Being a meditation on the occasion of Alan Light’s new book, The Holy or the Broken …

Even Leonard Cohen is getting sick of ”Hallelujah.” A few years ago, after his iconic ballad showed up on the soundtrack for the dumb, superficial Hollywood adaptation of Watchmen, underscoring a protracted sex scene that left audiences groaning, Cohen jokingly suggested that perhaps it was time to declare a moratorium on the use of the song for film and TV. That’s a bold statement, given that ”Hallelujah” literally puts money in Leonard Cohen’s pocket every time it is performed, by him or by anyone else.

Even Leonard Cohen is getting sick of ”Hallelujah.” A few years ago, after his iconic ballad showed up on the soundtrack for the dumb, superficial Hollywood adaptation of Watchmen, underscoring a protracted sex scene that left audiences groaning, Cohen jokingly suggested that perhaps it was time to declare a moratorium on the use of the song for film and TV. That’s a bold statement, given that ”Hallelujah” literally puts money in Leonard Cohen’s pocket every time it is performed, by him or by anyone else.

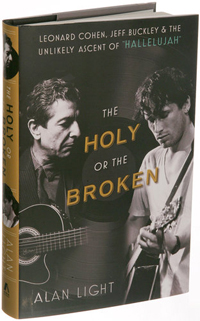

Strange fate, that such a song — a one-word refrain wrapped around a changeable array of verses that meander from Biblical allusion to kinky sexual imagery at a whim — should achieve the currency that ”Hallelujah” has; as a go-to karaoke track, a standby soundtrack choice for film and TV, a vocal showcase for X-Factor contenders. Now Alan Light has written The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and the Unlikely Ascent of ”Hallelujah,” a new full-length book charting the song’s rise from an album track on an independently-released record to its current ubiquity.

There aren’t many single songs that have sufficient cultural impact to merit an entire book. I’ll give you ”Strange Fruit,” for sure, and maybe ”Gloomy Sunday.” (And I must disclose here that I have not read Light’s book in its entirety; no review copy was available to me at the time of this writing.) But much has been written about ”Hallelujah” since its release, by fans and musicians and even by academics, and I know the song, in its various versions, quite well; like every other white boy with a guitar, I’ve even performed it a few times. And the story that’s often missed, when the story of ”Hallelujah” is told, is of the radical shifts in meaning that the song has undergone in its ”unlikely ascent.”

To begin with the obvious — or perhaps not-so-obvious — the most familiar version of ”Hallelujah” belongs to Jeff Buckley; which is to say it belongs to John Cale. As originally written by Cohen, ”Hallelujah” was a song with no set form. It was shifting, modular beast, an assortment of dozens of verses — perhaps as many as eighty, depending on who’s telling the story — all variations on a theme, which could be recombined to form infinite versions. Cohen’s original 1984 recording used four of those verses, but the songwriter himself never considered it definitive. As the song cropped up in Cohen’s live sets, its numerous iterations varied wildly in length and content.

Welsh singer-songwriter John Cale, a founding member of the infamous Velvet Underground, was the first to record a cover of ”Hallelujah,” for a 1991 Cohen tribute album called I’m Your Fan. Cale’s version used a stark piano-and-strings arrangement — very unlike the synthpop grandiosity of Cohen’s original — and a selection of five verses from the pages of notes that Cohen had supplied.

I’m Your Fan was a niche product — cult artists covering a cult artist — and Cale’s ”Hallelujah” didn’t get a lot of traction with the general public. It was Jeff Buckley’s cover, recorded in 1994, that finally ”broke” the song. Buckley hewed closely to Cale’s version, and most subsequent versions — by k.d. lang, Rufus Wainwright, American Idol’s Jason Castro, The X-Factor’s Alexandra Burke, even (God save us) Jon Bon Jovi — have hewn closely to Buckley’s.

But Cale’s contribution ran deeper than simply nailing down a definitive lyric; he redefined the song emotionally by tailoring it to his strengths as a vocalist. Cohen originally sang ”Hallelujah,” as he sings most everything, with tones of cryptic amusement. Even as a younger man, he gave the impression of having seen it all, and he’s of an age now (and was, even in 1984) to view even heartbreak as a private joke. Cale, in his rendition, gave ”Hallelujah” an aura of bruised dignity that suited his diction, his posture, the prim triplets of his piano.

Jeff Buckley’s performance, though, was all bruise, from top to toe, and became an anthem for Sensitive Guys everywhere. The studio recording literally begins with a long, shuddering sigh, and Buckley seems throughout to be on the verge of a collapse — of a swoon, really — overcome by his own deep, throbbing emotions.

There’s no intrinsic reason why ”Hallelujah” should be a cue for broody posturing. As culture scholar Michael Barthel points out, in a paper presented at the EMP Museum’s 2007 Pop Conference, ”Hallelujah” is a pretty funny song at heart, with wry asides (”You don’t really care for music, do ya?”), meta-humor (a lyric describing the chord changes as they occur), and purposely overblown imagery conflating the fleshly and the holy. There are many possible meanings for ”Hallelujah,” he argues; there’s no reason, for instance, that it couldn’t be read — or performed — as a giddy pop tune about the euphoria of new love.

It’s probably too late to reclaim the various meanings of ”Hallelujah.” Leaving aside the massive exposure of his version, the song’s association with Jeff Buckley, the man, has lent it an added weight; his personal tragedy bleeds over into the song, and it becomes impossible to read ”Hallelujah” as other than the Last Emotional Testament of a Beautiful Young Genius Taken From Us Too Soon. But in so doing, we do Leonard Cohen — and the song, and ourselves — a disservice. By leaving ”Hallelujah” open-ended, by refusing to pin down in a definitive way the content and meaning of the song, Cohen created something that could have belonged to all of us, every singer, every listener, to make of ”Hallelujah” what we will. A fixed ”Hallelujah,” with a predetermined emotional affect, is an object we can admire from afar, but not inhabit ourselves — until the next radical reimagining comes along, and some new artist, perhaps as yet unborn, finds revelations anew within the familiar rhymes.

They’ll take the song you thought you’d heard, the one you knew in every word, and crack the book and show blank pages to ya.

Comments