People get into the fandom scene because they are deeply and sincerely interested in an artist, of course. But it’s also an effective way to boost one’s own self-esteem, because there’s always someone to look down upon and regard with suspicion. Every fan gets to set their own yardstick as to what constitutes ”good” and ”bad” fandom — and to locate themselves, inevitably, in the ”good” category. Like Baby Bear’s porridge, their fannish devotion is neither too hot nor too cool; it’s always ju-u-ust right.

People get into the fandom scene because they are deeply and sincerely interested in an artist, of course. But it’s also an effective way to boost one’s own self-esteem, because there’s always someone to look down upon and regard with suspicion. Every fan gets to set their own yardstick as to what constitutes ”good” and ”bad” fandom — and to locate themselves, inevitably, in the ”good” category. Like Baby Bear’s porridge, their fannish devotion is neither too hot nor too cool; it’s always ju-u-ust right.

As an initiated fan, you can cast confident side-eye on those noobs who haven’t even got the full studio discography, and who don’t even recognize their own favorite songs until the vocals come in. But on the other hand, if you should find yourself the object of family concern because you spend six months a year and thousands of dollars following the band around the country, and sleepless nights scouring the torrent sites for audience bootlegs of that second show in Kuala Lumpur — well, it’s not like you’re obsessed or anything. If you look hard enough, you can always find somebody who’s way more into it than you.

Someone like Bill Pagel, for instance, a pharmacist from Wisconsin who moved all the way to Hibbing, MN, with the thought of buying the old Zimmerman place — Bob Dylan’s childhood home. Pagel has been collecting Dylan artifacts for years; posters, programs, newspaper clippings, set lists, handwritten lyrics, receipts. He has boxes of documents in storage facilities all over the country. He bought baby Bob’s high chair at auction, fa chrissakes.

The old Zimmerman place might be the basis for a museum of some kind, a place for Pagel to archive and catalog his vast assortment of memorabilia. Or it might be just another trophy. In any case, the current occupants weren’t interested in selling. Pagel didn’t mind. He bought the house on the adjacent lot instead, started putting down roots in Hibbing, and settled in to wait.

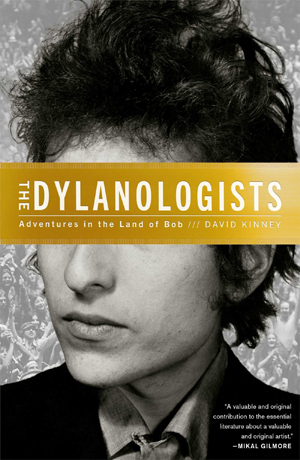

Pagel is one of the fascinating, slightly terrifying figures in David Kinney’s new book The Dylanologists: Adventures in the Land of Bob, out this month from Simon and Schuster — one of the tribe of which Kinney, a Pulitzer Prize-winning political journalist, counts himself a member, a tribe consisting, in his words, of ”We who listen too hard.” These are the folks who seek, in the music of Bob Dylan, nothing so crass as entertainment or joy, but meaning; connection, enlightenment, purpose.

Some are essentially comic characters. Kinney writes acidly of the notorious crank A.J. Weberman, who constructed an exhaustive concordance of Dylan’s songs. Convinced his hero was using his music to send coded messages, Weberman published a 500-page dictionary laying out the word-for-word substitution cipher he’d found in Dylan’s lyrics. Dylan engaged with him for a time, but when Weberman’s behavior escalated to full-on stalkerdom — hanging around Dylan’s house in New York, sifting through his garbage cans, even harassing his wife — they had a decisive break, culminating in Dylan punching Weberman’s lights out.

Some stories are more troubling; the book’s most tragic passages recount the life and death of RenÁ©e Shapiro, a Texas woman who took to calling herself ”Sara Dylan” and insisting that she was Bob’s twin sister — the fact that he was more than decade older notwithstanding. Shapiro was constant presence at Dylan shows throughout the 1980s and early 90s, bumming around the world on the graces of strangers, hitchhiking from show to show, even following the Never Ending Tour to Australia. In Kinney’s sensitive, sympathetic portrait, the picture emerges of a woman obviously mentally ill, but entirely harmless. The Dylan organization seemed to agree, and came to treat her as a sort of mascot — always reserving a ticket for her, even footing her hotel bills on occasion. But one day in 1992, RenÁ©e Shapiro hitched a ride with the wrong stranger; twenty years later, her personal effects were found in a safe-deposit box belonging to serial killer Joseph Naso.

Some stories are more troubling; the book’s most tragic passages recount the life and death of RenÁ©e Shapiro, a Texas woman who took to calling herself ”Sara Dylan” and insisting that she was Bob’s twin sister — the fact that he was more than decade older notwithstanding. Shapiro was constant presence at Dylan shows throughout the 1980s and early 90s, bumming around the world on the graces of strangers, hitchhiking from show to show, even following the Never Ending Tour to Australia. In Kinney’s sensitive, sympathetic portrait, the picture emerges of a woman obviously mentally ill, but entirely harmless. The Dylan organization seemed to agree, and came to treat her as a sort of mascot — always reserving a ticket for her, even footing her hotel bills on occasion. But one day in 1992, RenÁ©e Shapiro hitched a ride with the wrong stranger; twenty years later, her personal effects were found in a safe-deposit box belonging to serial killer Joseph Naso.

These stories, and many others with consequences less profound, all point towards the edges and limits of a certain interpretive approach. Of the tribe who ”listen too hard,” Kinney writes, ”We keep track of everything: every recording session and every tour date, every song on every bootleg… We are preoccupied with facts and dates, as if cataloging these things will solve the mysteries of his life, and ours.” Art is reduced to a cryptogram, a message in invisible ink; rather than aiming for beauty or transcendence, songs become vehicles for hidden meanings, with no more aesthetic significance than the Enigma machine or the Junior Jumble.

In The Dylanologists, David Kinney manages the difficult task of writing from within the subculture while retaining enough distance to recognize how it can go disastrously awry. Bob Dylan has, for half-a-century now, been at the center of an adulation that both invigorates and exasperates him. You cannot imagine that he is ungrateful for the love of so many strangers; but he has never been shy about admitting, with weary disdain, that many of them are simply missing the point. The Dylanologists strikes much the same tone, although perhaps more forgivingly. Even in its cataloging of the worst excesses of the Dylan fan community —the blind spots, the preoccupation with minutiae, the reductionism of the interpretive strategies, the incessant, grinding, bloody literal-mindedness — it remains affectionate to its subject.

Caveat lector: This review was prepared using a digital edition provided by the publisher.

Comments