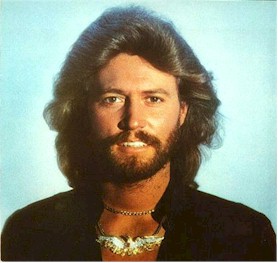

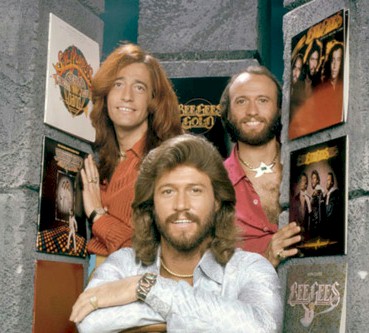

There’s an aesthetic dissonance in listening to late-Seventies-era Barry Gibb sing something like “Love You Inside Out,” or “Tragedy,” or “Stayin’ Alive” or any one of the other songs in which he hits the highest of the high registers and threatens to break any nearby glass with the power of his manly sympathetic resonance. I mean, just look at him. Look at him. The man had sexual potency oozing out of every pore in his body, like so much sap from a stripped maple; it clung to his ruddy skin and ample chest hair and drove the ladies mad with an almost cosmic-level lust. The abundance of testosterone in his system could actually alter the distribution of same in any man who stood close to him for long enough, as evidenced by the profusion of hair on Robin’s noggin in the band’s golden era, as well as poor Maurice’s lack.

There’s an aesthetic dissonance in listening to late-Seventies-era Barry Gibb sing something like “Love You Inside Out,” or “Tragedy,” or “Stayin’ Alive” or any one of the other songs in which he hits the highest of the high registers and threatens to break any nearby glass with the power of his manly sympathetic resonance. I mean, just look at him. Look at him. The man had sexual potency oozing out of every pore in his body, like so much sap from a stripped maple; it clung to his ruddy skin and ample chest hair and drove the ladies mad with an almost cosmic-level lust. The abundance of testosterone in his system could actually alter the distribution of same in any man who stood close to him for long enough, as evidenced by the profusion of hair on Robin’s noggin in the band’s golden era, as well as poor Maurice’s lack.

That a man endowed with such sexual energy was most famous for singing dance songs like a countertenor lost in the Studio 54 balcony is sufficiently surprising (though it shouldn’t be—Robert Plant got laid plenty by doing the same thing to amped-up blues songs). The truly stunning part was how well that aesthetic dissonance worked, particularly given the often extreme dramatic context of the Bee Gees’ songs. Need an example? Just a little sample? I give you these lines from “Love You Inside Out”:

No man on earth

Can stand between my love and I

And no matter how you hurt me

I will love you ’til I die

Just read that, for a moment, divorced from the sound of the song you know. This is a proclamation (actually, two), a statement made from the mountaintop, with a strong wind blowing a teeming rain, smack into his beard-protected face, with lightning flashing all around him, and thunder threatening to crack the night into small pieces. “No man on earth can stand between my love and I!” he should exult in the voice of Zeus. “I will love you ’til I die!” The valley below should rattle with the echo of his lusty exclamation!

Just read that, for a moment, divorced from the sound of the song you know. This is a proclamation (actually, two), a statement made from the mountaintop, with a strong wind blowing a teeming rain, smack into his beard-protected face, with lightning flashing all around him, and thunder threatening to crack the night into small pieces. “No man on earth can stand between my love and I!” he should exult in the voice of Zeus. “I will love you ’til I die!” The valley below should rattle with the echo of his lusty exclamation!

But … in reality, not so much. No Zeus. No thunder. No rain in the beard. Instead, Gibb mewls the lines like a puddy-tat begging for Whiskas. This is a proclamation? This is unbridled manliness? This is— This is sexy?

Goddamn right it is.

So many of the Bee Gees’ best and best-known songs likewise seem like mountaintop pronouncements, fire-and-brimstone sermons on the dance floor, lyrics shot through with gotta-get-this-out-cuz-if-I-don’t-I’m-gonna-die urgency. Think of the second verse of “Stayin’ Alive” (“Well now I get low and I get high / And if I can’t get either, I really try / Got the wings of heaven on my shoes”), or the music and arrangement of “If I Can’t Have You” (either their own version or Yvonne Elliman’s), or the verses and pre-chorus of “Nights on Broadway”)—each is chilling in its own way, and each features that falsetto, whether as punctuation (like in “Nights'” chorus) or the whole enchilada (um … the rest of them). There were so many of those songs—and so many of them were so great—the aesthetic dissonance was reduced to nil. What was left was great music—great, era-defining music, music that meant as much to the disco era as those first Beatles records did to the British Invasion.

By the time 1979 rolled around, disco’s wave had crested, but the Gibb brothers were still the biggest band on earth. You could certainly dance to the tracks on Spirits Having Flown, but getting would-be Travoltas and Gorneys to strut their stuff under the mirror ball was no longer the raison d’etre of the band’s music. In its place was a purely pop mission, taking that urgency that was their hallmark and churning out as many great potential pop singles as they could. And boy, did they ever succeed.

Everybody knows the three hits off the record—the aforementioned Zeusian proclamation, “Tragedy” (with its actual thunder sound effect), and the lighter-than-air “Too Much Heaven,” all of which hit Number One, and all of which got mad spins on my parents’ record player. They were merely the tip of the Beegeean iceberg, though. Several of the album cuts on Spirits couldashouldamighta been hits, had they ever been released on 45 RPM.

Everybody knows the three hits off the record—the aforementioned Zeusian proclamation, “Tragedy” (with its actual thunder sound effect), and the lighter-than-air “Too Much Heaven,” all of which hit Number One, and all of which got mad spins on my parents’ record player. They were merely the tip of the Beegeean iceberg, though. Several of the album cuts on Spirits couldashouldamighta been hits, had they ever been released on 45 RPM.

Right after the three singles on Side 1, came “Reaching Out,” which found Barry once again bringing forth the sensitive falsetto and tremblin’ vibrato to explain to the listener just how heartbroken he is. “Never hear a single word,” he whimpers, “Living in a lullaby / Praying every tear I cry / Living my life without you.” It’s all so very sad, one might be forgiven for not noticing the absence of the other brothers—the harmonies and choruses and small falsetto ensembles all appear to be little more than overdubbed Barrys. Nevertheless, the song is solid; not quite as striking as “Too Much Heaven,” but it works nicely, regardless of how many Barrys (or how few Robins or Maurices) are present.

“Spirits (Having Flown),” the album’s title track, is a wonderful piece of pop schizophrenia. The verses and post-chorus instrumental breaks have a very “island” flavor to them—lightly tapped percussion, bright-sounding acoustic guitar, perhaps a steel drum back there in the mix, as well. The chorus, though, is all Gibby drama—delivered in falsetto, of course—a heroic proclamation like the earlier proclamations:

I am your hurricane, your fire in the sun

How long must I live in the air?

You are my paradise, my angel on the run

How long must I wait?

It’s the dawn of the feeling that starts from the moment you’re there

“I am your hurricane! You are my paradise! How long must I wait? Woman, how long must I live in the air?” No wonder chicks swooned at this stuff, both here and on the smokin’ “Search, Find”:

Search, find

No stone unturned, no hell, no fury gonna stop my love and all its glory

Search, find

No man, no god, no pain can sever my love for you

God, we’re forever

Imagine someone saying that to you—and cold sober, at that. Who wouldn’t melt? And is that the Chicago horn section? Why, yes it is! Hot Streets was being recorded in the same studio complex, so James Pankow, Walt Parazaider, and Lee Loughnane swung by to add their distinctive flavor to the track (the Gibbs added vocals to Hot Streets‘ “Little Miss Lovin'”).

Imagine someone saying that to you—and cold sober, at that. Who wouldn’t melt? And is that the Chicago horn section? Why, yes it is! Hot Streets was being recorded in the same studio complex, so James Pankow, Walt Parazaider, and Lee Loughnane swung by to add their distinctive flavor to the track (the Gibbs added vocals to Hot Streets‘ “Little Miss Lovin'”).

My favorite of the non-singles, though, is “Living Together.” Buried deep on Side 2, the track features Robin Gibb’s only lead vocal on Spirits, and, of course, he’s singing falsetto, which was not his forte. His forte was gargling as he sang. It was a tuneful gargle, mind you (think “Massachusetts,” “I Started a Joke,” and the like), but a gargle all the same. Add the falsetto, and his throat was doing all sorts of things throats were not made to do. Meanwhile, Barry testifies on the choruses, alternating his own helium delivery with a deep, macho shout. “Why ain’t we livin’, livin’ together, instead of being so, so far apart?” he asks, going high. “Why ain’t we livin’ together, livin’ together, instead of bein’ alone?” he also asks, going low. Maurice just looked on, shrugging.

Spirits Having Flown was the first record I bought with my own money—I was nine years old at the time—and, as such, can be partly credited with beginning hobby/obsession that has cost me thousands of dollars over the years. There’s little I would change, though (with the possible exception of buying that third Men at Work album in ’84, and those three Jandek CDs when I was old enough to know better), and I return regularly to Spirits and its great pop songs. When I sing along, though, it’s in a lower register.

Comments