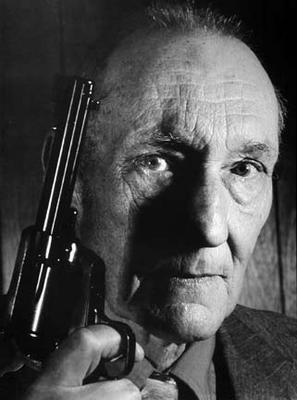

The works of William S. Burroughs are often lumped in with the Beat school; but although he was friendly with leading figures in the movement, his works were far more dark and paranoid than those of his compatriots. While Jack Kerouac tasted freedom in the blissed-out travelogue of On the Road, Burroughs brooded over the systems of control encoded into our very thoughts. Employing the imagery of pulp sci-fi, he characterized language itself as ”a virus from outer space,” an intangible invader engineered to keep human minds enslaved. His distrust of language led him to the ”cut-up” method, literally taking a scissors to his texts and reassembling them at random. Only by breaking the ingrained patterns of language, he argued, could we break the programmed patterns of our thoughts.

From his youth, Burroughs despised all institutions of control — which makes it rather surprising to find that he spent almost a decade enthralled by the Church of Scientology. During the 1960s, while living in England, Burroughs took many courses at the church’s UK headquarters, and wrote extensively in praise of Scientology and its founder, L. Ron Hubbard. Eventually disenchanted by its authoritarian strain, he became a bitter critic of the organization; but he never disavowed its methods, and kept one of the church’s infamous ”e-meter” devices on hand for personal use for the rest of his long life (Burroughs died in 1997).

Many critics play down this entanglement with Scientology; it doesn’t jibe with Burroughs’ image as a hard-boiled cynic. But for David S. Wills — scholar of the Beat movement, founder of the literary journal Beatdom, and author of the new biography Scientologist! William S. Burroughs and the ”Weird Cult” (Beatdom Books), the writer’s flirtation with the CoS stemmed from his famously tormented personal life, which included childhood sexual abuse, long-closeted homosexuality, self-injury, and the shooting of his second wife Joan at a drunken party. ”He just wanted something that would fix all the things inside him that hurt, or caused him pain or difficulty,” Wills says.

A native of Scotland, David Wills is an avid traveler. He has roamed across Europe and Asia, with a long-term residence in South Korea. I reached him by email at his current home base in Hefei, China.

Scientologist! focuses on such a singular aspect of Burroughs’s life and work — it sounds like a subject for a scholarly monograph, of interest to devotees only. But in practice, the book works wonderfully as a general overview biography; well-researched, hitting on all the high points, giving the full shape of the man and his career. Was it your intent to keep the book accessible to readers who might not have known much about either Burroughs or the Church of Scientology?

I really wanted to make it accessible because I knew that a lot of the readers would probably be familiar with one topic or the other, but not both. Besides, I felt that to really do the subject justice I would need to show Burroughs’ entire life — from childhood traumas right through to his death. If I jumped straight into the use of Scientologese within his more difficult texts [the cut-up novels Nova Express and The Ticket That Exploded], I think a lot of readers would be really put off.

The portrait of Burroughs that emerges is fair, even sympathetic — but it’s not particularly flattering. Is it tough to maintain that balance? I imagine that when you’re dealing with writers whose work you admire, there’s an impulse to want to protect their reputations…

Yes, I absolutely agree with you. I think one apprehension I had towards the end of this project was knowing that most of the readers are going huge Burroughs fans. I tried to be as accurate as possible but I was certainly worried that there would be a bit of disappointment among these people. I know that particularly among fans of Jack Kerouac there is a tendency to judge these sorts of books and article and essays based upon how sympathetic the perspective of the author is. But in my view an author’s work needs to be approached seriously and without bias. My goal was just to put down on paper what the research turned up, which was that Scientology was a pretty huge obsession for him.

People always ask me, ”How can you like Burroughs?” or ”Do you actually enjoy those books?” and I always reply, ”He’s fascinating.” It’s not a matter of liking or enjoying for me. So I don’t feel the same sort of attachment to the subject, and therefore never really worried about protecting his reputation.

A larger point about the Beats: there was some quality work there, but also, frankly, some pretty sketchy personality types. Do you think that’s why the Beat movement has been relatively little-studied? Do the personalities, the baggage, make it difficult to approach the work in itself?

There is definitely something to that. I think that there is a perception, also, of the Beats as somewhat juvenile, which is probably tied in to the criminality you mentioned, but also related to the angst and sentiment that was so prevalent in their work. I think Burroughs, in particular, gets little attention because of his interest in things like Scientology and magic. These clearly detract from his credibility, and I think few scholars want to get involved in analyzing this bizarre mix of pseudosciences and the occult. It’s hardly surprising, then, that his biographers were both friends of his, and that a lot of the commentary on his work comes from people already interested in, say, magic.

There is definitely something to that. I think that there is a perception, also, of the Beats as somewhat juvenile, which is probably tied in to the criminality you mentioned, but also related to the angst and sentiment that was so prevalent in their work. I think Burroughs, in particular, gets little attention because of his interest in things like Scientology and magic. These clearly detract from his credibility, and I think few scholars want to get involved in analyzing this bizarre mix of pseudosciences and the occult. It’s hardly surprising, then, that his biographers were both friends of his, and that a lot of the commentary on his work comes from people already interested in, say, magic.

It’s apparent that you’re making an effort to be fair to the Church of Scientology as well — sticking to the public record insofar as one exists, with very little editorializing on your part. Was that primarily a stylistic decision, or (given that the Church is notoriously litigious) a legal one?

In the beginning it was definitely a factor, albeit a small one. From the start I never wanted to attack the Church — it’s an easy target, and the evidence is there for all to see, regardless of what I say. But I just wanted to explore the interest it held for Burroughs. As time went on, it became clear (no pun intended) that there really wouldn’t be anything that controversial — at least from their point of view. I was never able to get any sort of comment from the Church regarding Burroughs, but quite a few Scientologists and ex-Scientologists were willing to speak with me. They didn’t appear to view the project as likely to stir up any trouble.

The characterization of Burroughs as impressionable, even gullible, is unsettling — because it clashes so badly with the author’s public persona; hard-nosed, unsentimental, skeptical. How do you square the two? How does the wide-eyed naÁ¯f present himself so convincingly as the hard-boiled cynic?

Yes, this is something that I was a little surprised about myself. The more I dug into his files, the more it became apparent that this was a badly scarred man in search of a cure. I think he did present the image of himself as a strong and skeptical man, but once you get into his letters and articles from the sixties you really start to see the layers peel back.

It makes sense that his various traumas would lead him to dabble in psychoanalysis and drugs. But throughout his life he was also drawn to all manner of dodgy occult techniques.

I think it’s down to his perception of himself. He always thought of himself as a skeptic and renegade thinker. He did, as you say, distrust authority, and as is particularly evident from his time in Texas, he believed in the freedom of the individual from government and police, et cetera. So naturally he gravitated towards what he considered to be the suppressed technologies and ideas. The trouble was, everything eventually turned out to have a system of control behind it, and he was always hashing together his own version of these findings.

Because he would never submit himself fully to any guru or course of study. But he wasn’t really a systematic thinker, and he would discard one set of teachings and move on to the next obsession.

I wouldn’t say that he’d fall for any old trick… but he did fall for some pretty bad stuff. In the end, though, you have to realize that he was always looking for that cure. He just wanted something that would fix all the things inside him that hurt or caused him pain or difficulty. And Scientology promised everything he could hope for, and it seemed that it actually worked for a short while.

I’m not sure how exactly he managed to pass himself off as a cynic… but I suspect it’s because he was so cynical about the government and other popular targets. He was also a brilliant speaker and writer, and when he chose to take something apart, he was really convincing. Some of his anti-Scientology writing is excellent, and became better-known than his pro-Scientology stuff.

In the video below, the unmistakable voice of William S. Burroughs explains who’s really in control:

There’s a large and colorful ”supporting cast” around Burroughs throughout his life, and it’s fun to finally learn something about some of these lesser-known characters in that circle. Brion Gysin, for instance — Burroughs talked about him a lot, but as far as actual biographical information, he was a rather shadowy figure. Did you have a favorite ”secondary character” — someone who really stood out in your research, who made an unexpected impression on you?

Burroughs had a surprisingly long life, and so there were a huge number of faces moving in and out. I always liked Kells Elvins — the childhood friend who repeatedly pushed Burroughs into writing. He seemed like a colorful character, and definitely one whose influence is not well-known, unlike Gysin’s. Some of the people at the Beat Hotel are really great to read about, too, and the background characters that he references from his time in Mexico City and Tangier.

One character that I’d like to have learned more about was John McMaster — the spokesperson for the Church of Scientology, who later defected and became a friend of Burroughs. After he left the Church, there wasn’t a great deal of information available about him, but his name kept popping up from people who’d visited Burroughs, and always the same claims about him being the first ”clear.”

Although Scientologist! deals primarily with events of the 1960s, it feels contemporary. The hacking group Anonymous and high-profile defectors like Paul Haggis have put the Church of Scientology back into the spotlight; P.T. Anderson’s film The Master found inspiration for its fiction in the life on L. Ron Hubbard; and of course December 2012 brought the end of the Mayan Long Count calendar that so obsessed Burroughs. So why now? What is there in the zeitgeist that’s making all this stuff bubble up again?

Your question is particularly interesting given the actual size of the Church. It really doesn’t have many members, and seems to be shrinking by the year. By all rights it should be just another silly cult that few people pay any attention to, but it’s not. I think Hubbard’s plan for celebrity members is really paying off as we become increasingly obsessed with fame and as technology makes it easier for these pay to have an influence. What you have is an increase in evidence against the Church, which is unlikely to have much of an effect on the current members. Indeed, the criticisms help to some degree by publicizing the organization.

I really enjoyed The Master. Before watching it I somehow was told that it’s not really about Hubbard and Scientology, but instead just a vaguely similar story that is given attention because Hoffman looks like Hubbard… But then I watched it, and the language is unmistakable. The writer clearly included elements that could have come from nowhere else. I actually sat making these comments to my wife during the movie, and totally ruined it for her.

Next year, 2014, will be Burroughs’ centenary year. Any special plans for yourself, or for Beatdom Books?

The Burroughs and Beat communities do enjoy a good anniversary. We recently had ones for the publication of Naked Lunch, On the Road, and Howl. I’m glad that people keep these texts in mind and that their lessons are not forgotten. These books are timeless — Burroughs more so, as his books deliberately ignored the notion of time. Their lessons are important, and the lessons that came with their triumph over the censors, too.

Personally? I have always wanted to see Tangier. That would be a good way to mark the anniversary.

Many thanks to David Wills for his patience and graciousness. Scientologist! William S. Burroughs and the ”Weird Cult” is available on Amazon. (Read it, it’s good!) You can also find David on Twitter @beatdom.

Comments