Writing fiction is both art and science, but never does it feel more like a science than when the fiction is very short. The traditional elements of story — dialogue, action, character development, description — all take time, and words. Sometimes, to keep a short story from turning long, something has to give. Writing a very short story can feel like balancing an equation; one or more of those traditional elements of fiction may have to be omitted entirely, or the variable substituted with the X of clichÁ©, leaving the work feeling incomplete or undercooked.

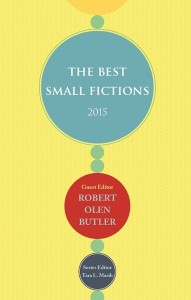

It’s an unforgiving form, is what I’m saying, so tricky to do well that you wonder why anybody even tries. Yet writers of great talent still do, and 55 of them are represented in The Best Small Fictions 2015, due in October from Queen’s Ferry Press — the inaugural volume in a new series, the first annual compendium to be devoted to the form since the 1952—1960 run of Robert Oberfirst’s Anthology of Best Short-Short Stories.

It’s an unforgiving form, is what I’m saying, so tricky to do well that you wonder why anybody even tries. Yet writers of great talent still do, and 55 of them are represented in The Best Small Fictions 2015, due in October from Queen’s Ferry Press — the inaugural volume in a new series, the first annual compendium to be devoted to the form since the 1952—1960 run of Robert Oberfirst’s Anthology of Best Short-Short Stories.

But if the perils of the short-short are apparent in this line-up (curated by guest editor Robert Olen Butler, with Stuart Dybek already on deck for the next edition), it nonetheless emerges as perhaps the most effective form for providing a window into the life of someone unlike oneself — precisely because of what the stories leave out.

Cartoonist and theorist Scott McCloud, in his seminal Understanding Comics, posits that abstraction facilitates identification. To wit: While a photographic likeness can by its very nature represent only a single individual, a cartoon face, abstracted to a circle, two dots, and a line for a mouth, becomes an icon standing for the idea of a face, any face — even the viewer’s own. It works the same way in prose fiction. Without an extensive backstory to act as a barrier to entry, we can more easily imagine ourselves in the protagonist’s place.

The best of these stories drop us, with a minimum of hand-holding, into moments of human extremity. Here we find vignettes of medical calamity, such as George Choundas’ ”You Will Excuse Me,” wherein a private act brings an awful realization, and Randall Brown’s ”Lithopedion,” which finds a woman delivering a miscarried infant of stone twenty years after the end of her marriage.

In these small fictions — a term that here encompasses flash fictions, haibun, 100-word exercises, Twitter fictions, iStories, and other variants — we find both the aftermath of disruptive violence, as with Emma Bolden’s ”Before She Was a Memory,” and the awful immediacy of the thing itself, as in Julia Strayer’s ”Let’s Say.” We find, too, wry observations of cultural dislocation, as with Yennie Cheung’s ”Something Overheard,” which takes off when the narrator eavesdrops on the weeping of a glamorous immigrant neighbor.

In David Mellerick Lynch’s ”The Lunar Deep,” we feel the sting of mortality in the loss of a loved one to dementia, while a host of minimalist tragedies — privation, messed-up families, bad relationships, societal pressures warping the timber of humanity — are made vivid in standouts like Casandra Lopez’s ”Mama Says,” Lauren Becker’s ”Annabel,” Zack Bean’s ”Bad Boys,” Lindsey Drager’s ”Reasons for Elevators,” and Danielle McLaughlin’s ”Shaping Air.”

Not everything here works equally well, of course. Trying to balance brevity with impact, some writers opt for shock, confusing grotesquerie with insight. And the quality of the prose is, inevitably, variable — a particular problem in such a hyper-compressed format, where each word, each phrase, takes on a disproportionate importance. Some stories are sunk by small missteps that might pass in a longer work: a single image poorly chosen, or one line of dialogue that drops with a clang.

But an excess of caution can be poisonous, as well, and a number of stories fall prey to a peculiar stylistic sameness, leading to (relatively) long stretches of self-consciously immaculate prose, all fraught and mannered and delicate, with any trace of swagger or joy workshopped right out of it; exquisite but lifeless.

The selection has some of that same homogeneity. This year’s edition of Best Small Fictions is top-heavy with high-minded ”this is how we live now” stories, and virtually no genre fiction. In playing to the strengths of the short-short as an invitation to empathy, this makes a certain sense. But it does not compromise the form’s respectability to acknowledge the uses to which it has been turned in the past, and given small fiction’s proud history in the SF, mystery, and horror traditions, it nonetheless seems a curious omission. After all, in its 1950s heyday Oberfirst’s Anthology regularly showcased the likes of Ray Bradbury, Henry Slesar, and John D. MacDonald. We can only hope this issue will be addressed — or at least justified — in future volumes.

Even so, it’s not all poker faces and kitchen sinks. There’s room in Butler’s taste for the outright absurdity of Dan Moreau’s ”Dead Gary” — a gentle workplace comedy, its titular zombie notwithstanding, with a bittersweet emotional punch — and Chris L. Terry’s ”At Home With Rapper’s Delight,” which anthropomorphizes the beloved hip-hop classic as an aimless twentysomething puttering around the house with his buddy, The Message, and pondering his legacy.

And for all the limitations of small fiction, both inherent and editorially imposed, there are still wonders to be found. Perhaps the best of these fictions, Misty Shipman Ellingburg’s ”Chicken Dance,” delivers both a masterfully devastating account of an awkward college mixer and a meditation on the limits of ethnic solidarity, all in 100 words. Within the rigors of that limit, Shipman finds room for a lovely sentence: ”My, my.” Two valuable words, seemingly thrown away. But in context, they act as a pause, a punchline, a flourish, a signifier of both growing attraction and subtle mockery. It’s a tiny marvel nested inside a marvel, and — as with the volume as a whole — the deeper you go, the more there is to see.

This review was commissioned by the editors of KYSO Flash, and appears here by permission.

Comments