lovely Rita,” though, with those cascading harmonies in the refrain. And I’d certainly never heard “A Day in the Life,” nor was I prepared for it, for Lennon’s somber, almost disconnected voice in the first verses; for the orchestral crescendo coming out of those verses; or for how the band just drops you into McCartney’s workaday, up-and-at-’em scene, before the specter of Lennon floats you right back out of it. He’d love to turn you on, turn us all on, and turn me on, he did, right through that last crescendo, building and building and building, rummaging through increasing atonality and noise, all the way up to the final piano chord, that E-major that hammers down and then flutters out into the ether, cycling on forever.

And while, as I’ve said before, there’s nothing at all wrong with being able to point and click a link and hear just about anything you want these days, at any time, from any location, something just seems lost when the music is divorced from something tactile, something you can hold. In the case of Sgt. Pepper’s, for me, that something was that physical object—that album, that package, those sounds coming off that black wax. The CD couldn’t compensate, and my iPod—though portable and useful and damn near indispensable—sure as hell can’t, either.

And while, as I’ve said before, there’s nothing at all wrong with being able to point and click a link and hear just about anything you want these days, at any time, from any location, something just seems lost when the music is divorced from something tactile, something you can hold. In the case of Sgt. Pepper’s, for me, that something was that physical object—that album, that package, those sounds coming off that black wax. The CD couldn’t compensate, and my iPod—though portable and useful and damn near indispensable—sure as hell can’t, either.

I experienced the whole thing again recently, over the holidays, as I played a copy of the most recent Sgt. Pepper’s reissue—the 2009 remaster, on 180-gram vinyl, with the full complement of insert replicas and liner notes. The ritual of handling and playing the record, of looking through the rich visual material, of hearing those sounds again, with the new, clearer digital mastering—all of it was beyond satisfying. It reminded me of that first encounter, of engaging with the myth and mystery of the record, and finding out how closely the sounds I was hearing matched the ones in my head. In many ways, it was a revelation all over again.

Comments