There are two types of people following Taylor Swift right now. The first is the type that sees her as a vacuous narcissist with too much control over pop culture, who want to see her taken down, her omnipresence muted if not halted. The other type wants to be her friend, because a friend of Swift seems to be a safer place to stand at the moment. Her fans are beyond loyal, and while being a “FoTS” won’t gain you any more relevance, it won’t subject you to hard backlash either.

There are two types of people following Taylor Swift right now. The first is the type that sees her as a vacuous narcissist with too much control over pop culture, who want to see her taken down, her omnipresence muted if not halted. The other type wants to be her friend, because a friend of Swift seems to be a safer place to stand at the moment. Her fans are beyond loyal, and while being a “FoTS” won’t gain you any more relevance, it won’t subject you to hard backlash either.

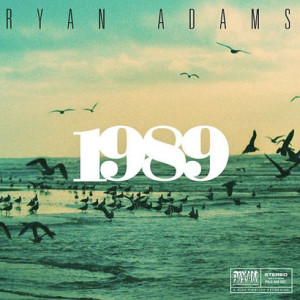

With his cover album 1989, Ryan Adams has positioned himself firmly in the latter camp, and on the whole has made the right decision. Some of these revisions are not served well by his earnest takes — not faithful in the strictest sense to the originals, but squarely respectful — but he approaches this as a project worth his effort and not as a brash and bratty vendetta. This is a crucial choice that makes the album as polarizing as Taylor Swift is herself, but we’ll explore that in a moment.

When I say that Adams’ voice doesn’t always do miraculous things with Swift’s tunes, that is a generational thing. Making her full-fledged graduation to neon-and-chrome-plated pop star, Swift sings in the parlance of the times. The words are clipped and cutting, and not very poetic. You wouldn’t write any of them out in flowing calligraphy and hang them on your wall. It’s really about getting her to the big chorus with the multitracked harmony hook, and that is part of the formula producers/collaborators Max Martin, Shellback, Jack Antonoff and others have been employing for years now. This is all of a piece and works for her on that order.

For Ryan Adams, who at the best of times has been known to be a more than competent wordsmith, the contrast is drawn sharper. Because these redone versions are couched mostly in acoustic arrangements, the skeletal frailty of the lyrics poke through readily, less like a revelation of some deep meaning within sparse language than just sparse language. It other words, when Swift performs “Bad Blood” the words and music lock together with a sense of precision, whereas Adams’ version reveal the lyrics like a string of peevish tweets. And yet, removed from the high school drama and gossippy underpinnings that sell Swift’s version more than any inherent qualities do, Adams’ version is eminently listenable and enjoyable. If you listen to it long enough, you might even be able to interpret it as a shot across the bow of ex-wife Mandy Moore and the “irreconcilable differences” cited in the divorce papers.

The whole album is easily consumed, in fact, even though one could argue that it has been transformed into “Dad Rock.” “Shake It Off” has been retrofitted into a cousin of Bruce Springsteen’s “I’m On Fire” and one can easily discern other Americana/roots rock touchstones informing Adams’ approach.

For that other side that wants to see Swift pulled down from her throne — remember that we have lived a full year under her crushing reign as pop’s most powerful being — there’s going to be many complaints that Ryan Adams hasn’t gone the full Hamlet on her. I actually read a few reviews that complained that he failed to produce the snarkalicious knife-twist he should have, which is a lot like saying he failed to produce something that works only on spite, and somehow he should be condemned for his reverence. Adams’ 1989 survives from becoming an artifact of hipster protest mockery because it is thoughtful in what it does.

It is still a stunt. The primary point of the album’s existence, particularly at this time, is to signal that Adams still exists too. Once the flush of interest has faded and everyone has moved on to the next great outrage or meme, 1989 will settle in as a novelty or curio. Even Adams’ biggest fans will have to admit in a year’s time that they’ll go back to something like Cold Roses before they time travel back to 1989. But at least if they do revisit it, it will be because of some level of musicality and not perverse parody. 1989 is a good album; a temporary thrill, not a cheap one.

Comments