Last weekend I had dinner with a friend who recently has been surprised to find the ideological ground shifting beneath his feet. A libertarian at heart — fiscally conservative, socially liberal, somewhat obsessed with ”freedom” (whatever that is) — he has voted Republican far more often than Democratic. Two years ago he became enamored of the burgeoning tea-party movement because he reviled President Obama and Congress’s plans to spend untold billions on stimulus and healthcare, and especially because he loathed the collusion between politicians and the banks that had tanked the economy in 2008.

More recently, though, he has watched as the tea party’s initial focus has been diluted by religious-right social activism and endless I-hate-Obama partisanship, and as its objectives have been co-opted by the business interests that dominate the Republican Party. While Ron Paul remains his favorite Republican candidate, he finds that his biggest complaint about Obama these days is that the president is too much of a ”corporatist” to rise to our current challenges — language that belongs more to Ralph Nader than to the eyebrow-enhanced Paul. And, perhaps most surprising, over the last few weeks he has become an ardent cheerleader for the Occupy Wall Street movement. He likes its focus on corporate misbehavior, an emphasis he wishes the tea party hadn’t abandoned, and says he hopes OWS might somehow break business’ stranglehold over policymaking.

More recently, though, he has watched as the tea party’s initial focus has been diluted by religious-right social activism and endless I-hate-Obama partisanship, and as its objectives have been co-opted by the business interests that dominate the Republican Party. While Ron Paul remains his favorite Republican candidate, he finds that his biggest complaint about Obama these days is that the president is too much of a ”corporatist” to rise to our current challenges — language that belongs more to Ralph Nader than to the eyebrow-enhanced Paul. And, perhaps most surprising, over the last few weeks he has become an ardent cheerleader for the Occupy Wall Street movement. He likes its focus on corporate misbehavior, an emphasis he wishes the tea party hadn’t abandoned, and says he hopes OWS might somehow break business’ stranglehold over policymaking.

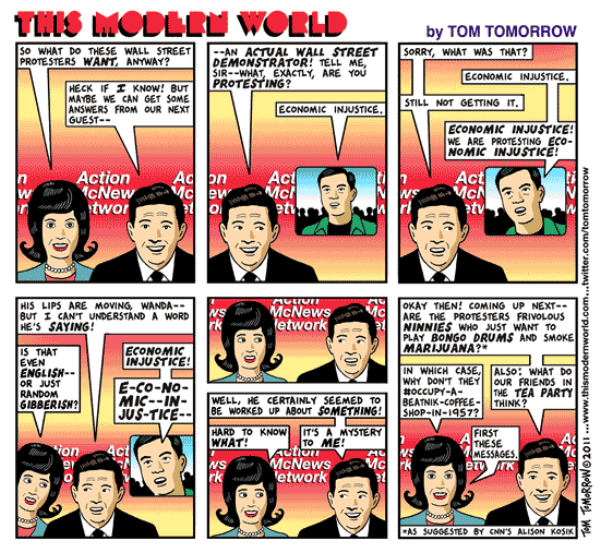

My friend, in all his mixed-up glory, is on to something. When you listen to the mainstream media, you don’t hear much sympathy from tea party supporters for Occupy Wall Street, or vice versa. But ever since OWS began a month ago as a few dozen people refusing to leave a downtown park, I’ve found myself wondering, why not? Might these two groups find areas of common interest on which they can work together? And if they could do that, how much might they accomplish that neither side can hope to achieve alone?

On the surface, the goals of the tea party (such as they have become) and Occupy Wall Street (amorphous as they remain) couldn’t be more different. Tea partiers, after sublimating their early anti-bailouts focus, have targeted their furor in a more traditional, anti-Washington direction — albeit with newfangled ”constitutional” trappings and an amped-up concern for deficits and debt. OWS, on the other hand, is chiefly concerned with those Americans (middle class and otherwise) who are left out of the tea party’s calculus: The millions whose ambitions and earning potential are being thwarted by a system that demands a smarter workforce, but doesn’t create enough (or good-enough) jobs to enable college graduates to pay off their student loans. The homeowners who were pushed into suspect mortgages during the go-go ’00s, then weren’t bailed out when the banks were. And the millions whose livelihoods have been threatened by corporations that enrich executives and shareholders while cutting “head count” and benefits, sending jobs overseas, and gaming the government to minimize their tax burdens and avoid accountability for their screw-ups.

On the surface, the goals of the tea party (such as they have become) and Occupy Wall Street (amorphous as they remain) couldn’t be more different. Tea partiers, after sublimating their early anti-bailouts focus, have targeted their furor in a more traditional, anti-Washington direction — albeit with newfangled ”constitutional” trappings and an amped-up concern for deficits and debt. OWS, on the other hand, is chiefly concerned with those Americans (middle class and otherwise) who are left out of the tea party’s calculus: The millions whose ambitions and earning potential are being thwarted by a system that demands a smarter workforce, but doesn’t create enough (or good-enough) jobs to enable college graduates to pay off their student loans. The homeowners who were pushed into suspect mortgages during the go-go ’00s, then weren’t bailed out when the banks were. And the millions whose livelihoods have been threatened by corporations that enrich executives and shareholders while cutting “head count” and benefits, sending jobs overseas, and gaming the government to minimize their tax burdens and avoid accountability for their screw-ups.

The vague outcomes sought by OWS — a more equitable carving up of the economic pie, and a society that values the well-being of the 99 as well as the 1 — would doubtless require a slew of new taxes on the wealthy, new spending to alleviate poverty, new policies aimed at improving the lots of everyone from illegal immigrants to folks whose mortgages are under water, and new regulations that limit corporations’ ability to (generally speaking) forsake the public interest in pursuit of grotesque profits. All of which are anathema to the tea party, of course.

Let’s face one important fact: In the previous two paragraphs, you could replace every instance of the phrases ”tea party” and ”Occupy Wall Street” with the words ”conservative” and ”liberal,” and you’d have a fair summation of the ideological chasm that has driven American debate since 1932. Considering the polarization that bogs down our politics, and the near death of compromise as an acceptable policy outcome, it’s difficult to imagine that a tea party-OWS coalition might agree on solutions to the policy issues that vex us.

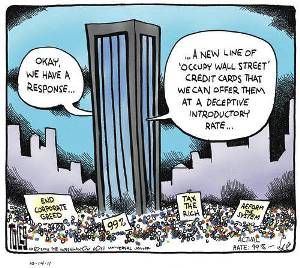

However, there’s one key trait that links the two movements — one that just might extract us from our corporate/banking/political quagmire — and that is their anti-establishment roots. Tea partiers haven’t been afraid to challenge moderate politicians favored by the GOP poobahs, and tea party congressmen have been giving John Boehner fits all year. Meanwhile, OWS has emerged from the populist left, and the Obama administration has no clue how to harness it — not after turning healthcare reform into an insurance-lobby giveaway, turning the SEC and Justice Department’s attention away from dozens of Wall Street criminals, and giving away most of the store on Dodd-Frank in order to appease the banking interests who funded Obama in ’08. (New York Fed alum Timothy Geithner doesn’t have a populist bone in his body, anyway.)

However, there’s one key trait that links the two movements — one that just might extract us from our corporate/banking/political quagmire — and that is their anti-establishment roots. Tea partiers haven’t been afraid to challenge moderate politicians favored by the GOP poobahs, and tea party congressmen have been giving John Boehner fits all year. Meanwhile, OWS has emerged from the populist left, and the Obama administration has no clue how to harness it — not after turning healthcare reform into an insurance-lobby giveaway, turning the SEC and Justice Department’s attention away from dozens of Wall Street criminals, and giving away most of the store on Dodd-Frank in order to appease the banking interests who funded Obama in ’08. (New York Fed alum Timothy Geithner doesn’t have a populist bone in his body, anyway.)

The GOP establishment may have succeeded recently in distracting tea partiers’ ire away from the banks, but that movement’s ”big bang” remains the TARP legislation of 2008, which revealed the unholy alliance between the government and financial institutions — a cesspool of lobbying and shady deals, with execs lining up to pass through an incestuous revolving door linking Wall Street, K Street, and the Treasury Department. The bank bust and TARP — plus three years of watching Congress fail to make economic progress with its lame half-measures, watching business rake in record profits while refusing to re-invest, and watching the nation’s income disparity grow more and more obscene — have now served as the ”big bang” for OWS, as well.

The root of all those evils — and the issue on which the anti-establishment twain just might meet — is the confluence of money and politics. It’s time to recognize that the damage done to American democracy by our pay-to-play system of campaign financing and interest-group lobbying, which first exploded during Watergate, is at a similar crisis point now — exacerbated by the Supreme Court’s absurd, plutocratic decision in the Citizens United case. We actually may be in an even worse place than Watergate, because it’s not simply an administration that’s on the verge of going down. It’s our entire economy.

We The People occasionally rise up on Election Day and believe we have overturned the political order — in fact, it’s happened twice in the last five years — but then we watch helplessly as our politicians and business leaders resume their mutual lap dance. It’s an arrangement that benefits incumbents in both parties who have elections to win, sweetheart deals and earmarks to offer, and little time to make up their own minds on the issues of the day … much less write their own bills to police the financial and industrial sectors. It benefits the banking and corporate elites — and occasionally, depending on who holds power, the labor unions and various interest groups — who have money to burn on campaign contributions and lobbyists, and who are constantly in search of ways to leverage that cash to manipulate lawmakers. And it benefits … just about nobody else. Not the working class, certainly. And, these days, not even the middle-class families once so fetishized by politicians from Reagan to Clinton.

We The People occasionally rise up on Election Day and believe we have overturned the political order — in fact, it’s happened twice in the last five years — but then we watch helplessly as our politicians and business leaders resume their mutual lap dance. It’s an arrangement that benefits incumbents in both parties who have elections to win, sweetheart deals and earmarks to offer, and little time to make up their own minds on the issues of the day … much less write their own bills to police the financial and industrial sectors. It benefits the banking and corporate elites — and occasionally, depending on who holds power, the labor unions and various interest groups — who have money to burn on campaign contributions and lobbyists, and who are constantly in search of ways to leverage that cash to manipulate lawmakers. And it benefits … just about nobody else. Not the working class, certainly. And, these days, not even the middle-class families once so fetishized by politicians from Reagan to Clinton.

Just as, two years ago, the more conservative among those middle-class voters gravitated toward the tea party, right now the more progressive ones are getting ginned up over OWS. Each group wants a profoundly different outcome — but neither is going to get anywhere near it as long as Washington and Wall Street continue to 69 on the other side of a very pricey peephole.

Considering the current Supreme Court’s antagonism toward middle-class interests, even a broad-based alliance between tea partiers and OWS types is unlikely to forge real campaign-finance reform — at least not without a constitutional amendment that bans large donations and institutes strict public-financing rules. (As anyone who watched Ken Burns’ Prohibition documentary knows, fomenting support for such an amendment from the grass roots is possible, but can require decades of struggle.) In the meantime, though, both sides working together might use their populist strength — and the power of the primary election — to force lawmakers into implementing outright bans on gifts, junkets, plane rides and other goodies provided by lobbyists, and also into disbanding their own political action committees and unilaterally rejecting campaign funds from corporations and special-interest PACS, if not big checks entirely.

Getting big money out of politics certainly appeals to OWS activists, who seek to deny corporations their current kung-fu grip over our legislative process. It should also appeal to tea partiers, who repeatedly express interest in curbing the power of incumbency and who insist that politicians ”listen to the American people.” If these two groups could recognize this shared interest, perhaps their joined forces could remake American campaigns and governance, and restore a modicum of political power to the masses. Then they could go back to ideological war, and let the most convincing arguments (rather than the most cash-infused candidates) win.

Will it ever happen? Probably not. Too many Americans have their ideological blinders too firmly attached to find common ground on even this one issue. And asking the voting multitudes to see through the Matrix of money and power in Washington is like asking the entire nation to subscribe to the Utne Reader. It’s one thing for the tea party base to push back so instinctively against the corporatist Mitt Romney that even Herman Cain can lead the polls; it’s another thing to imagine them joining forces with folks they’re currently mocking with calls to ”put down the bongo drums and get a job.” And those crowds in Lower Manhattan might relocate en masse to Denmark before they’d make a deal with that rabble who get off on depicting their president with a bone through his nose.

Will it ever happen? Probably not. Too many Americans have their ideological blinders too firmly attached to find common ground on even this one issue. And asking the voting multitudes to see through the Matrix of money and power in Washington is like asking the entire nation to subscribe to the Utne Reader. It’s one thing for the tea party base to push back so instinctively against the corporatist Mitt Romney that even Herman Cain can lead the polls; it’s another thing to imagine them joining forces with folks they’re currently mocking with calls to ”put down the bongo drums and get a job.” And those crowds in Lower Manhattan might relocate en masse to Denmark before they’d make a deal with that rabble who get off on depicting their president with a bone through his nose.

What’s more likely is that, just as the tea party is slowly but surely being subsumed within the GOP, Occupy Wall Street eventually will become the activist arm of the Democratic Party. Lawmakers will pay increased lip service to the populism on both sides, while continuing to rake in dollars and watered-down drinks from the corporations, banks and special interests who really control our politics. In exchange, we’ll continue to get watered-down domestic legislation that can’t break a filibuster, and wouldn’t really change anything if it did. And the rich will get richer, and the middle class will shrivel like Barry Bonds’ balls.

Somebody, please, prove me wrong.

Comments