There’s something a bit bizarre about commending one to rest in peace after their lifetime of chronicling the ruin of the un-peaceful undead. But that’s where we find ourselves in the situation of Bernie Wrightson. Many will know the name, thanks to his decades of work in comics, but many more won’t, and will only recognize his style: rounded, fluid, detailed, grotesque, but so ornate that — even in your moments of repulsion — you have to give Wrightson credit for the craft.

There’s something a bit bizarre about commending one to rest in peace after their lifetime of chronicling the ruin of the un-peaceful undead. But that’s where we find ourselves in the situation of Bernie Wrightson. Many will know the name, thanks to his decades of work in comics, but many more won’t, and will only recognize his style: rounded, fluid, detailed, grotesque, but so ornate that — even in your moments of repulsion — you have to give Wrightson credit for the craft.

And such craft. His groundbreaking illustrated version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein novel set a standard so high that artists who followed either had to follow close behind or give up altogether. One look at his plates for the book lets you know that Kenneth Branagh must have used Bernie’s vision to inform his cinematic version, played by Robert DeNiro.

And such craft. His groundbreaking illustrated version of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein novel set a standard so high that artists who followed either had to follow close behind or give up altogether. One look at his plates for the book lets you know that Kenneth Branagh must have used Bernie’s vision to inform his cinematic version, played by Robert DeNiro.

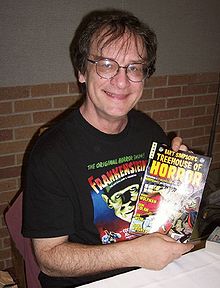

As legend has it — Bernie loved legends — he taught himself how to draw out of the E.C. comic books in the late ’50s, the sometimes shocking horror and science fiction releases that would eventually set off a firestorm of controversy. That in turn fueled the introduction of the Comics Code Authority which dictated certain rules of conduct and decency — rules that Wrightson and his co-creators gleefully subverted.

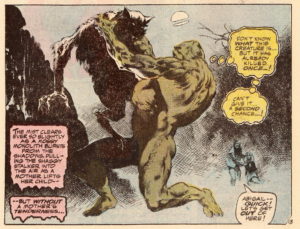

One of those co-creators, Len Wein, helped bring shape to a shambling monster borne from the swamp. He was once a man named Alec Holland but under Wein and Wrightson’s unique vision, Swamp Thing was wrought. One more co-creator was yet another devotee of the E.C. world, and with director George Romero in the drivers’ seat, Wrightson and Stephen King added the nasty chemicals that coursed through the open veins of Creepshow.

One of those co-creators, Len Wein, helped bring shape to a shambling monster borne from the swamp. He was once a man named Alec Holland but under Wein and Wrightson’s unique vision, Swamp Thing was wrought. One more co-creator was yet another devotee of the E.C. world, and with director George Romero in the drivers’ seat, Wrightson and Stephen King added the nasty chemicals that coursed through the open veins of Creepshow.

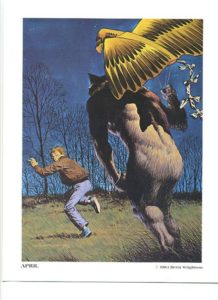

Very recently the print company Nakatomi Inc. released a portfolio of the artwork Wrightson did for King’s novella Cycle Of The Werewolf. Funded through a Kickstarter campaign, Wrightson told the story of how he planned to create this ornate and dread-filled calendar, completed with small pieces of text from King. The publishers wanted more than that, and eventually, the novella came to be. It eventually was adapted to the film Silver Bullet. Wrightson’s videos for the campaign never revealed in full how ill he’d been.

Very recently the print company Nakatomi Inc. released a portfolio of the artwork Wrightson did for King’s novella Cycle Of The Werewolf. Funded through a Kickstarter campaign, Wrightson told the story of how he planned to create this ornate and dread-filled calendar, completed with small pieces of text from King. The publishers wanted more than that, and eventually, the novella came to be. It eventually was adapted to the film Silver Bullet. Wrightson’s videos for the campaign never revealed in full how ill he’d been.

Cancer again.

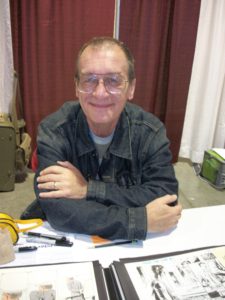

There’s something that the videos did reveal, something that most comics creators knew as yet another part of his — there’s that word — legend. Bernie was a gentleman, emphasis on gentle. Other creators would cite his kindness and mentoring, his love for the work and his enthusiasm. There are a lot of shining stars in the comic book universe, but few were as loved as Bernie, and few were as open-hearted as Bernie. Somehow he was able to stay above the sometimes very nasty world of politics of the comic book world. He was taken advantage of too, stuck in the hell of losing original artwork due to unscrupulous contracts, and the legal hell of trying to get them back. In some circumstances, his work was thrown away. “The story’s been printed,” so they’d say. “Why would anyone want the originals?”

There’s something that the videos did reveal, something that most comics creators knew as yet another part of his — there’s that word — legend. Bernie was a gentleman, emphasis on gentle. Other creators would cite his kindness and mentoring, his love for the work and his enthusiasm. There are a lot of shining stars in the comic book universe, but few were as loved as Bernie, and few were as open-hearted as Bernie. Somehow he was able to stay above the sometimes very nasty world of politics of the comic book world. He was taken advantage of too, stuck in the hell of losing original artwork due to unscrupulous contracts, and the legal hell of trying to get them back. In some circumstances, his work was thrown away. “The story’s been printed,” so they’d say. “Why would anyone want the originals?”

You tell me. The nice guy, Bernie Wrightson, finished first. He exorcised his demons through the work. We are better, though nonetheless tormented, for it.

Comments