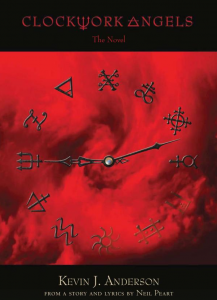

Kevin J. Anderson – Clockwork Angels: The Novel (2012, ECW Press, $24.95 U.S./$26.95 Canada)

Purchase this book (Amazon)

If Neil Peart didn’t drop out of high school to follow his bliss as a musician, he could have easily lived a life of the mind as a college professor or travel writer. Anyone who has followed the band Rush, knows that he’s been the primary lyricist behind the group’s output. And as the lyricist he gets to set the theme or concept each album explores. After Rush’s last long-form album (Hemispheres), the band took the concept album idea and shelved it for over 30 years.

With the release of the album Clockwork Angels in June of 2012, the band announced the concept album would be accompanied by a novel, written by noted science fiction author, Kevin J. Anderson. My initial reaction was ”Well, that’s a first for a band. A novel based on the record’s concept.” Then a thought-bubble with the image of Claudio Sanchez from Coheed and Cambria popped up over my head. Yes, Coheed and Cambria’s musical project has been accompanied with a graphic novel that directly relates to each album’s release. Rush and Kevin Anderson, it seemed, were doing something similar. And so it is with the novel, Clockwork Angels — a story set in a steampunk world where archetypes of order and chaos battle on a macro and micro level and centered on the life journey of the novel’s protagonist, Owen Hardy.

Owen lives in the country of Albion and dwells in the rural town of Barrel Arbor. His vocation: assistant manager of an apple orchard with his father — who is the manager. He lives an unremarkable life, has a girlfriend, a caring father, a comfortable home, a safe town where everyone knows him, and a job for life. For all intents and purposes, he should be happy that his life course is so well planned. He really lacks for nothing — except adventure and autonomy.

You see, the world of Albion functions with clockwork precision, is governed by an all-powerful Watchmaker who has ordered the world in such a way that even a rain storm can be predicted to the minute. Because it’s a steampunk world that Owen lives in, the technology is quite different from ours. Fire (and it’s a ”coldfire”) is the primary source of illumination when the sun isn’t shining, and is the only source of energy that propels the large-scale modes of transportation of steam liners, ships, and airships. Moreover, the technological innovations (from large to small) are built on a platform of clock gears (what would you expect from a world ruled by an individual called The Watchmaker)?

Within this tightly-wound world, one would expect a certain level of disorder to push back against all that order. And it does in The Watchmaker’s nemesis, The Anarchist. In the middle is Owen, who sets off from his village of Barrel Arbor the night before his birthday (a birthday when he becomes an adult) and, with a little help from The Anarchist, hops aboard one of the steam liners bound for the capital city. Owen’s only desire is to see Crown City and the famed Clockwork Angels — automatons who perform a semi-religious ritual only open to a selected group of citizens. Owen’s presence in Crown City (a naive kid with very little money and no real plans besides traveling and seeing the sights) is an anomaly. He quickly spends most of his money, cannot see the Clockwork Angels, and is eventually deported from the city and left to fend for himself. From that point, Owen is on his own and, throughout the story, faces disappointment, misfortune, heartbreak, and physical harm as he ventures from living and working in a traveling carnival, to homeless street urchin, to seeker of a lost ”Seventh City of Gold,” to almost dying at the hands of pirates. Each phase of his life seemingly gets worse as it progresses, but through it all, Owen claims he would not change a thing. Rather, through an eventual battle between the forces of The Watchmaker and The Anarchist, Owens realize where personal happiness lies, and understands that his (mis)adventures are important character building events that shape his world-view.

The story echoes themes explored on Rush’s Hemispheres album. In that narrative, Peart had logic (Apollo) and passion (Dionysus) tearing the world (and the gods) apart, and an individual who travels through a black hole to Olympus where he becomes a ”disembodied spirit” and implores the gods to stop their battles because of what it was doing to humans on Earth. In the end, the individual becomes the ”God of Balance.” Similar themes are addressed in Clockwork Angels — albeit with more subtlety and maturity. However, what the story achieves on a thematic level is lacking in character development — specifically in the main character. Because Anderson and Peart are dealing with archetypes, they draw their characters either too starkly (and thus, too stereotypically) or, in the case of Owen, without depth. Many of the secondary characters in the story are more fully drawn, and that just increases how flat Owen is in the story. Also, the hero’s journey that the protagonist goes through is one that is, for Rush fans who already know the narrative from the album, without many surprises. And perhaps that’s the unfortunate plight of hardcore fans such as myself. Reading Peart’s lyrics, grooving to Lee and Lifeson’s music, and listening to the album repeatedly created a unique narrative in my mind. Reading Anderson’s version of the story was bound to be somewhat of a letdown, but I tried to keep my love of the band at bay and focus on the merits and shortcomings of the novel. And what I found was in addition to my issues with Owen’s character, that some of the dialogue was awkward. Granted, the world in which this story is set is not ours, but the way in which the characters speak to Owen by always calling him ”Owenhardy” started to grate on my nerves. The action of the story was also plodding at times (especially in the first half of the novel), and the moment of heartbreak for Owen wasn’t something that would set most people running away with a deep emotional wound, so it was difficult for me to buy that this event was the one that set him further along the path of misfortune.

Moreover, though Anderson is a accomplished writer, there’s something distant in his prose. He’s able to paint vivid pictures of Albion with his words, but rarely is he able create an emotional connection to the people and place for this reader. Owen’s travels from place to place certainly offers the author the opportunity to introduce the reader to the different parts of Albion, but at bottom there has to be a compelling enough plot to warrant all the journeys Owen embarks on. Yes, Owen does have many adventures and misadventures (mostly misadventures), but throughout he longs for stability and the kind of rootedness he had in Barrel Arbor. Perhaps one of the morals of the story is that one cannot truly know the road to personal happiness unless one experiences rootlessness and personal misery. It seems a bit extreme, but, like I wrote earlier, considering that Anderson and Peart are dealing in archetypes, the lack of subtlety will be prevalent in a story that often times makes its point much like Friedrich Nietzsche did in his writings: philosophizing with a hammer.

(And for fans of the band Rush, Anderson has done a nice job of weaving lyrics from Rush’s catalogue into the story. Indeed, Neil Peart — who wrote the Afterward for the book — thinks there should be a contest to see how many lyrics one can find in the novel. Rush fan-boys and girls, get started!)

Comments