Bitch Planet makes no bones about being a dangerous object. The bold, garish cover art seems made to be viewed under a black light. The color registration is purposely off, for an artful shoddiness recalling the look of a low-budget samizdat tract. But peer beyond the lurid exteriors of Bitch Planet — the first five issues of which are collected in the new trade paperback Extraordinary Machine — and you’ll find in its back pages footnotes on intersectional feminism, and a discussion guide for book clubs. Plainly, there’s more going on here than cheap thrills.

Bitch Planet makes no bones about being a dangerous object. The bold, garish cover art seems made to be viewed under a black light. The color registration is purposely off, for an artful shoddiness recalling the look of a low-budget samizdat tract. But peer beyond the lurid exteriors of Bitch Planet — the first five issues of which are collected in the new trade paperback Extraordinary Machine — and you’ll find in its back pages footnotes on intersectional feminism, and a discussion guide for book clubs. Plainly, there’s more going on here than cheap thrills.

But it is a thrilling work. Co-created by writer Kelly Sue DeConnick and artist Valentine De Landro, Bitch Planet is a righteous, riotous hoot, a pitch-black spoof with a deathly serious feminist theme. For DeConnick, it’s a career best — the breakthrough that will propel her from cult figure to superstar. It’s the very definition of a passion project: audacious, subversive, fairly glowing with love and anger. And it’s the most exhilarating comic I’ve read in years.

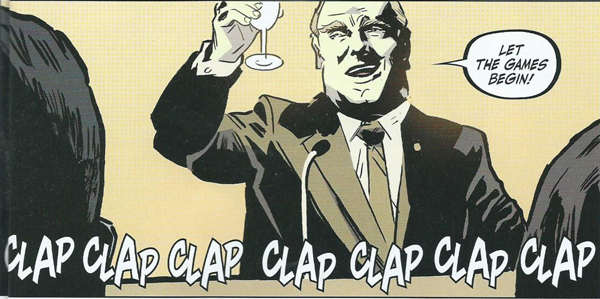

The action of Bitch Planet is set in a satirical dystopia wherein the institutional sexism, racism, and fundamentalist mania of American society are not implicit underpinnings but foundational principles. A near-future planet Earth is governed by the Protectorate, a patriarchy that combines the worst elements of Christian Dominionism and corporate oligarchy. Under the rule of the Council of Fathers, women’s lives are rigidly proscribed, and all citizens are indoctrinated in retrograde sex roles both by the education system and the ubiquitous media. Men can be pacified with bread and circuses; but for women who cannot or will not negotiate a place in this society, the only option is exile.

Those who are branded ”non-compliant” — those women who refuse to be dumb and pretty, who will not accept being the property of a father or husband, women who insist on maintaining agency, women who are too sexually independent, too stubborn, too fat, too Black, or too queer — are shipped to the Auxiliary Compliance Outpost, a.k.a. ”Bitch Planet,” an offworld penal colony.

The protagonist, Kamau Kogo, is a former professional athlete who has taken voluntary exile for reasons of her own. Shortly after her arrival at the outpost, she is framed for the murder of another inmate. Prison officials approach Kamau with a deal. In exchange for clemency, Kamau must organize and coach a team of inmates to compete in Duemila, an annual gladiatorial-style sporting event. Duemila is televised worldwide, uniting the population and serving as a substitute for war. But ratings have been slipping in recent years. In hopes of rekindling interest in the event, the producers have decided to cast it as a literal battle of the sexes. Seeing Duemila as a chance for both escape and revenge, Kamau accepts the challenge.

There are multiple influences at play in Bitch Planet — both highbrow and lowbrow. The book’s guiding spirits are Margaret Atwood on the one hand and Pam Grier on the other. Aside from The Handmaid’s Tale, there are multiple reference points in junky pop culture: The Hunger Games, The Longest Yard, Rollerball, Death Race, Foxy Brown, The Big Birdcage. Writer DeConnick is playing a very smart game here, using the trappings of exploitation cinema — stoic heroine, splashy violence, plentiful nudity, an adversary as comical as it is sinister — to sound an indignant howl against repressive systems that seek to marginalize or silence women’s voices. She holds the clichÁ©s of these fantasies up to the light to reveal the grimy male fingerprints all over them. The ”obligatory shower scenes” lay bare the implicit degradation of the trope. Three inmates act out a steamy sex scene as a distraction for a guard who they know is spying on them, literalizing the male gaze; DeConnick knows what boys like, and she’ll shove it down their throats til they choke.

Valentine De Landro is an ideal collaborator in this. His stark, expressionistic shadows and rough-hewn figures are reminiscent of Croatian master Danijel Žeželj, but with a pop-art sensibility that suits Bitch Planet down to the ground. De Landro draws the kind of women’s bodies you don’t often see in comics, setting them in a landscape of blaring video screens. He particularly nails the way that patriarchal propaganda aims simultaneously for titillation and disgust, promoting women as objects of desire even as it fosters contempt for their personhood. It’s disturbing, but always with a cartoony edge that saves it from grimness. Robert Wilson IV provides art for chapter 3, his slick lines in marked contrast with De Landro’s; the soft brushwork creates a sort of nightmare Archie look, as we follow big, bold breakout character Penny Rolle on her journey from innocent girl to unapologetic bruiser within a system designed to crush the spirit out of her.

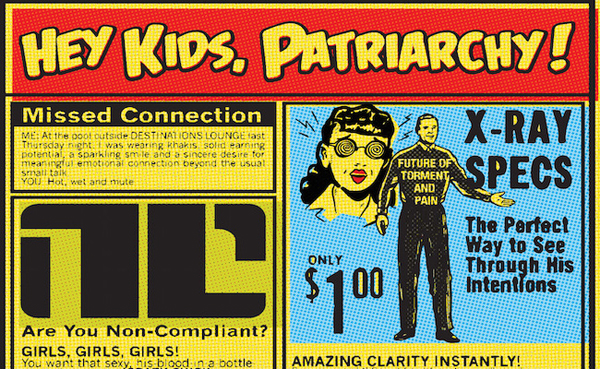

Every comic is a collaborative effort, and Bitch Planet’s entire creative team is on board with the overall effect. State-of-the-art design and coloring strategies give it the look of an escapee from the quarter bin of some particularly disreputable comics shop. Colorist Cris Peter uses the digital palette of modern comics only sparingly, hewing largely to a flatter scheme that pops against De Landro’s masses of black. Designer Rian Hughes masterfully captures the trashy retro aesthetic, with covers evoking exploitation film posters, smudgy faux-advertisement pages (laid out by Laurenn McCubbin) recalling those found in comics of the 1970s, and endpapers swarming with gaudy benday dots. Bitch Planet’s pages even simulate the ivory dinge of yellowing newsprint.

But Bitch Planet is the writer’s show, first and foremost. Kelly Sue DeConnick is a writer with a passionate fan base, and I’ve always admired her ambition and her unsparing politics, even if I have occasionally been frustrated with the execution of her work. On Bitch Planet, though, she is burning. DeConnick’s mastery of form and storytelling is on display from the first issue, with a long and intricate montage that cross-cuts between the emotional breakdown of a new prisoner and the desperate machinations of the husband who sent her away. It’s a bravura sequence, loaded with switchbacks and head fakes, and it lands like a gut-punch. It’s rousing, terrifying, heartbreaking, and bitterly comical, all at once.

But Bitch Planet is the writer’s show, first and foremost. Kelly Sue DeConnick is a writer with a passionate fan base, and I’ve always admired her ambition and her unsparing politics, even if I have occasionally been frustrated with the execution of her work. On Bitch Planet, though, she is burning. DeConnick’s mastery of form and storytelling is on display from the first issue, with a long and intricate montage that cross-cuts between the emotional breakdown of a new prisoner and the desperate machinations of the husband who sent her away. It’s a bravura sequence, loaded with switchbacks and head fakes, and it lands like a gut-punch. It’s rousing, terrifying, heartbreaking, and bitterly comical, all at once.

If there is a false note in this volume — and right now it’s more like a question mark — it is that he women of the Auxiliary Compliance Outpost, from the moment they arrive, all seem united against the patriarchal bastards who run their world. This seems out of line both with the clichÁ©s of prison films, where inmates are more in danger from each other than from the guards, and with the principle of divide-and-conquer that authoritarian regimes employ in the real world — tacitly encouraging factionalization among the resistance, co-opting dissent to make marginalized groups complicit in their own oppression. (Not to mention the way that real-world patriarchy encourages women to police each other’s bodies and lifestyle choices; just watch the fireworks if, for instance, a public figure announces that she doesn’t want to have kids.) If there are rival gangs on the Bitch Planet, we have yet to see them.

It’s early days, though; and a few well-placed hints in Extraordinary Machine tease that Bitch Planet will be going in some fascinating directions in the future. It’s a series to watch — but be mindful of that gaze, because Bitch Planet is watching you right back.

Comments