![61OobVqO1pL._SCLZZZZZZZ_[1]](https://popdose.com/wp-content/uploads/61OobVqO1pL._SCLZZZZZZZ_1.jpg) The press kit for Pat Metheny‘s Orchestrion promises that the album “redefines solo performance,” and for once, that isn’t just gently perfumed publicist smoke being blown up your ass — it’s the God’s honest truth. Entranced by the orchestrion, a mechanical instrument array that surfaced in the late 19th century, Metheny enlisted a small army of inventors to help him bring the concept into the modern era. The result is this five-track, 52-minute collection, which finds Metheny quite literally running the show — both as the leader of the mechanical “band,” operated via solenoid switches and pneumatics, and as the master guitarist who’s ruled the jazz airwaves for the last quarter century or so.

The press kit for Pat Metheny‘s Orchestrion promises that the album “redefines solo performance,” and for once, that isn’t just gently perfumed publicist smoke being blown up your ass — it’s the God’s honest truth. Entranced by the orchestrion, a mechanical instrument array that surfaced in the late 19th century, Metheny enlisted a small army of inventors to help him bring the concept into the modern era. The result is this five-track, 52-minute collection, which finds Metheny quite literally running the show — both as the leader of the mechanical “band,” operated via solenoid switches and pneumatics, and as the master guitarist who’s ruled the jazz airwaves for the last quarter century or so.

In theory, it’s pretty amazing stuff — which is why it’s a little disappointing that, on record, Metheny’s one-man-band approach sounds an awful lot like the Pat Metheny Group. Watching him assemble these songs is an undeniable kick — take a look at the below video for proof — but melodically and rhythmically, the orchestrion inspires Metheny in disappointingly subtle ways. Unless you’re really a student of his music, you aren’t going to hear anything here that you haven’t heard from Metheny before; this is, I suppose, a testament to how seamlessly he was able to incorporate his art into such an unusual framework, but once you see all the interesting musical angles that went into its construction, you expect Orchestrion to stick a little on the way down, and its unrelenting smoothness can’t help feeling like a letdown. And yes, “Metheny” and “smooth” go hand in hand — but when you read that an album was recorded with a mechanically operated room full of instruments that includes “several pianos, drum kit, marimbas, ‘guitar-bots’, dozens of percussion instruments and even cabinets of carefully tuned bottles,” well, it’s hard not to expect something a little wild and funky. If you’re a fan, purchase Orchestrion without reservation; if you aren’t, it’s doubtful anything here will change your mind.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/9VymAn8QJNQ" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

If you miss Mazzy Star at their poppiest, or the Sundays at their most intoxicatingly ethereal, you may wish to make the acquaintance of the Mary Dream, a Nashville duo with a firm grasp of the slender thread between smoothly polished melodic pop and ponderous singer/songwriter pap. Their latest, This Kind of Life, was recorded with a deliberate DIY ethic, but you can’t hear it in these 11 tracks; everything about Life sounds just as big, and just as finely crafted, as anything the band could have created with a major label budget. If the Mary Dream has a real flaw, it’s that the underlying darkness that anchors this genre’s best acts is mostly missing here — the album’s all gauze in a cool breeze, and though they have a gift for writing catchy, soothing melodies, it wouldn’t hurt them to come up with a truly unshakable song or two. They’re still an album or two away from their own “Fade Into You” or “Here’s Where the Story Ends,” in other words — but in the meantime, This Kind of Life comes closer than most to claiming the genre’s long-vacant throne.

![517fPy0qRwL._SCLZZZZZZZ_[1]](https://popdose.com/wp-content/uploads/517fPy0qRwL._SCLZZZZZZZ_1.jpg) Some music calls for analysis, some calls for criticism, and some simply asks you to sit, be still, and let it speak to you. The lovely new album from Ali Farka TourÁ© and Toumani DiabatÁ©, Ali and Toumani, falls into the latter category; it’s largely instrumental, and none of its occasional vocals are sung in English, but if you have a functioning soul, you’ll feel it speak to you on a level few pieces of music ever reach.

Some music calls for analysis, some calls for criticism, and some simply asks you to sit, be still, and let it speak to you. The lovely new album from Ali Farka TourÁ© and Toumani DiabatÁ©, Ali and Toumani, falls into the latter category; it’s largely instrumental, and none of its occasional vocals are sung in English, but if you have a functioning soul, you’ll feel it speak to you on a level few pieces of music ever reach.

It’s a record underlined with sadness — this was TourÁ©’s final album, arranged on the fly by DiabatÁ© five years after TourÁ© had ostensibly retired from recording, and everyone knew TourÁ© was in extremely poor health. In fact, he was wracked with pain; the bone cancer that ultimately claimed his life in 2006 made these sessions physically difficult for TourÁ©, to the point that he sometimes had to stop a take. (DiabatÁ© confesses in the liner notes: “At one moment during the sessions I asked myself, ‘Why am I doing this?'”) But in spite of the shadow hanging over the sessions, Ali and Toumani is predominantly a joyful album, one that moves easily from traditional numbers (“BÁ© Mankan,” “Doudou”) back to the TourÁ© repertoire (“Sabu Yerkoy”) and forward into songs chosen on the spot (“Samba Geladio,” “Ruby”).

It’s a hackneyed maxim that music is a universal language, but albums like Ali and Toumani prove its enduring truth — you don’t need to know who TourÁ© was, why he was such a giant, or have even the slightest appreciation for Malian music to feel the warmth and beauty of these performances. They settle on your heart like the sun.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/5ZynyK8FlMM" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

If she’d surfaced in 2002, Meaghan Smith would probably be a huge star — she combines the seemingly effortless sultriness of Norah Jones with the sweet Anita O’Day/Doris Day retro appeal of Nellie McKay, without succumbing to Norah’s sleepiness or giving off McKay’s “crazy lady on the subway you’d chew off your own arm to get away from” vibe. Unfortunately, Smith’s just now getting around to releasing her full-length debut, and no matter how good it is (and it’s very, very good), she’s never going to be able to avoid comparisons with the dozens of chanteuses already on the scene.

As injustices go, I suppose this is fairly minor, but it’s still a little heartbreaking; although The Cricket’s Orchestra almost sounds like a ’40s radio broadcast in spots, Smith’s antique aesthetic never feels like a pose. She comes across as someone who’s honestly fond of (and deeply familiar with) this type of music — and as a result, when she mixes things up with turntable scratches and warped Chamberlain-style strings (“Little Love”), it sounds like a fresh twist instead of a cheap stunt. It’s a bewitching album — and I say this as someone who’s had to review many of the lukewarm efforts released by vaguely jazzy female singer/songwriters over the last seven years, so even if you think you’ve had more than your fill of the Norahs and Nellies of the world, you may wish to make an exception for Meaghan Smith. I’m certainly glad I did.

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/WswYxUrwsRY" width="600" height="344" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

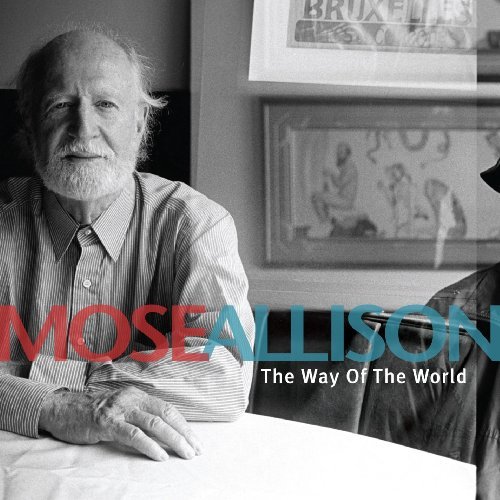

For as long as the record industry has existed, it’s been one of the most magnificent bullshit factories on the planet, but here’s a great example of how splendidly fucked up the business has become: Mose Allison, jazz icon and national treasure, is releasing his latest album on a splinter imprint of the label founded by Bad Religion’s Brett Gurewitz. Don’t get me wrong, I’m overjoyed that the 82-year-old Allison has more music for us, but an artist of his stature should be far too expensive for a boutique outfit like Anti-. Of course, the same is true for other stellar Anti- artists like Mavis Staples, Tom Waits, and Joe Henry — but remember what I was saying about bullshit factories? Let’s just all thank our lucky stars that at least one label seems to be making money with real music.

For as long as the record industry has existed, it’s been one of the most magnificent bullshit factories on the planet, but here’s a great example of how splendidly fucked up the business has become: Mose Allison, jazz icon and national treasure, is releasing his latest album on a splinter imprint of the label founded by Bad Religion’s Brett Gurewitz. Don’t get me wrong, I’m overjoyed that the 82-year-old Allison has more music for us, but an artist of his stature should be far too expensive for a boutique outfit like Anti-. Of course, the same is true for other stellar Anti- artists like Mavis Staples, Tom Waits, and Joe Henry — but remember what I was saying about bullshit factories? Let’s just all thank our lucky stars that at least one label seems to be making money with real music.

Joe Henry, as it turns out, also deserves thanks for The Way of the World — not only did he bring his impeccable (and Grammy-winning) production skills to the album, he coaxed its very existence out of Allison via a letter-writing campaign that slowly convinced the elder statesman to end his 12-year recording hiatus. At this point, Allison’s been around so long that it’s difficult to separate his work from the many influential imprints it’s left on artists as far-flung as Van Morrison, Elvis Costello, and the Pixies; playing one of his records can be a little like sitting in a room full of echoes. Kudos to Henry, then, for cutting straight through to the heart of the matter — namely, Allison holding court at his piano, bringing his proudly weathered voice to bear on a dozen songs whose musical economy is matched only by their sharp wit. As a lyricist, Allison’s always been capable of drawing blood without breaking a sweat, and he hasn’t dulled a bit — look no further than “Modest Proposal” for proof. He does seem to have mellowed a bit, coming across as more of a sage, slightly grumpy grandfather than the dapper misanthropist who graced the cover of Ever Since the World Ended 23 years ago, but this is not a bad thing. Neither, if you hadn’t already guessed, is The Way of the World. Pre-order your copy today.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=e9b89bfb-5071-4cbb-b583-70baeeb35323)

Comments