The problem with monsters is that, when you come right down to it, they’re not that scary. Oh, zombies and kaiju and slaver-mawed xenomorphs can put you in a world of hurt; but when nightmares take flesh, they also take on the frailties to which all flesh is heir. As Arnold so eloquently said: ”If it bleeds, we can kill it” — with a shovel to the dome, with cleansing fire, with bullets, silver or otherwise. Even the precision-tooled murder machines of the Alien franchise can be blowed up real good, given sufficient firepower.

The problem with monsters is that, when you come right down to it, they’re not that scary. Oh, zombies and kaiju and slaver-mawed xenomorphs can put you in a world of hurt; but when nightmares take flesh, they also take on the frailties to which all flesh is heir. As Arnold so eloquently said: ”If it bleeds, we can kill it” — with a shovel to the dome, with cleansing fire, with bullets, silver or otherwise. Even the precision-tooled murder machines of the Alien franchise can be blowed up real good, given sufficient firepower.

Since our days huddled in the caves, we have told each other stories about the monsters lurking in the darkness, waiting to kill and devour us. It wasn’t until the 20th Century that the fiction of fear took on a new, existential cast. Howard Phillips Lovecraft (1890 — 1947) didn’t invent cosmic horror; but in a slew of short stories and novellas, and by his mentorship of a circle of like-minded writers, he staked out ownership of the genre so thoroughly that it will ever after be called ”Lovecraftian.”

Lovecraft bridged the worlds of horror and science fiction, and his themes were foretold in the marvelous opening paragraph of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds:

No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s… that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinised and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency men went to and fro over this globe about their little affairs, serene in their assurance of their empire over matter. It is possible that the infusoria under the microscope do the same. No one gave a thought to the older worlds of space as sources of human danger…. Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us.

There are things out there, in other words, somewhere in the Outer Dark, beyond the reality of our senses — things that can harm us. But H.P. Lovecraft’s ”intelligences,” unlike Wells’ Martians, will not deign to envy Man, or even to notice him. They operate on scales of space and time that beggar description. If they regard us at all, it is as vermin. Their malice is as impersonal as it is all-encompassing. The destruction of human beings is merely a side effect of their presence. In the face of these cosmic monstrosities, all human endeavor is meaningless; our dignity and self-importance are but vanity and folly. We are no more than debris, caught up in the gravity of these titanic pan-dimensional entities. This was Lovecraft’s great innovation — reinventing horror as an expression of post-World War existential despair, fuelling it with weaponized nihilism.

Many a genre writer has cranked out a Lovecraft pastiche, for the superficial aspects of his style — the tentacles, the forbidden lore, the signature archaic adjectives (eldritch, cyclopean, tenebrous and the like) — are easy enough to imitate. Precious few of them, though, show any true feeling for the modernist neuroses that gave the original stories their creepy tingle.

Into this arena steps the new anthology Lovecraft’s Monsters (Tachyon), edited by Ellen Datlow and featuring a hit parade of contemporary fantasy and horror writers. Datlow, to her credit, sets out to avoid outright pastiche in her selections. But there’s something about the Cthulhu mythos that seems to inspire writers to play dress-up; and so many of the selections put Lovecraft’s creations through various genre exercises.

Sometimes these experiments yield terrific results. Laird Barron’s ”Bulldozer” is bloody good fun, bringing the Elder Gods to the Wild West in an earthy, violent tale that starts like an episode of Deadwood gone terribly wrong and builds to a skin-freezing climax. ”The Bleeding Shadow,” by Joe R. Lansdale, is another highlight, translating the setup to Lovecraft’s own ”The Music of Erich Zann” into the world of Texas blues. Lansdale employs a hard-boiled narrative voice (consciously?) reminiscent of Walter Mosley. (Lansdale’s use of African-American protagonists would surely horrify the virulently-racist Lovecraft, which is all the more reason to admire it.)

Howard Waldrop and Steven Utley, writing in tandem, start their ”Black as the Pit, from Pole to Pole” at the point where Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein leaves off, taking the forsaken creature on a magical mystery tour of a hollow Earth, an odyssey that touches on works by Poe, Jules Verne, and Edgar Rice Burroughs. The clever conceit and sharp writing make this one a pleasure on a par with the popcult madness of Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen comics.

Other exercises are less successful. Nadia Bulkin’s ”Red Goat Black Goat” has a unique Indonesian setting, but its horror is more Amityville than Dunwich; and Kim Newman’s ”A Quarter to Three” is scarcely a story at all, amounting to an extended ”man walks into a bar” joke.

Elsewhere, star writers deliver in accordance with the expectations of their personal brands; that’s good for editors, of course — big names sell books — but here my biases cannot help but come into play, especially when the work seems chosen less for its fresh take on the subject than for the author’s marquee value. Some of the biggest disappointments in Lovecraft’s Monsters come from the biggest names.

Neil Gaiman has been to the Lovecraft well before — for attempted comedic effect with ”I, Cthulhu,” and rather more successfully with ”A Study In Emerald,” which sets the mythos in the world of Sherlock Holmes. (What did I say about Lovecraftians and their penchant for dress-up?) ”Only the End of the World Again” shoehorns the werewolf protagonist of Lon Chaney’s Wolf Man movies into the environs of Innsmouth. There’s probably a compelling story to be written contrasting classic monster-movie tropes with Lovecraft’s more esoteric approach, but this ain’t the one.

Further in, CaitlÁn R. Kiernan does the CaitlÁn R. Kiernan thing with ”Love Is Forbidden, We Croak and Howl,” dealing up the usual pervy cocktail of romance n’ death among monstrous outsiders — the stuff you came for, if you’re already a fan, but unlikely to convert you if you’re not. Thomas Ligotti trades on his reputation as a ”writer’s writer,” by which is apparently meant that he produces elegant prose in which nothing actually happens; his contribution, ”The Sect of the Idiot,” has all the visceral terror of a policy paper. The late Karl Edward Wagner, though, is well-represented by ”I’ve Come to Talk With You Again” — a slight but perfectly-observed vignette about writers, fandom, and the Faustian bargains of fame.

Further in, CaitlÁn R. Kiernan does the CaitlÁn R. Kiernan thing with ”Love Is Forbidden, We Croak and Howl,” dealing up the usual pervy cocktail of romance n’ death among monstrous outsiders — the stuff you came for, if you’re already a fan, but unlikely to convert you if you’re not. Thomas Ligotti trades on his reputation as a ”writer’s writer,” by which is apparently meant that he produces elegant prose in which nothing actually happens; his contribution, ”The Sect of the Idiot,” has all the visceral terror of a policy paper. The late Karl Edward Wagner, though, is well-represented by ”I’ve Come to Talk With You Again” — a slight but perfectly-observed vignette about writers, fandom, and the Faustian bargains of fame.

With its emphasis on the eldritch and the alien, the cosmic horror genre can feel cold, even clinical — but Lovecraft’s Monsters is at its best when its stories find an emotional center. Brian Hodge’s novella ”The Same Deep Waters as You” stands as a cautionary tale about the limits of empathy, as a psychic ”animal whisperer” is recruited by military intelligence to attempt communications with a captive cohort of Deep Ones — the amphibious, semi-human slaves of Cthulhu. Elizabeth Bear’s ”Inelastic Collisions” takes us directly into the heads of extradimensional predators trapped in human form, and finds sympathy even for these devils. ”Waiting at the Cross Roads Motel,” by Steve Rasnic Tem, finds the blighted offspring of humans and Elder Gods converging to herald the return of their long-absent fathers; it’s a little masterpiece, dense with metaphorical potentialities for abandonment, psychopathy, the cycle of abuse, congenital mental illness — all the woes we inherit from our elders.

The longest of the bunch, and perhaps the best, is Fred Chappell’s ”Remnants.” The novella is set after the return of the Elder Gods. The Earth is in ruins; the native flora and fauna, including the human species, are headed for extinction as the planet’s new rulers transform the environment to suit themselves. A broken family wanders a postapocalyptic southeast, their hopeless perseverance calling to mind Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Chappell methodically grounds the story in psychological realism, even as he introduces elements of space opera. He doesn’t quite stick the landing — the narrative seems to break off in mid-sentence — but it’s a haunting story, and exquisitely written.

Most importantly, it keeps the monsters at arm’s length. We see the evidence of their passing in ”Remnants,” hear the shrill cries of Tekeli-li in the distance; but the influence of the ”Olders” and their servants is felt mostly in images, feelings, dreams. Lovecraft’s most fearsome creations come from a realm of ideas — derangements and infections that irrupt into our universe, as subtly unsettling as a bad smell from a source unknown.

Most importantly, it keeps the monsters at arm’s length. We see the evidence of their passing in ”Remnants,” hear the shrill cries of Tekeli-li in the distance; but the influence of the ”Olders” and their servants is felt mostly in images, feelings, dreams. Lovecraft’s most fearsome creations come from a realm of ideas — derangements and infections that irrupt into our universe, as subtly unsettling as a bad smell from a source unknown.

The physical manifestation of these horrors robs them of their mystery and power. Once you distill evil into a form that can be rendered with a rubber suit or CGI polygons, you’ve got something you can wrap your head around — something that can be fought, even killed. And the monsters in Lovecraft’s original stories can, on occasion, be killed — by fire, by lightning, by magic powders. The hell-spawn in ”The Dunwich Horror” is mauled to death by a dog, for cry-eye, and dogs aren’t even that tough. Even dread Cthulhu is a thing of flesh and blood — or ichor, or protoplasm, or whatever. If you had a big enough bomb, you could hurt the bastard.

But you can’t fight a nasty thought. Once it latches on inside your head, you’ll never destroy it; the only escape is to destroy yourself.

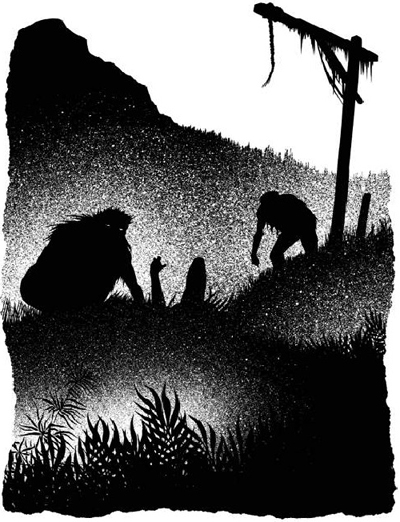

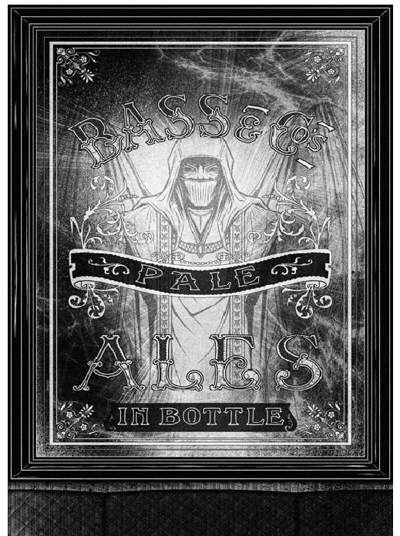

This, perhaps, is why Lovecraft’s work has not fared particularly well on film. His is a uniquely literary conception of horror. It’s not just that forbidden books feature so prominently in his stories — it’s that books are vehicles for ideas. Their physical forms are ultimately less important than their memetic payload. (That said, Lovecraft’s Monsters is beautifully designed, and John Coulthart’s illustrations, all scratchy lines and tenebrous shading, are magnificently vile.)

In the same way, Cthulhu is not scary because he’s a fifty-story humanoid with bat wings and a squid for a face. He is scary because he was, in ages past, taken for a god, and worshipped with unspeakable rites; and to even speak his name aloud is certain doom, for his loathsome presence will haunt your dreams and disorder your senses, driving you inexorably towards madness. He will get inside your head, like a story — not a story that enlightens, but one that corrupts and destabilizes. He is a disturbing idea; and ideas are the most terrifying monsters of all.

Caveat lector: This review was prepared using a digital edition provided by the publisher.

Comments