To Popdose Readers: My apologies for not having noticed that some of you have been sending me comments on the web site. Jeff pointed out that I could see them right below the text, and I wanted to say thanks for the interesting messages. I will try to answer as many as I can individually from this point on, now that I know where to find them. I’ll also try to publish one installment per week. The past few weeks have been clean-up time here in the Berkshires, and I’ve been playing pick-up-sticks after a pretty serious winter. Next week I’ll be playing golf in the desert with a bunch of ancient record execs, managers and even a couple of musicians. After that, I’ll do my best to settle in at one installment each week. Thanks for your patience.

From my perspective inside the label, it was both fascinating and ridiculous to see the change in how I was assessed by my colleagues after Ted’s first LP went platinum in a matter of months. I’d be toiling at the label for five years, trying to sign bands, doing edits for single releases, and evaluating thousands of live performances and tape submissions. Now in a matter of weeks, it was suddenly “You’re beautiful, babe.” Traditionally, there has been so little consideration for prior accomplishments and accumulated experience in the record business that it really does come right down to “What have you done for me this week?”

I certainly hadn’t spent five years at Epic hiding or being shy, and I believe there was plenty of opportunity during that period for my colleagues to assess my musical judgment and taste; but now that I had accomplished something that improved everyone’s lot at the label, there was a rather abrupt change in the way people regarded me. One hit album made me a seasoned expert in the eyes of many in the music business — because I had both signed and co-produced this new artist. Of course, Ted’s opening slot on the Aerosmith tour and his new aggressive management by the Leber-Krebs organization certainly didn’t hurt album sales, but this was plain enough for everyone to see. Still, I had a new-found clout that was palpable. Suddenly the label was interested to know whom I would produce next.

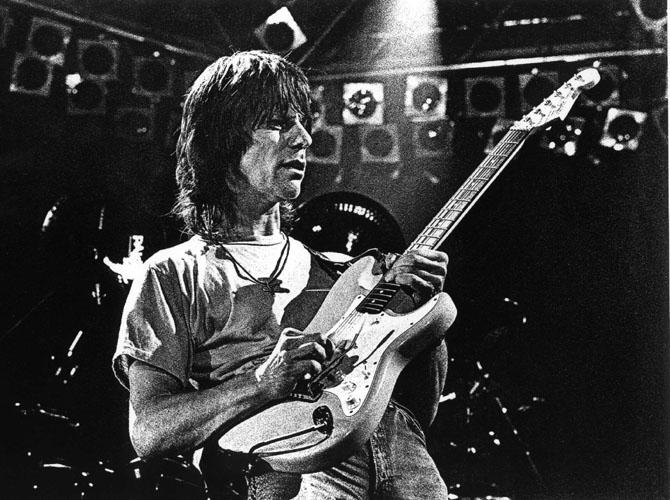

Jeff Beck was an Epic act with whom I was familiar as a result of my being the A&R liaison with our British artists, who also included Argent, the Hollies and Argent’s lead singer, Colin Blunstone. I had spent some time with Jeff at his home outside London, where he showed me his hotrod collection and we played some snooker in the game room. Since the Yardbirds, Jeff was pretty much a solo act, and when he played live, it was usually with other well-known musicians (Carmine Appice, Tim Bogert, Rod Stewart, etc.).

Jeff Beck was an Epic act with whom I was familiar as a result of my being the A&R liaison with our British artists, who also included Argent, the Hollies and Argent’s lead singer, Colin Blunstone. I had spent some time with Jeff at his home outside London, where he showed me his hotrod collection and we played some snooker in the game room. Since the Yardbirds, Jeff was pretty much a solo act, and when he played live, it was usually with other well-known musicians (Carmine Appice, Tim Bogert, Rod Stewart, etc.).

When he teamed up with keyboardist Jan Hammer, they decided to do a live album, and I was assigned to oversee the project. This involved recording five or six nights in several cities, and then evaluating the recorded material to determine the best performance of each song. In order to do this properly, I had to have over 50 rough mixes, and Jeff wanted to fix up quite a few of his tracks before we compared them.

We decided to go into Allen Toussaint’s Sea-Saint Studios in New Orleans while Jeff was performing there. We spent the better part of a day with a house engineer and about 10 cartons of two-inch tape. It was a big job, so I had made notes regarding the sections I thought needed repair. After a few takes, Jeff told me to just get him in (start recording) wherever I could, and he’d do his best to play along. We spent about five hours with me operating the tape machine and Jeff playing. I would give him the high sign when I was going to punch the “record” button, and he’d start playing. We made great progress, and I remember wishing my friends could see me now, “producing” Jeff Beck. I know that Jeff felt pretty comfortable after that day, and I had visions of being credited as the album’s producer if I could oversee the mix. Jan had other ideas.

That night at the hotel restaurant in the French quarter, Jeff’s manager Ernest Chapman, Jeff, Jan and I had dinner and discussed a timeline for completing the album. When the conversation turned toward mixing, Jan said “Either I mix the album or there will be no album,” in a voice not unlike Arnold Schwarzenegger’s. I was bummed. I did wind up with “executive producer” credit, though. If you’re familiar with that Jeff Beck album (Live with Jan Hammer) and you’ve always wondered why the keyboards are too far forward in the mix, now you know.

One of the most memorable moments I had with Jeff was on the second night of the CBS Records Convention at the Grosvenor House Hotel in London, July of 1977. I was responsible for hosting Jeff and his girlfriend, Celia. Each night, there was a full sit-down meal for about 1,000 people, and several CBS acts would perform. Because of Jeff’s importance, we were seated at a table down in front, very near the stage. Clive had always invited a number of very high-profile stars to attend these dinner shows, and the practice continued after he was gone. These shows were really very glittery affairs.

As the three of us chatted over a glass of wine, the assembled guests filed in and took their seats. I saw Mick and Keith take seats facing us at a table about feet away. Mick looked over, broke into a big smile, and with a twinkle in his eye said, “‘Ello, Ceeeee-lia!” Jeff just stared straight ahead, unsmiling. I was left to imagine the significance of this encounter.

A few minutes later, I was stunned to see George and Ringo take seats at the table right next to ours. Later in the evening, fortified by a few more glasses of wine, I saw George get up and walk toward the restroom, so I followed. I waited until he was about to leave (yes, after he had washed his hands), and introduced myself. I remember speaking as quickly as I possibly could, in order to maintain his attention, and I also remember his polite but slightly distracted look. When I started to refer to certain guitar licks, and asked questions about certain solos in the songs that he had written, he focused. We had a pleasant conversation there in the mens’ room of the Grosvenor House, and I’ll never forget it. Unbelievably, I had met and spoken with my favorite Beatle. I could die a happy man.

One day in 1975 I received a phone call in my office from producer Jack Douglas, who had made, in my opinion, the best American rock & roll album to date (Aerosmith’s Rocks). I suspect that Jack had called David Krebs to report on a great new band he had heard, and David probably told him to call me. Jack told me about a band called Cheap Trick from Rockford, Illinois, and how much he was impressed by them. A strong tip from Jack Douglas was enough to get me out to Illinois in a hurry, and the following weekend I saw Cheap Trick play to a packed club at a strip mall in Quincy, Illinois. I returned to New York and once again took Steve Popovich out to see this band. We signed them, and Jack made their first album. During the recording I visited the studio several times, and learned a little more about producing.

One day in 1975 I received a phone call in my office from producer Jack Douglas, who had made, in my opinion, the best American rock & roll album to date (Aerosmith’s Rocks). I suspect that Jack had called David Krebs to report on a great new band he had heard, and David probably told him to call me. Jack told me about a band called Cheap Trick from Rockford, Illinois, and how much he was impressed by them. A strong tip from Jack Douglas was enough to get me out to Illinois in a hurry, and the following weekend I saw Cheap Trick play to a packed club at a strip mall in Quincy, Illinois. I returned to New York and once again took Steve Popovich out to see this band. We signed them, and Jack made their first album. During the recording I visited the studio several times, and learned a little more about producing.

The record did reasonably well for a debut LP, but there were no breakthrough singles. Still, it established them at radio, and we needed a follow-up album. Jack found himself tied up with Aerosmith, who at the time could take many months to complete an album, so Cheap Trick said they would be happy with my producing their second effort. I was delighted at the opportunity, because I enjoyed them personally, they were one of the most musically talented bands I’d ever seen, they were good writers, and they were self-contained. They also had terrific senses of humor.

Just prior to this, I had been asked to produce the first record by a San Francisco artist named Eddie Money on Columbia. He was managed by Bill Graham, and I had already gone out to meet with him and start to get a backing band together for the studio. Bruce Lundvall, who was now the president of CBS Records, intervened in this situation and made it appear that I was drafted by Epic to produce Cheap Trick. This way, we could minimize any wrath that Graham would have directed toward me (and the man could direct some serious wrath).

Eventually, Bruce Botnick produced Eddie’s record and did an excellent job. I was relieved to be working with Cheap Trick instead, as I wasn’t really looking forward to the task of assembling a studio band for Eddie, when I knew next to nothing about the talent pool on the west coast. When Cheap Trick’s manager Ken Adamany told me they wanted to record in Los Angeles, I called Rose Mann, manager of the Record Plant on Third Street, and asked her for some recording engineer suggestions. She gave me the names of five engineers who worked regularly at her studio, and I spoke with them all on the phone. I chose Gary Ladinsky, because I liked the way he sounded, and he didn’t try hard to sell himself. Gary and I wound up making about 15 albums together.

As some Popdose readers may have read some months ago, I enjoyed a new-found freedom during this album project. As a new producer, I would frequently turn to the band after we tried something I suggested, and ask them what they thought of it. More often than not, the reply was “You’re the producer.” So I was able to proceed musically with a freedom that I hadn’t realized before. Ted Nugent basically knew all the parts to all the songs before he even entered the studio; he didn’t love changes, and he wasn’t the kind of guy to sit around and try this and that. Fortunately, he knew what was appropriate for Ted’s music.This restricted the producer’s role to something along the lines of “quality control.” The only way I was free to experiment was to be in the studio mixing without Ted in attendance. This way, a few things happened (particularly on “Stranglehold”) that probably wouldn’t have if Ted had been mixing with us.

This freedom was what led me to help “I Want You to Want Me” go in the direction I honestly felt it wanted to go. It was kitsch. It was light. It was old-fashioned. Bands are big fans of historical revision, and they seem to remember things in a very different way from the way they may have happened. Everyone was happy with the song when it was finished. If they weren’t, they certainly didn’t tell me. Later, of course, the band changed the nature of the song, and that worked well, too.

When I was in Atlanta remixing the second single from In Color (I think it was “Southern Girls”), a Florida manager named Pat Armstrong brought a band into the studio to audition for me. They were big, tough and mean, and the lead guitarist was missing one of his two front teeth. But they also had a very distinctive and charismatic vocalist, a solid bass, a great drummer and a fine guitar trio.

They played some very catchy songs, and did a few lengthy Southern-style guitar jams. At the end of the audition, I told them I thought they were very good, and that I thought we might be able to make some records. The guitarist said over the talkback, “Mr. Werman, I just wanna get my front tooth back.” This was Molly Hatchet, and this time I didn’t have to ask anyone’s permission to sign them. We just did it. Once again, as with Ted Nugent and Cheap Trick, I found it a little curious that no other A&R people had offered this band a deal. They literally walked right into the room and handed me a signing. It had been six years since I had started at Epic Records, and I was finally getting into gear.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=aaed8bf4-8a0d-4ece-b5c8-335e80727988)

Comments