It’s no secret — at least not anymore — that the comic book industry was not a glamorous lifestyle in its earliest years. Writers and artists were piecemeal employees paid to get the job done, not to be “creators.” This was a double-edged sword. For those who loved the comics medium, having that job was the dream of a lifetime, but it also meant that you as a creative individual had to dial back how much effort you gave, or else you’d come up with something enduring and far-reaching and have no control or ownership of it. I don’t think that knowledge would have stopped Jack Kirby or Steve Ditko, or even Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster, even though it would have prepared them for many, many years of disrespect and financial hardship to come.

What does any of this have to do with Super Cool, the green-skinned superhero from 1974 that fronts today’s story? Not much, other than to say this was not a traditional comic book, and the writer/artist behind it was by no means a traditional creator. But to get to this point we have to go back to the 1960s.

Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor-Smith had good fortune come their way with their loose adaptation of Robert E. Howard’s iconic sword-and-sorcery character Conan The Barbarian. They have taken quite a few liberties, including the crossover introduction of Michael Moorcock’s Elric of Melnibone into Conan’s savage world. Artists come and go on so many different books. If you get a hot artist, you spread him or her around and try to capitalize on their talents and growing fan base, and hopefully, cross-pollinate around the entire publishing line. And because they’re paid like employees and not creators, they haven’t got much in their arsenal to fight with. Windsor-Smith thought, “Hell with this, I can take off on my own and keep my work.” Thomas stayed on.

In around this time he decided to pull characters from other of Howard’s stories, the strangest being Red Sonya of Rogatino. In her initial incarnation, she was a gunslinger in the 16th century, tough as nails and seeking revenge against the lusting, brutal, and bloodthirsty sultans. She did not wear a chainmail bikini. Thomas made the decision to retrofit the character into Conan’s Hyborean Age. While I don’t have the documentation to verify this, I imagine that our modern vision of the character of the rechristened Red Sonja is primarily due to the artist that was handling Conan around this time: Frank Thorne. He is so intrinsic to the Red Sonja identity that in the 1970s and possibly into the 1980s he held Red Sonja lookalike contests. He dressed up as “The Wizard” and was, to my knowledge, the main judge of the cosplay contest.

In around this time he decided to pull characters from other of Howard’s stories, the strangest being Red Sonya of Rogatino. In her initial incarnation, she was a gunslinger in the 16th century, tough as nails and seeking revenge against the lusting, brutal, and bloodthirsty sultans. She did not wear a chainmail bikini. Thomas made the decision to retrofit the character into Conan’s Hyborean Age. While I don’t have the documentation to verify this, I imagine that our modern vision of the character of the rechristened Red Sonja is primarily due to the artist that was handling Conan around this time: Frank Thorne. He is so intrinsic to the Red Sonja identity that in the 1970s and possibly into the 1980s he held Red Sonja lookalike contests. He dressed up as “The Wizard” and was, to my knowledge, the main judge of the cosplay contest.

After his run, Thorne became the author of several semi-scandalous series for mens’ magazines like Playboy and Hustler, and for magazines that catered to a “mature” audience like Heavy Metal and Warren’s 1984. Sex was generally the theme, and nowhere was that more evident than in his long-running series Ghita of Alizarr. Ghita was, in many cases, Red Sonja if Sonja liberally used sex as a weapon. I’m not passing judgment here, but I am trying to illustrate the contradictory nature between the two examples.

After his run, Thorne became the author of several semi-scandalous series for mens’ magazines like Playboy and Hustler, and for magazines that catered to a “mature” audience like Heavy Metal and Warren’s 1984. Sex was generally the theme, and nowhere was that more evident than in his long-running series Ghita of Alizarr. Ghita was, in many cases, Red Sonja if Sonja liberally used sex as a weapon. I’m not passing judgment here, but I am trying to illustrate the contradictory nature between the two examples.

With all of this prologue in mind, let’s go back to the character of Super Cool, also by Thorne. This comic was distributed in schools to warn children against the dangers of arson and starting fires. What?

The creators’ marketplace hadn’t opened up as it would in the late-1980s and so artists took lots of different types of work. Some designed packaging for products and album covers. Others did work in other fields completely different from drawing. As I said previously, at that time, if you did comics, you did them for the big companies and they owned everything you made. Therefore, you’d better find other means of income.

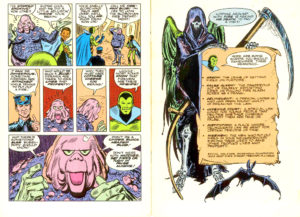

Super Cool is typical of what you’d expect from a superhero from the 1970s timeframe. He is part detective and part otherworldly being. (He has the power to shrink himself down to the size of an earwhig to explore his enemy’s brain.) He has a young sidekick named Fletcher, and he is on the right side of the law in every respect, as two-dimensional as it comes. Considering this was a printed PSA being delivered to elementary schools, I don’t think anyone was looking for rich, multilayered characterization anyway. I’m also sure that the overall language being used in the book was a sincere attempt to speak directly to the reader and be an effective communication tool. In hindsight, the kind of jive-turkey broad strokes being employed here telegraph a few things to readers in the next century. One: the author probably had little actual contact with kids and was not familiar with the street slang. Two: the author was probably a white man who — I assume — came by similar phrases through TV shows like Good Times and maybe What’s Happening!; shows that were well-intentioned narratives about African American families but often were also scripted by white guys. Super Cool is described on the cover as “The Far Out Green.” I don’t know how to translate that.

I haven’t directly called Thorne the writer of the book because mental hygiene pamphlets (such as Super Cool clearly is) are determined by a committee, not necessarily by one creative individual. Make no mistake, this was as much a work-for-hire arrangement as any other, but instead of a Roy Thomas or a Stan Lee filling in dialog boxes after the drawings were put down, you had a table full of educators and academics pondering how to reach “the children.” In the end, Thorne might have shaped the end product and written words, but they would not have originated from him in that form.

And still, Thorne is an accomplished illustrator. Give him full marks for skill even if the end product is painfully earnest in its purpose to warn kids off from playing with matches. You can’t fault the creators of this pamphlet for not trying very, very hard to reach their intended target, and you can’t say they went strictly on-the-cheap. I still wonder, however, if the product fulfilled its purpose or whether the kids of 1974 rolled their eyes and cast out their freebie comics on the way out of the school auditorium.

The previous Comic Retribution article – The Adventures Of Captain Carvel – is available by clicking here.

The previous Comic Retribution article – The Adventures Of Captain Carvel – is available by clicking here.

Comments