On December 13, 1975, Saturday Night Live, then in its first season, aired a short film by Albert Brooks in which the actor-comedian addresses the show’s audience from bed. “I’m sick this week,” he says, and to prove it he puts his doctor, played by future SNL writer-performer Harry Shearer, on speakerphone to explain that Brooks is “overworked.”

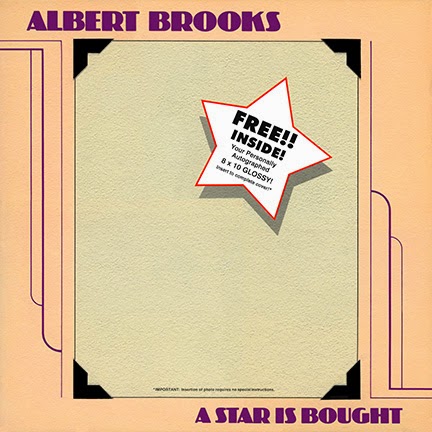

A few minutes later a delivery boy arrives with an order of broasted chicken and tells Brooks how much he likes his new comedy album, A Star Is Bought.

“Why don’t more people know about it?” the delivery boy asks.

“Why don’t more people know about it?” the delivery boy asks.

“I don’t know,” says Brooks. “I just don’t know.”

“Why doesn’t your record company take out ads?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know.”

“I mean, what do they do, spend all their money promoting the Eagles?”

Since David Geffen’s film company later bankrolled two of Brooks’s best movies, Lost in America (1985) and Defending Your Life (1991), I assume Brooks was merely teasing Asylum Records, the label Geffen cofounded in 1971, for the tepid sales of his second album — as far as I can tell, it failed to crack the Billboard 200, then known as the trade publication’s Top LPs & Tape chart — but the fact is he never made another. And after one more short film for Saturday Night Live — Brooks’s rising star, thanks to numerous appearances on The Tonight Show, had helped NBC convince its affiliates of SNL‘s worth prior to the series’s debut, but by January of ’76 Lorne Michaels and the Not Ready for Prime Time Players were well on their way to establishing their own comic identity — he began to focus on film acting (Taxi Driver, Private Benjamin) and writing, directing, and starring in his own feature-length comedies, eventually earning him the nickname “the West Coast Woody Allen,” though he could just as easily have been labeled “the Todd Rundgren of comedy,” a wizard and true star of his chosen field who wasn’t interested in staying in one creative place for too long.

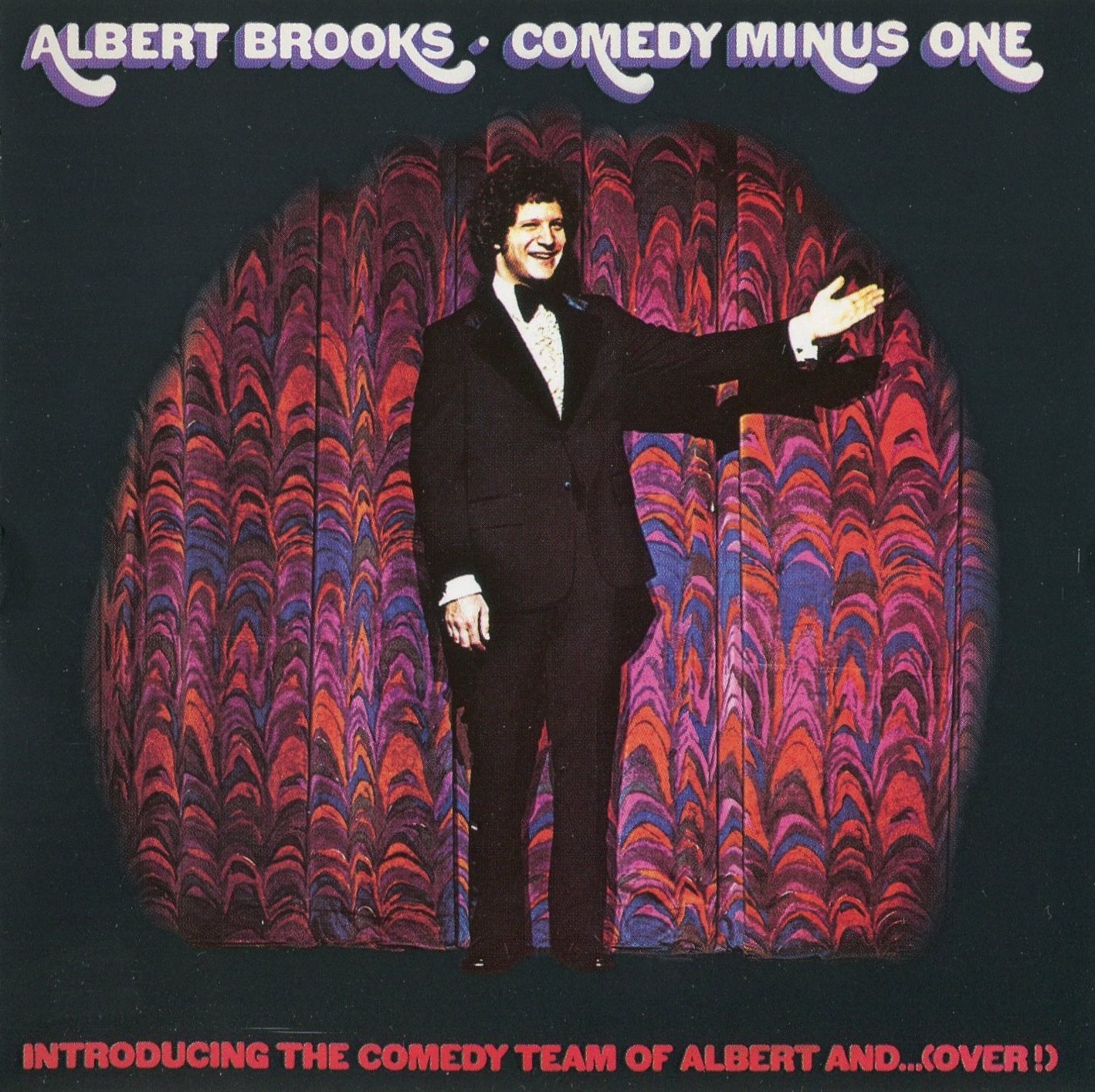

Allen made three comedy albums of his own between 1964 and ’68, but, with all due respect, they don’t hold a candle to A Star Is Bought or Brooks’s first LP, Comedy Minus One, released in 1973, on ABC Records, a few months after Brooks turned 26.

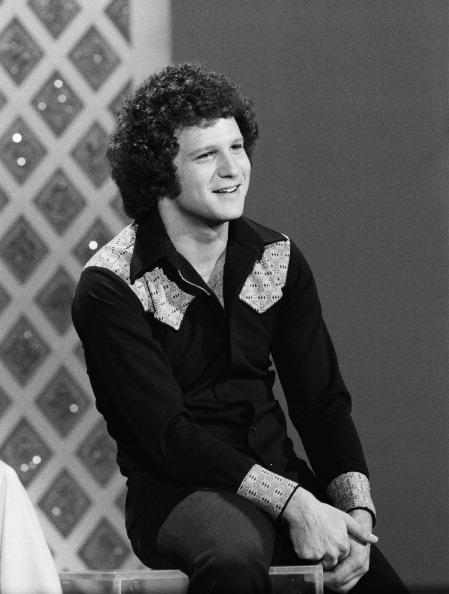

Albert Brooks on the set of The Helen Reddy Show, summer 1973 (photo credit: Herb Ball/NBC/NBCUniversal Photobank via Getty Images)

Comedy albums don’t always stand the test of time, and the same goes for stand-up comedy. If you came of age in the ’60s Lenny Bruce’s acid wit may have been revelatory, but when I first heard his routines in the HBO documentary Lenny Bruce: Swear to Tell the Truth (1998) I struggled to connect. The same was true of Richard Pryor’s material in his stand-up film Live in Concert (1979) and Steve Martin’s jokes on his album Comedy Is Not Pretty! (1979) — and I think Martin’s one of the all-time greats of American humor.

I sometimes wonder if my nieces would similarly scratch their heads if, in a decade or so, I were to share with them the Bill Hicks, Chris Rock, and Patton Oswalt albums that I began listening to, repeatedly, in my 20s. Maybe I’ll be scratching my own head. “Humor tends to evaporate with time, and what is interesting in 1925 will probably be less so almost half a century later,” wrote Ian Frazier in The New Yorker last February, referencing issues of the magazine from its earliest years that he’d read cover to cover for a college thesis.

Frazier’s a funny guy, so he should know. Funny is fluid. (Fluids, on the other hand, can be funny, just as long as the other hand isn’t yours.) But when comedy is built on a foundation of ideas and concepts rather than one-liners, it may be better equipped to fight the long-term effects of generational audience erosion.

Luckily, I didn’t hear Albert Brooks’s two comedy albums when they were new, so I won’t say, “You had to be there.” You didn’t. And, four decades later, you still don’t.

“My audience has lots of people between 20 and 35, but there are always a few 60-year-olds, and it makes me happier than if everyone was 22,” Brooks told Rolling Stone reporter Judith Sims in January 1974. Because he never played to one age group, his comedy became ageless.

I bought Comedy Minus One in college, on CD, back in 1996, and immediately liked how Brooks used standard comedy-album elements such as stand-up routines and short sketches to comment on the format. After a brief introduction in which he explains, “When you hear the yodel you turn the record over,” the listener is taken to the Troubadour nightclub in West Hollywood, where Brooks informs his audience that an album is being recorded. He gently reminds them, “Don’t identify your laughter,” and demonstrates by laughing heartily, then adding, “Said Bill Harrison of Phoenix!”

Brooks proceeds to tell the Troubadour crowd about his experience as an opening act for Neil Diamond and, most memorably, Richie Havens, whose toked-out but amped-up fans had no interest in listening to an opener, especially a stand-up comic. Brooks had hoped that a local radio DJ would be at the venue to introduce him because “he would come out and the audience would get some of their hostility off on him,” he says. “Audiences hate disc jockeys, and they have a right to because, generally, for the most part, disc jockeys are the worst human beings in the world. Now, look, if there are some disc jockeys here tonight, you might be different. A disc jockey playing this record right now might be a great guy or gal.”

Brooks proceeds to tell the Troubadour crowd about his experience as an opening act for Neil Diamond and, most memorably, Richie Havens, whose toked-out but amped-up fans had no interest in listening to an opener, especially a stand-up comic. Brooks had hoped that a local radio DJ would be at the venue to introduce him because “he would come out and the audience would get some of their hostility off on him,” he says. “Audiences hate disc jockeys, and they have a right to because, generally, for the most part, disc jockeys are the worst human beings in the world. Now, look, if there are some disc jockeys here tonight, you might be different. A disc jockey playing this record right now might be a great guy or gal.”

“Brooks is not like [George] Carlin, [Robert] Klein or Pryor (and certainly not like Cheech and Chong), who bring humor to fairly ordinary situations (though Brooks does that too),” wrote Judith Sims. “Brooks’ strength is in the unexpected twist of an already bent imagination.”

Five years later, in a profile for The Village Voice, Paul Slansky wrote, “Aside from Albert’s comic instinct, the most striking thing about him is his confidence in it. His jokes are delivered as casually as they occur to him. It’s clear that if he thinks something is funny, he goes with it — getting a laugh is a pleasant but nonessential bonus,” an observation Brooks himself echoed in a 2006 A.V. Club interview with Scott Tobias: “I think that comedy can and should be done as many times as the comedian wants to do it, and I don’t even know that laughter should be the main consideration. It should be how it feels coming out of him, if he feels it’s a good bit … To me, the whole point of comedy is to just go fucking crazy and try things that are as wild as your brain can think of — and do ’em again if they don’t work. Do ’em again! Believe me, the audience comes to you.”

Halfway through his “Memoirs of an Opening Act” routine, and only six minutes into Comedy Minus One, Brooks dissolves to “a department store in the midwest” to ask a listener what she thinks of the record “so far.” I won’t ruin the joke, but it contributes to the overall “meta” brilliance of Comedy Minus One, a quality that’s reinforced when the end-of-side-one yodel Brooks mentioned in the introduction arrives ahead of schedule, when side two begins with a demonstration of stereo sound via a ping-pong match that turns into a car accident — it’s basically a joke about Asians being bad drivers, a stereotype that a non-Asian comedian, especially one as intelligent as Brooks, presumably wouldn’t attempt today without a reversal that makes the comedian the butt of the joke — and when he ends the album with the 12-minute title track, an old-fashioned routine called “The Auto Mechanic” for which the script is provided inside the CD’s booklet or the LP’s gatefold. It’s up to the listener to read the dialogue assigned to “You” and not step on Brooks’s lines or the prerecorded laugh track; as Brooks says before the routine begins, “You will have to practice until you can feel just how much of the laugh to let die down before you continue. This is called timing. Say it with me — timing.”

The January 2013 issue of Vanity Fair, guest-edited by Judd Apatow, features a Q&A with Brooks, who Apatow directed in the movie This Is 40 (2012). (The interview is reprinted in Apatow’s book Sick in the Head: Conversations About Life and Comedy, published last June.) When asked about comedic influences, Brooks mentions Jack Benny and says they had both been guests on an episode of The Tonight Show early in Brooks’s career. Benny enjoyed the younger comedian’s routine, in which Brooks pretended to be a European elephant trainer whose pupil had gone missing en route to America, forcing him to use a frog instead. At the end of the show, when Johnny Carson asked Benny where he’d be performing next, a prompt Benny had requested during a commercial break, he answered, according to Brooks, “Never mind about me — this is the funniest kid I’ve ever seen!” Brooks describes the moment to Apatow as “this profound thing. Like, Oh, that’s how you lead your life. Be generous and you can be the best person who ever lived.”

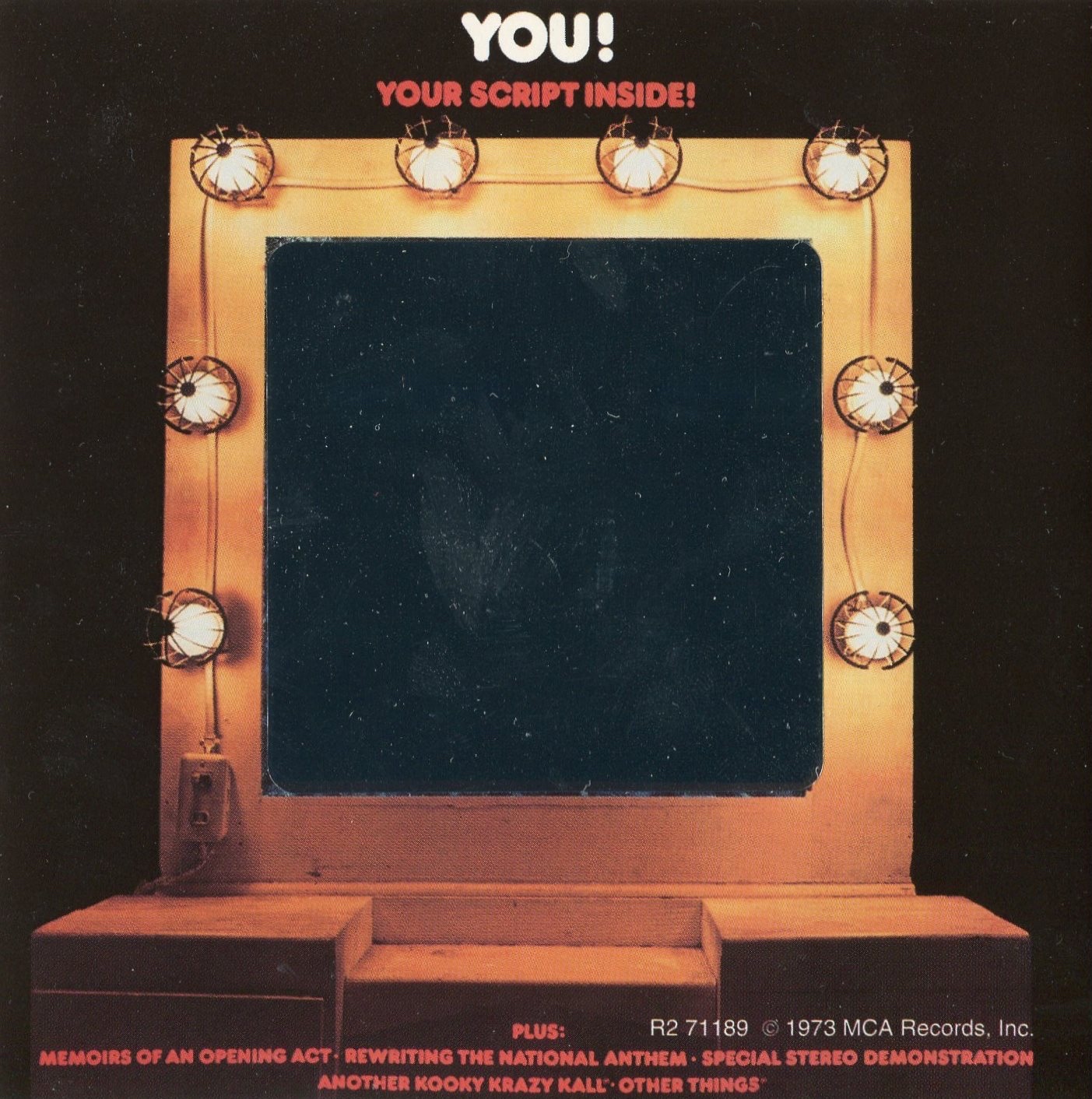

That sense of generosity can be felt on Comedy Minus One; the back cover even provides a plastic mirror to show off Brooks’s new comedy partner: “You!” The first time I performed “The Auto Mechanic,” lying on the floor in front of my boombox, I almost felt like a child again, giddily reciting a punch line to get a laugh — Brooks plays the straight man, also a generous move — even though I knew full well the laugh would be there regardless of whether or not I delivered my lines. The act of performing is at the center of Comedy Minus One, from Brooks’s stories about opening for rock stars to the yodeler blanking on his cue or the woman in the department store telling Brooks what she thinks he wants to hear about the album’s sales prospects. And these days almost everybody’s a performer on social media, where an audience is always available to like, heart, or retweet us as long as we keep generating material, no matter how banal. It’s why Comedy Minus One still adds up more than 40 years later.

That sense of generosity can be felt on Comedy Minus One; the back cover even provides a plastic mirror to show off Brooks’s new comedy partner: “You!” The first time I performed “The Auto Mechanic,” lying on the floor in front of my boombox, I almost felt like a child again, giddily reciting a punch line to get a laugh — Brooks plays the straight man, also a generous move — even though I knew full well the laugh would be there regardless of whether or not I delivered my lines. The act of performing is at the center of Comedy Minus One, from Brooks’s stories about opening for rock stars to the yodeler blanking on his cue or the woman in the department store telling Brooks what she thinks he wants to hear about the album’s sales prospects. And these days almost everybody’s a performer on social media, where an audience is always available to like, heart, or retweet us as long as we keep generating material, no matter how banal. It’s why Comedy Minus One still adds up more than 40 years later.

Brooks especially gets a kick out of performers who are blind to their ineptitude, but his comedy is never mean-spirited or cynical (although if you’re a disc jockey, you might disagree). Comedy Minus One contains two tracks titled “Another Kooky Krazy Kall®” (Harry Shearer briskly informs the listener that it’s “a copyrighted feature”), wherein Brooks makes painfully unimaginative prank calls, and the second of Brooks’s two stand-up routines from the Troubadour is “Rewriting the National Anthem,” an open audition for average American citizens to replace “The Star-Spangled Banner” with a new anthem since “nobody sings it on the way to work anymore,” as Brooks laments. He performed a slightly different version of it on NBC’s The Flip Wilson Show on December 5, 1972, along with a supremely silly routine about a ventriloquist who doesn’t know the first thing about ventriloquism, but I think the bit works best without any visual accompaniment — Brooks is voicing a variety of characters, and part of the fun comes from picturing earnest patriots like Hal Carter and Robert “Bob” Harmon in the mind’s eye.

Another possible reason why Comedy Minus One hasn’t lost its luster is because Brooks is committed to producing an entirely aural experience. That may seem like a no-brainer, but on almost every stand-up album I’ve heard, there’s at least one moment in which the live audience reacts to something the comedian is doing that we, the listening audience, can’t see. That may be why Comedy Is Not Pretty! went over my head when I first heard it in 1998: Steve Martin’s success as a stand-up in the ’70s had a lot to do with his prowess as a physical comedian and his ability to deliver a joke through body language; without the visual element in play, his routines seem off-balance, like an audio tour of an art museum that doesn’t exist. Conversely, the late Bill Hicks’s stand-up is often more palatable to me on CD because I can’t see him pacing back and forth onstage, looking like he might pick a fight with the audience at any second.

I won’t argue that Brooks’s stand-up material on Comedy Minus One isn’t dated in some respects — Neil Diamond and Richie Havens are no longer two of the music industry’s biggest stars, after all — but the idea of Ford issuing a factory-recall roundup for its station wagons by holding a David Cassidy concert in Detroit still makes me laugh. (Replace Cassidy’s name with One Direction’s, and “station wagons” with “minivans,” and the joke is instantly updated.) It made the Troubadour’s audience laugh too, but that may not have been enough of a consolation for Brooks, who told Judd Apatow, “The irony is, if I didn’t bring a comedy album to a friend’s and sit down and listen to it with them, I never heard my comedy albums played. I’ve never heard reactions to them.”

Despite the patronizing prediction of that woman in the department store, Comedy Minus One wasn’t a hit. “When I released that record, I thought, Pity those poor salesmen; people are going to be trampling them to get their hands on that album,” Brooks said in another profile by Paul Slansky, this time for the July 1983 issue of Playboy. “That didn’t happen. The record wasn’t even in the stores.”

He could at least take comfort in knowing that it had been a big seller, for one night, in Los Angeles, thanks to the unconventional promotional efforts of John Lennon, who in 1973 was hanging out with Harry Nilsson, a friend of Brooks’s, during his separation from Yoko Ono. “I remember my album, Comedy Minus One, had just come out and was in Tower Records,” Brooks told Apatow. “So he and Harry and I went in. He bought them all. He bought three boxes of them. Then he drove down Sunset and hurled them out like Frisbees … He’s just throwing them out on the street. So it’s good and bad. I mean, it helped my Billboard number, but now they are all over Sunset.”

Albert Brooks (far left, against back wall) out on the town with Keith Moon (third from left), Ringo Starr (fourth from left), and John Lennon (seventh from left) in the early ’70s (photo credit: fuckyeahalbertbrooks.tumblr.com)

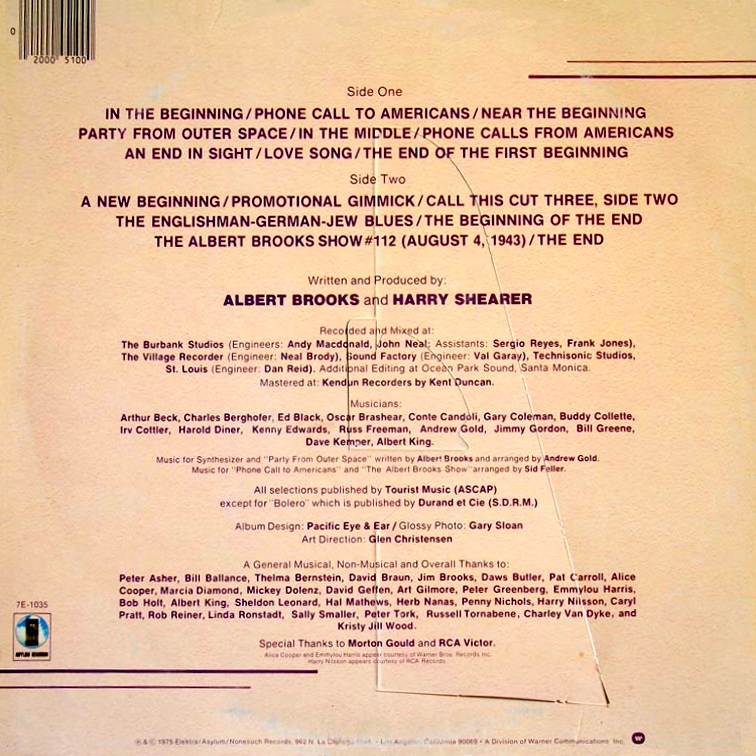

Nilsson sings a few bars on Brooks’s follow-up, A Star Is Bought, which is even less of a traditional comedy album than Comedy Minus One. (It received a Grammy nomination for Best Comedy Album in 1976 but lost to Richard Pryor’s … Is It Something I Said?, the second of three consecutive wins for Pryor in that category.) For starters, it doesn’t contain any stand-up material — Brooks abruptly retired from live performing while promoting Comedy Minus One — and the sketches are disguised as songs because … well, I’ll allow disc jockey Charlie Van Dyke, the album’s narrator, to explain: “In all the years that recording artists have been trying to get on the charts, those elusive indexes of what’s selling, nobody ever did what comedian Albert Brooks has done. He’s assembled an album completely composed of cuts individually designed for different kinds of radio stations. In the next hour we’ll not only find out how this record came to be made, we’ll actually hear it.”

Once again, Brooks is satirizing a performer’s need for acceptance, the need to know that he or she isn’t creating in a vacuum. The biggest benefit of selling out is finally having proof that someone’s buying what you’re selling.

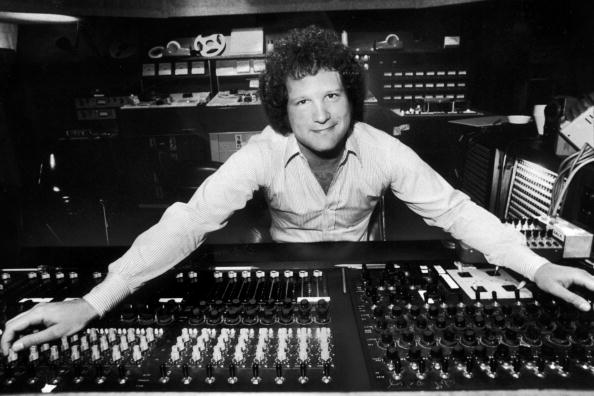

The attention to aural detail on A Star Is Bought goes even deeper than on Comedy Minus One. Brooks wrote and produced it with Harry Shearer (they had previously collaborated on “A Daddy’s Christmas,” Brooks’s 1974 holiday single for Asylum), who also counted Jack Benny as an influence, partly because he’d worked with the legendary comedian in the 1950s as a child actor on Benny’s radio and TV shows.

“He was a guy who dug the idea of other people on the show getting laughs, which sort of spoiled me for other people in comedy,” Shearer said in a 2003 interview with the A.V. Club‘s Nathan Rabin, adding, “I’d always loved radio. I loved Bob and Ray. I loved Stan Freberg. Then, when I started doing it with the Credibility Gap [a comedy troupe that also featured Michael McKean and David L. Lander before they were cast as Lenny and Squiggy on Laverne & Shirley], we did three 10-minute shows a day. You can’t do that on television. You can get an awful lot of effects into the customer’s mind for a great deal less time and money in radio than you can in television.” Shearer has hosted his own comedy show, Le Show, on public radio since 1983.

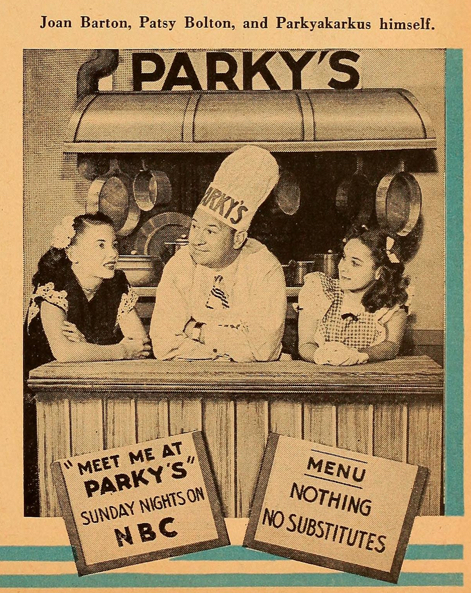

Brooks, though he was never a child actor, is the son of Harry Einstein, who played a Greek-immigrant character named Parkyakarkus in the ’30s and ’40s on Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor’s radio shows before headlining his own series, Meet Me at Parky’s. (Yes, Brooks’s real name is Albert Einstein. Comedy Minus One may not be as groundbreaking a theory as E = mc2, but Brooks is a genius in his own right.) Shearer and Brooks both grew up in the twilight of the Golden Age of Radio, surrounded by professional performers — entertainer George Jessel makes an appearance on Comedy Minus One‘s title track, a sign of Brooks’s respect for his father’s generation of comedians — and brimming with firsthand knowledge of the sitcom format that was quickly being co-opted by television.

Meet Me at Parky’s aired on the NBC radio network from 1945 to ’47, followed by a final season on the Mutual Broadcasting System. (image credit: oldshowbiz.tumblr.com)

The pièce de résistance of A Star Is Bought is “The Albert Brooks Show #112 (August 4, 1943),” a “lost episode” tailor-made for the nostalgia-radio format that was gaining traction in the ’70s. But it’s really an excuse for Brooks and Shearer to pay loving tribute to programs like Jack Benny’s, with Brooks playing the put-upon star of a variety-show-within-a-show. Its cast of characters includes Gladys, his sassy secretary, who writes her boss fan mail since “somebody has to do it” (sorry to ruin this particular joke, but she’s also his mother, and she’s played by Brooks’s actual mom, Thelma Bernstein, a singer and actress in the ’30s), and Edgar, his big galoot of a lawyer, who informs Brooks that he’s being sued by a man who claims he was slandered on last week’s show. “Last week’s show? What did I say?” Brooks asks. “You said he wrote it,” Edgar replies. (Sheldon Leonard, an actor on Meet Me at Parky’s as well as Benny’s radio show, among many others, pops up as Brooks’s producer, calling his star “Brillo-head.”)

Brooks told Judd Apatow that he loved Benny because of “his minimalism. And the way he got laughs. He was at the center of a storm, he let his players do the work, and just by being there made it funny. That was mind-boggling to me.” (I first saw Benny’s TV show in 2008, and my mind was boggled by how well his timing and delivery held up half a century later, an exception to Ian Frazier’s unofficial rule.)

Brooks and Shearer follow that template with “The Albert Brooks Show,” allowing the supporting players to get the biggest laughs, such as a World War II-era Japanese stereotype named Sam, who, similar to Rochester, the black valet played by Ernie Anderson on Benny’s show, is nobody’s fool. Unlike Anderson, however, who was black, the actor voicing Sam sounds like he’s neither Japanese nor Japanese-American but is familiar with Mel Blanc’s version of a native accent in Looney Tunes shorts produced after December 7, 1941. Brooks and Shearer seem to be referencing the fact that one of the Golden Age of Radio’s most popular shows, Amos ‘n’ Andy, starred two white actors, Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, as black southern stereotypes — or the fact that Brooks’s dad, a Russian-Austrian Jew from Boston, became famous as a broken-English-speaking Greek. More political incorrectness arrives in the form of Henry, a stuttering performer (voiced by Daws Butler, I believe, a.k.a. Yogi Bear, Huckleberry Hound, and Snagglepuss) whose speech impediment frustrates Brooks, much to the studio audience’s delight.

Albert Brooks in a Los Angeles recording studio, summer 1975 (photo credit: Julian Wasser/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

“The Albert Brooks Show” also makes time for a Series E War Bonds ad wedged into its star’s dialogue. There’s no joke in the ad itself, but this is comedy at a molecular level, brought to you in part by a guy named Albert Einstein, in which every atom of verisimilitude matters. “The thing that amazed me when I got to know him was his commitment,” Shearer said in Paul Slansky’s Playboy article. “Once he decides he’s gonna do something — whether it’s a movie or a joke — he commits to it totally, which frees him to go as far as he can. Even if it’s an idea that just occurred to him that minute, he’ll push it as far as possible.”

Another highlight of A Star Is Bought along those meticulously drawn lines is “Phone Calls From Americans,” a bid for heavy talk-radio rotation for which Brooks “not only took the calls,” as Shearer explains in the intro to the track, “he also made ’em.” Brooks rounds up the usual suspects, from the angry conservative who appears to have dialed the wrong station to the caller whose radio is turned up too loud, producing feedback. But he also throws a few absurdist curveballs, including a call from a disc jockey who does comedy on the side and wants Brooks’s advice on techniques such as delivery, to which the comedian responds, “Well, I think you can pick it up yourself, can’t you?”

Then there’s the similarly titled “Phone Call to Americans,” a patriotic number for country stations to play in anticipation of America’s bicentennial. Inspired by spoken-word fluke hits like Victor Lundberg’s “An Open Letter to My Teenage Son” (1967) and Byron MacGregor’s “Americans” (1973), Brooks’s mawkish history lesson — before it metamorphoses, that is, Lon Chaney Jr. style, into an illogical rant that Donald Trump might appreciate (“We play ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ at ball games, but still one team always loses”) — may have even inspired A Star Is Bought narrator Charlie Van Dyke, who released his own patriotic single, “The Flag,” the following year.

Brooks also targets classical-music stations, on the track “Love Song,” by adding newly unearthed lyrics to Ravel’s Boléro (“Do you like children? / You do? / Well, guess what, my dear? / You’ll be getting none from me / I’ve undergone some surgery / There’ll be no pregnancy here / I’m about as potent as a warm glass of beer”), accentuating the comedy-as-symphony motif that makes “Phone Calls From Americans,” “The Albert Brooks Show,” and “Party From Outer Space” such fun to listen to.

The last of those three tracks may be a symphony made with broken toy instruments, but that’s the source of its charm. It’s a novelty song in the vein of Bill Buchanan and Dickie Goodman’s 1956 hit “The Flying Saucer” or Goodman’s “Mr. Jaws,” released the same year as A Star Is Bought, that repurposes snippets of popular songs as “answers” to a reporter’s questions (Chris Rock brought hip-hop into the fold of this peculiar subgenre with “Press Conference,” from his 1997 album Roll With the New). But in Brooks’s case, all of the popular songs are fakes he’s written himself so that he won’t have to pay royalties if “Party From Outer Space” becomes a Top 40 hit.

Harry Nilsson can be heard as “Lassie” (the first time around, anyway — Andrew Gold, who’s credited on A Star Is Bought‘s back cover with arranging the fakes, may be the famous collie near the end of the track); Linda Ronstadt, who dated Brooks during the two-year gap between Comedy Minus One and A Star Is Bought, is “Al Jolson”; and Micky Dolenz, a fellow friend of Nilsson and John Lennon’s during the latter’s 18-month “lost weekend” in L.A., seems to be the one singing “no no no” when asked if he’s a celebrity. Harry Shearer’s golden throat makes its presence known as well.

A Star Is Bought also includes behind-the-scenes tidbits and testimonials offered up by Ronstadt and Dolenz in addition to Peter Tork, Alice Cooper, Rob Reiner, “Auto Club president Herman Miller,” and future billionaire David Geffen, who mixes love and capitalism, as any pop-song-shilling label president worth his salt must, when he asks, “If you loved me, don’t you think you could cough up a list price of $6.98 or $7.98 for my tape? I think you would.”

There are even jokes built into the structure of those tidbits and testimonials: After Reiner says, “In high school we used to make fun of Albert for listening to FM radio because we thought it was a sissy thing to do,” Charlie Van Dyke cuts into his prerecorded sound bite to introduce the actor-director as “childhood friend Rob Reiner,” just as he cuts into almost every other sound bite on the album after the speaker’s first sentence. Reiner doesn’t need a second one, though: “No no no, don’t come back to me — that’s all I have to say about it.”

And there’s the die-cut stand built into the back cover in case you want to display the album’s jacket, which has room on the front cover for a “personally autographed” photo of Brooks, on your mantel, bookshelves, or bedside table.

No creative expense was spared on A Star Is Bought or Comedy Minus One. Brooks may have been thought of as a comedian’s comedian in the ’70s, but, judging by his two albums, his style was never hipper-than-thou. He sounds excited to be sharing his comic convictions with listeners — literally, in the case of Comedy Minus One‘s collaborative title track — and because his approach to comedy is inclusive, a listener can fully enjoy that track without knowing it’s a take-off on the Music Minus One series of musical-accompaniment records. (I certainly wasn’t aware of those records until I started writing this piece.) Likewise, the humor of Brooks’s loopy love of country in “Phone Call to Americans” doesn’t require prior knowledge of Victor Lundberg and Byron MacGregor’s abbreviated discographies. Brooks did his homework so that you don’t have to.

No creative expense was spared on A Star Is Bought or Comedy Minus One. Brooks may have been thought of as a comedian’s comedian in the ’70s, but, judging by his two albums, his style was never hipper-than-thou. He sounds excited to be sharing his comic convictions with listeners — literally, in the case of Comedy Minus One‘s collaborative title track — and because his approach to comedy is inclusive, a listener can fully enjoy that track without knowing it’s a take-off on the Music Minus One series of musical-accompaniment records. (I certainly wasn’t aware of those records until I started writing this piece.) Likewise, the humor of Brooks’s loopy love of country in “Phone Call to Americans” doesn’t require prior knowledge of Victor Lundberg and Byron MacGregor’s abbreviated discographies. Brooks did his homework so that you don’t have to.

Two years before Comedy Minus One landed in record stores — before landing on Sunset Boulevard, of course — Esquire commissioned Brooks to write an article. He came up with “Albert Brooks’ Famous School for Comedians,” a riff on the Famous Artists School correspondence courses. As editor Lee Eisenberg described it in the magazine, “Albert came to New York to work it out, and we put our offices at his disposal. He took complete control of the photography, he was exceptionally meticulous and hard to please with written copy. But we hope we gave him what he wanted.” (Esquire has since updated the original article with contributions from Bob Odenkirk and David Cross, in 2002, and Patton Oswalt, in 2015.)

PBS then commissioned Brooks, in 1973, to adapt the article as a short film for its series The Great American Dream Machine, which in turn led to the films he made for Saturday Night Live, where he was viewed “as a niggling perfectionist who went over-budget on his films (Brooks denies this) and who demanded constant attention,” according to Doug Hill and Jeff Weingrad’s book Saturday Night: A Backstage History of Saturday Night Live (1986). Longtime SNL producer Lorne Michaels confirmed that sentiment when he told Paul Slansky, in 1979 for The Village Voice, “We couldn’t edit, we couldn’t have audience laughter on the soundtrack. He had complete creative control.”

But, as Harry Shearer told Slansky, “One of the ways Albert is smarter than most of the people in the business is that he’s held out for total control over the things that are important to him.” It can be a blessing and a curse to truly care about your work, because not everyone you work with will feel the same way. Brooks illustrates this point perfectly in a scene from Modern Romance (1981), his second feature film as a director: his character, Robert Cole, is a film editor who needs a sound effect of “pounding” footsteps for a particular shot in the science fiction film he’s working on, but the sound editors he’s forced to ask for help (Brooks’s older brother Cliff Einstein plays one of them) couldn’t care less. In the end, because he wants it done right, he has to do it himself.

Shearer cowrote Brooks’s directorial debut, the mockumentary Real Life (1979), with Brooks and Monica Johnson, but he explained last year on comedian Marc Maron’s podcast, WTF, that he had a falling-out with Brooks after finishing the script. Shearer himself has been known to ruffle feathers, not only during one and a half nonconsecutive seasons on Saturday Night Live (1979-’80, ’84-’85) — when he left the second time, in January 1985, he chalked it up to creative differences, telling a reporter, “I was creative and they were different” — but also as a, well, vocal member of the voice cast of The Simpsons (1989-present) — he quit that series last May over a contract dispute before returning two months later. When Maron asked him for his take on why he’s been deemed difficult, Shearer responded, “It’s what happens if you think you know what you want and you are determined to get it.”

Paul Slansky’s article for Playboy mentions that Brooks and Shearer did collaborate again after Real Life — on the radio. In October 1982 Brooks spent a week filling in for a morning DJ in Phoenix (one who could take a joke about his profession, obviously) and interviewed Shearer, twice, as Ronald Reagan. Slansky wrote that Brooks enjoyed his week in Phoenix so much that he was considering a return to stand-up. It never came to pass, but at least Shearer and he were able to pay their respects one last time, as a team, to one of their first loves. (Brooks has appeared on The Simpsons in guest spots almost from the beginning, and in 2007 he voiced the villain in The Simpsons Movie. “One of the most fun things about the movie was actually working again with Harry Shearer, whom I hadn’t worked with for years and years,” Brooks says in John Ortved’s 2010 book The Simpsons: An Uncensored, Unauthorized History. “That was the high point of the movie for me, just to be in a room with Harry.”)

Brooks, an Oscar nominee for Best Supporting Actor for Broadcast News (1987), has spent the past decade of his career focusing on acting, with dramatic roles in the films Drive (2011), A Most Violent Year (2014), and Concussion (2015). (Although he never graduated, Brooks enrolled in the Carnegie Institute of Technology, now Carnegie Mellon University, in 1965 to study drama, even after Carl Reiner told Johnny Carson and millions of Tonight Show viewers that the funniest people he knew were Mel Brooks and his teenage son’s friend Albert Einstein.) He also wrote his first novel, 2030: The Real Story of What Happens to America (2011), allowing him to explore, in his 60s, another new career path.

In December 1997 The New York Times Magazine ran a story by David Handelman about the alumni of The Ben Stiller Show, which had been canceled by Fox almost five years earlier after just 13 episodes; nearly everyone associated with the show, from Stiller and fellow cast members Andy Dick, Janeane Garofalo, and Bob Odenkirk to writer David Cross and executive producer Judd Apatow, had gone on to land bigger projects on TV and in movies. “What we had in common was we all thought Albert Brooks was the funniest person on the planet,” said stand-up comic Dana Gould, who’d appeared on Stiller’s show in various sketches. “We all wanted to become him, to write and direct and act in really harshly funny movies.”

Brooks had kind words for the younger comedians, but he was realistic about their chances of reinventing the wheel: “If we can smarten things up, we’re only going to do it a little bit. As long as there are humans, and McDonald’s, the Three Stooges will always reign.” But as long as copies of Comedy Minus One and A Star Is Bought are still in circulation — someway, somehow — there’s hope for the future.

Rhino’s 1993 CD reissue of Comedy Minus One is out of print, while A Star Is Bought has never been reissued, allegedly because Brooks owns the rights and isn’t interested. But I found a ripped-from-vinyl version on a blog almost six years ago and a promotional copy in a record store about three years ago, so maybe you’ll get lucky too.

Comments