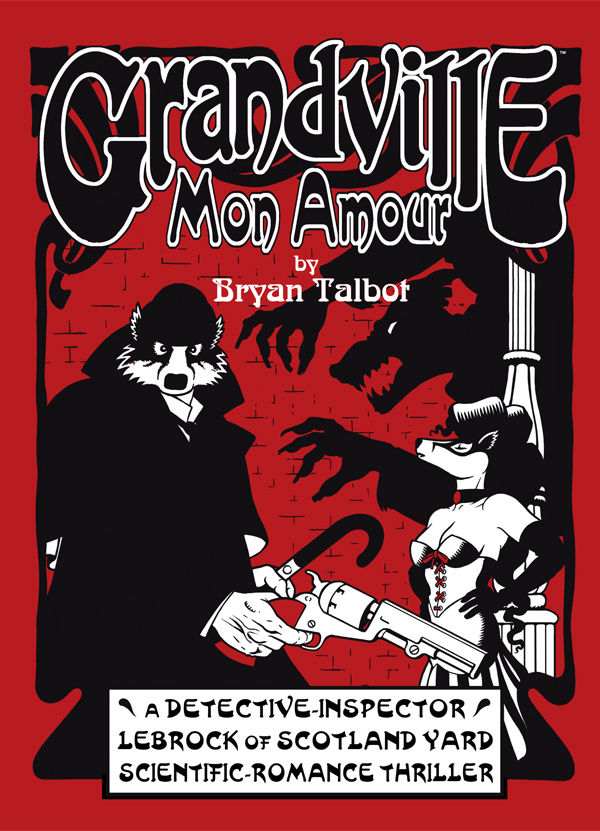

After reading Grandville: Mon Amour, there’s one thing that puzzles me; why are most of Bryan Talbot’s characters in this book animals? Archibald LeBrock, the main character, is a walking, talking badger while his sidekick is a rather dapper looking rodent of some kind. Talbot’s steampunkish Europe is populated by dogs, rams, pigs, hippos, frogs and even the occasional human, who’s mostly just thugs for one of the more socially accepted animals. His Europe, conquered and united by Napoleon around 200 years ago, is falling apart as England has just recently earned its freedom from France and has become a new socialist state. The tension is still high between the two countries so when LeBrock has to travel to France to track down an English killer he finds little help from the local French authorities or his own fellow Englishmen.

After reading Grandville: Mon Amour, there’s one thing that puzzles me; why are most of Bryan Talbot’s characters in this book animals? Archibald LeBrock, the main character, is a walking, talking badger while his sidekick is a rather dapper looking rodent of some kind. Talbot’s steampunkish Europe is populated by dogs, rams, pigs, hippos, frogs and even the occasional human, who’s mostly just thugs for one of the more socially accepted animals. His Europe, conquered and united by Napoleon around 200 years ago, is falling apart as England has just recently earned its freedom from France and has become a new socialist state. The tension is still high between the two countries so when LeBrock has to travel to France to track down an English killer he finds little help from the local French authorities or his own fellow Englishmen.

On the surface, Talbot’s approach to his characters in Grandville: Mon Amour looks a lot like how Juan DÁaz Canales and Juanjo Guarnido approach their Blacksad, published earlier this year by Dark Horse, and their use of animals in a series of grounded detective stories. Thesetypes of animalistic characters are just another way that the cartoonists can tell their story and can be used to an almost infinite number of effects. Canales and Guarnido use the type of animals they pick and even the color of the animals to add layers to their story. Through their choices, they can tell stories about race and national pride. Canales and Guarnido, borrowing a page out of Art Spiegelman’s book Maus, use their design choices as metaphors to advance some aspect of their story.

If those kind of choices exist in Grandville: Mon Amour (or in its predecessor,) they’re far from obvious. Is there any symbology in a badger being a detective? Or a rodent in being his right hand man? If they are there, Talbot doesn’t play with them nearly enough or give any hints to some potential commentary that he may be providing. He’s not interested in drawing connections between the characters and how he represents them. Maybe it’s easy to read something into a hippo being the madame at a French brothel but dogs, frogs and other animals are her prostitutes. There’s little rhyme or reason for his depictions of these characters.

Of course, there is no rule saying that ”the use of anthropomorphic characters shall be accompanied by meaning and allusions that must be clear to the audience.” Comics are filled with talking animal stories that have no hidden meaning behind them other than they’re animals that the artist liked to draw. The problem with Talbot’s character designs is there’s something lacking from his characters. There’s an odd sameness and repetition to the facial expressions of his characters that makes them feel a bit less than real, certainly less real than the wonderfully expressive Guarnido figures in Blacksad. There are two human characters who show up as henchmen in the stories and, with a few simple lines, the expressions that Talbot gives them puts to shame any expressions he gives to his main characters. The henchmen look less like typical Talbot characters and more like something that would have been drawn by Jacques Tardi. It’s a few quick lines on the page but those characters have so much more life and personality in them than LeBrock has in the entire book.

It’s a shame that his art loses some of the character and expression of his figures because Talbot’s story pulls together an intriguing mystery. With the escape of a former war hero or madman (depending on your own views of history) and the race to discover his secrets, Talbot creates a fascinating environment for LeBrock to work in. He’s created a fascinating alternate history world, providing just enough differences to be both recognizable and foreign simultaneously. Relying less on the steampunk aspects and more on the changed historical notes, Talbot ends up with a strong detective story. LeBrock and his sidekick are a more forceful Sherlock Holmes and Watson, caught in a race with their own criminal mastermind.

Talbot’s story about the betrayals of the past and of memory gives the book more heart and soul than his artwork does. With the gripping chases through European streets, the madman who should have been a hero, a detective’s desire for justice, the woman who looks like someone from his past and the victories won by the sacrifices of blood, Talbot’s story is a good, old fashioned page turner as LeBrock races to catch a killer before he strikes again. While the art is unexpressive and stilted, Talbot’s story overcomes the visual weaknesses of Grandville: Mon Amour.

Comments