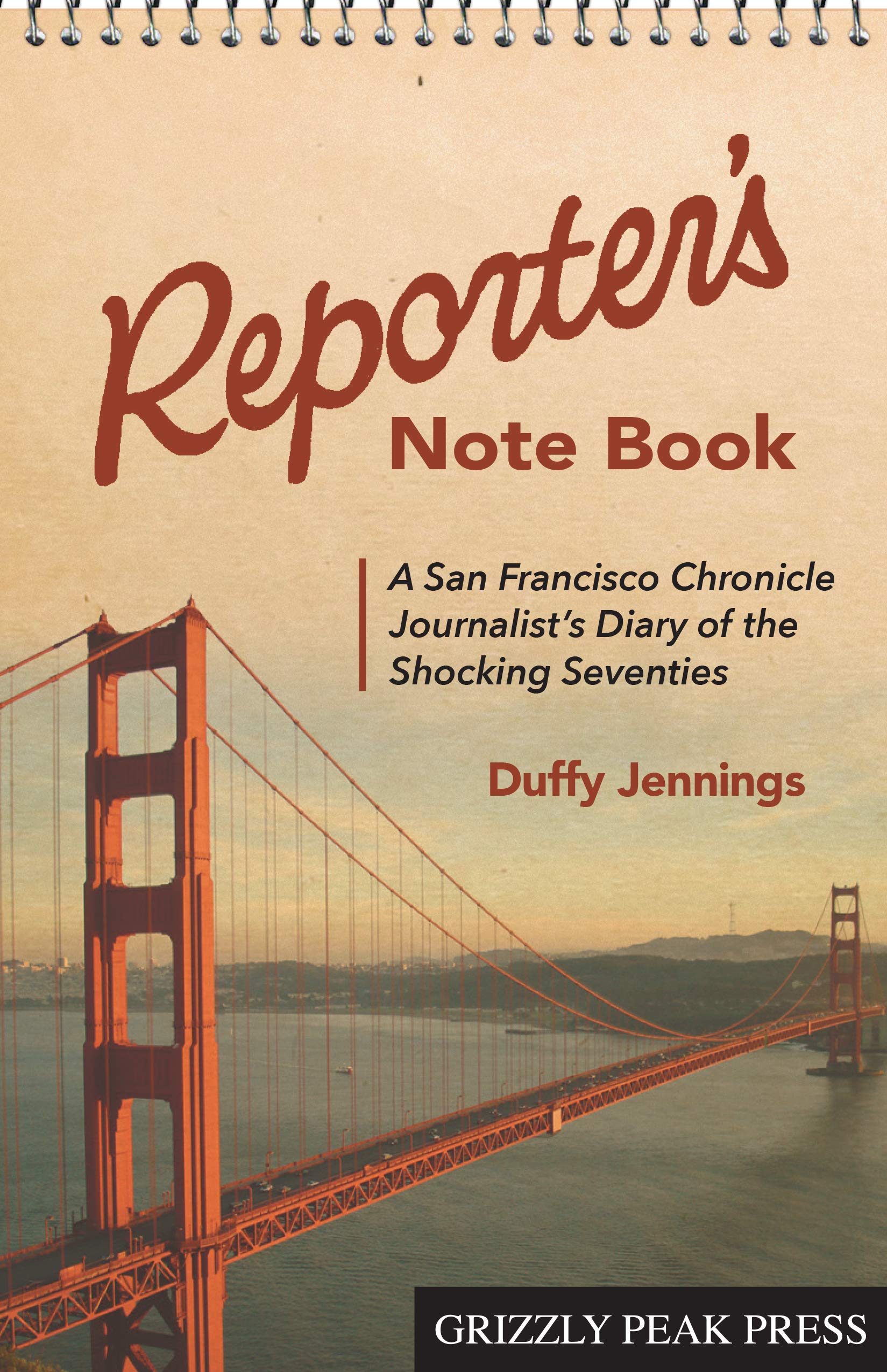

Duffy Jennings — Reporter’s Note Book: A San Francisco Chronicle Journalist’s Diary of the Shocking Seventies (2019, Grizzly Peak Press, $17.95 U.S.) Purchase this book (Amazon)

There’s an old derogatory phrase about California which states that it’s a land of fruits and nuts. Throughout its history, The Golden State often drew social outliers to the West Coast. These folks would come from cultures and communities where their behavior and ways of being in the world could be considered deviant by those they lived with. Not always deviant in the pejorative sense, but rather in the sociological sense where some people deviate or depart from what’s considered the norm or normal in that community. San Francisco in particular has been a place where many social outliers tend to congregate. During the 60s and 70s, The City went through a period when the best and the worst of nonconformist expressions and actions seemed to flourish. One person who covered some of the biggest news stories about some of these outliers was Duffy Jennings, a reporter for The San Francisco Chronicle. From the Zodiac killings, to Patty Hearst, to the murders of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk, to dance fads and new dating rituals, Jennings had a fairly substantial career as a reporter in San Francisco. However, in his book, he also weaves in a number of tales about another turbulent time: growing up with alcoholic family members while sometimes struggling with the hard drinking culture in the newspaper industry and multiple marriages.

While memoirs by journalists are not uncommon, Jennings’s story is interesting in that he’s focusing on a newspaper career characterized by an upward trajectory that takes him from being a copyboy to a reporter in a short period of time. Indeed, if it weren’t for the fact that both his parents worked for the Chronicle as writers (his mother was more like an assistant editor to his father’s work), he might not have had the opportunity to go from such an entry-level position to being a full-time reporter. The old adage of who you know certainly applies to Jennings’s journalism career, and his post-newspaper career as a publicist with The San Francisco Giants. Nowadays, such a career track seems highly improbable for most folks. But back in the late 60s, even a middling-level slice of nepotism could open doors to opportunities that others struggle for years and even decades to achieve. To put a fine point on it, Jennings even has a picture of himself with the other copyboys in The Chronicle’s newsroom from 1968. In the caption it reads, ”Duffy (standing, left) with the other copyboys who were sons of Chronicle employees.” Who placed that call to get him an interview at the paper? Well, it certainly wasn’t his father Dean, whose career as a writer was very successful, but whose role as a father wasn’t. Rather it was his mother, Dori. Dori worked as Dean’s assistant when they were married. However, by the time Duffy Jennings started at The Chronicle in 1968, Dean and Dori had been divorced for years –and both had left the paper to work elsewhere. Indeed, it is Dori’s life that could easily be the subject of a film since she was the owner of a gay bar in San Francisco, suffered from alcoholism, failed relationships, suicide attempts, and was absent most of the time during his childhood and teen years. She’s a very tragic figure, and a source of great frustration for Jennings. In recounting his mother’s life, he’s certainly impressed by Dori’s intellect, her education, her business acumen, and even the way she insisted he and his brother learn proper grammar and spelling (which helped them a lot during their early adult years). However, like his relationship with his father, the emotional walls built up by years of neglect separated them in ways that paved the way for many personal issues that would manifest themselves later in Jennings’s life. As it should be abundantly clear by now, Reporter’s Note Book is a professional and personal recollection that examines the tumult of the 1970s through both lenses.

We currently live in a time where it seems there’s a crisis every day. However, when looking at the chaos and crises that befell San Francisco in the 60s and 70s, it makes some of what passes for Breaking News today look kind of small. Take the terror that the Zodiac killer inflicted on the Bay Area between 1968 and the 1970s. Brutal slayings in Vallejo, Lake Berryessa, and in San Francisco came with taunting and threatening letters sent to The Chronicle — which they published to inform the public, but had the consequence of inflating the ego of the killer and frightening the crap out of many people as well. Then, there was the kidnapping of Patty Hearst from Berkeley by the so-called Symbionese Liberation Army — which was shocking enough. But when you add that she was brainwashed into working with them to rob a bank in San Francisco in 1974, I’m sure more than a few Bay Area folks were asking, ”What the hell is going on with this world?” Fold in the panic generated from multiple random shootings in The City known as the Zebra murders, and then add the proverbial cherry on top: San Francisco Supervisor Dan White shooting and killing the Mayor of the city and the first openly gay Supervisor at City Hall in 1978. Imagine how all this would play on Twitter and cable news if this were happening now? Using the superlative that the 1970s were ”shocking” was not overstating what was happening the Bay Area during that decade. However, it wasn’t all doom, gloom, and death. Jennings does spotlight the heroism and the all-too-humanism of firefighters in San Francisco, listening to Smokey Robinson sing in a hotel room shower before an interview with the singer, highlighting cultural fads like disco dancing and singles bars, and even penning a ”What Ever Happened To…” of his graduating high school class from 1965. In short, Jennings was doing what other newspaper writers do: giving us the first draft of history from that era. It’s not exactly a pretty picture of the 70s — but sometimes life isn’t pretty.

Reporter’s Note Book is written in a compact and direct manner — which is befitting a journalist from that era. He gets to the point in chapter after chapter, with prose that’s lean, unadorned, but often packing a wallop. Indeed, one of the things I both appreciated and found a bit frustrating was how short the chapters were. However, given the fact that Jennings cut his teeth in a newsroom, writing relatively short, digestible pieces is in his DNA. The chapters on his family history have an honesty that pull very few (if any) punches when it comes to his mother and father, but he’s more vague when writing about his marriages, his children, and brother. Perhaps going into detail on those things was too much of an emotional minefield, but this book isn’t about self-therapy or examining an unexamined soul. Rather, Reporter’s Note Book is Jennings’s first draft of Bay Area history where the personal, the political, and the social aspects of that era often intersected in powerful and dramatic ways.

Comments