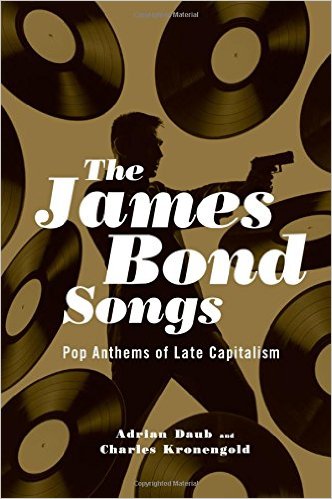

Adrian Daub and Charles Kronengold— The James Bond Song: Pop Anthems of Late Capitalism (2015, Oxford University Press, $29.95 U.S.) Purchase this book (Amazon)

Adrian Daub and Charles Kronengold— The James Bond Song: Pop Anthems of Late Capitalism (2015, Oxford University Press, $29.95 U.S.) Purchase this book (Amazon)

When it comes to theme songs for James Bond movies, your mind may harken back to Shirley Bassey. For better or worse, Shirley Bassey set the standard for ”Bond songs”– and many performers who came after her often took the mic to deliver over the top performances that fell squarely into stylistic trappings of composer John Barry. And even if you don’t know who Shirley Bassey is, you can just listen to Adele sing ”Skyfall” to know what I’m talking about.

Except for Paul McCartney’s ”Live and Let Die” and Carly Simon’s ”Nobody Does It Better,” most of the Bond theme songs are forgettable — at least according to Adrian Daub and Charles Kronengold in The James Bond Songs: Pop Anthems of Late Capitalism. And looking over the list of songs in their wonderfully cheeky book, it’s pretty clear that they are mostly correct. For me, though, ”For Your Eyes Only” by Sheena Easton and ”A View To a Kill” by Duran Duran should be added to the list of memorable Bond songs — with ”You Only Live Twice” sung by Nancy Sinatra and Dusty Springfield’s ”The Look of Love” coming in on the b-list. But that’s a quibble perhaps owing to Gen X’ers (like me) who seemed a-ok with Easton’s adult contemporary ballad in 1981 and was really a-ok with Duran Duran (who had a number one hit with their Bond song in 1985). However, chart positions aren’t completely indicative of what makes for a memorable Bond song because many have done very well on the charts, but they haven’t remained fixtures on the airwaves (or in pop culture) since their release — except for Paul McCartney. That’s part of the conundrum of what Daub and Kronengold mine throughout their book. They are very aware — and make a compelling case — of how forgettable these songs are, but they also reveal how Bond’s presence in these films mark stages of late capitalism that span 50 years of time between colonialism, the Cold War, and the post-9/11 political culture.

While Daub and Kronengold do examine the plot of the films, their primary focus is on the songs and the title sequences that are often stand alone montages revealing to viewers what’s going on in Bond’s mind. For the most part Bond is thinking about women, sex, and guns. But even that gets complicated as the author’s take us through the decades to see how Bond goes from ”Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang” to a man who has a lot of anxiety at what the post-colonial and post-Cold War world has wrought. That tension was expressed in the ham-handed ways Bond responded to the changing sexual mores — and his growing feeling of inadequacy as the series progressed. As Daub and Kronengold explain, Bond’s psychological anxieties stem from his anachronistic and conservative personality that often put him behind the times: ”His time is the immediate present, with the latest technological advances; but his time is also a recent, already mythic past, when people depended on the United Kingdom for world peace, when colonialism had some legitimacy left, and when whiteness wasn’t ”white” but simply ”universal.”

The universalism of Cold War politics frame the Bond narratives through the 80s, but by the 90s, Bond’s sexual unease morphed into the gay panic years in films like ”The World is Not Enough” where Bond and Renard have a kind of homosocial triangle with Elektra King in the middle. By the 2000s, Bond was being repackaged as ”new” — even though Bond was essentially doing the same kind of things he’s been doing since the 1960s. However, it’s Madonna’s ”Die Another Day” opening sequence where we get to what Bond fears the most. The long torture sequences with images of drowning, scorpions, and other brutality inflicted on Bond intersect with ”what Freud would call the film’s ”primal scene.” The rest of the film work through the repercussions of what happens while the song plays. And what happens is that former colonial subjects, women, and communists finally get their hands on Bond.” In other words, the white man of power and privilege — who is to be universally revered — is now violently kicked off his perch by those his universal privilege subjugated. Yeah, all that is expressed in an opening montage — according to the authors.

Regarding the authors: Daub and Kronengold are clearly academics who bring a deep reading to pop culture, but they are also funny at times. For example, they ask about the main character in the song ”Surrender” by k.d. Lange (the one who says ”I am in control”): ”Who are you, if you begin a first-person utterance with the phrase, ”The news is?” A complete dick, that’s who.” Is that dickishness a feature of ”late capitalism?” It’s certainly possible, but Daub and Kronengold overlook that specific personality trait and defer to those who are more well versed in what late capitalism is (i.e., Economist Joan Robinson and political theorists Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri). What they settle on is that late capitalism ”has no purpose except to keep the show going.” Since we as workers in late capitalist countries no longer make things, and we no longer have communists to fight (even though ISIS and Iran are supposed to be their replacement), the primary job of capitalism is to keep asserting its superiority to anything else. James Bond represents that superiority in a changing world, and his presence (just like the songs) are designed to ”assert a commonness” in a fragmented pop culture. And it’s those fragmented montages at the beginning of a Bond film that represent the late capitalist dreams of 007. His presence on the big screen every few years keeps the show going — a show that’s been repeating itself with minor variations for over 50 years.

Comments