The voices and music we grow up with stay with us, even when the people who lift those voices in song burn out or fade away. They become part of us, part of our personal and collective DNA, part of the soundtrack that plays in our heads and hearts, tuned to our moods and environment, there when we need them most.

The voices and music we grow up with stay with us, even when the people who lift those voices in song burn out or fade away. They become part of us, part of our personal and collective DNA, part of the soundtrack that plays in our heads and hearts, tuned to our moods and environment, there when we need them most.

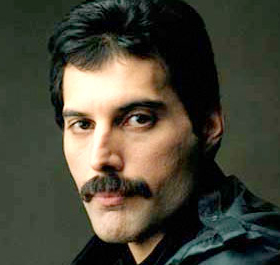

We lost Freddie Mercury 19 years ago this month. I was sitting in one of Rutgers’ massive lecture halls, waiting for a class to begin, when I read the news. I had two newspapers that morning—one local one that printed Mercury’s announcement that he was living with AIDS, and a copy of the USA Today that announced his death—the two pronouncements that, as it turned out, came a single day apart. That he had been ill was saddening, to be certain, but it came as little shock to me—I had seen recent photos of Queen (from the marketing for the band’s then-recent album Innuendo), in which Mercury had looked dreadfully gaunt, almost skeletal—a sure sign at the time that something was amiss.

That he had died, however, sent me into a rush of memory. I recalled the period early in my adolescence, when I would end each day by putting on my headphones and cueing up “Bohemian Rhapsody,” from my little brother’s copy of Queen’s Greatest Hits, which I had at some point appropriated when he jumped on the Duran Duran bandwagon (later, he all but joined Motley Crue—Nikki really should have picked him to replace Tommy in 1999). I recalled the sheer majesty of it all—the orchestral stacking of guitars, the cascading flow of voices, the lyrics that made no sense at all yet still sounded strangely like scripture. It blew my mind nightly for the better part of a year. I don’t think I’ve listened that closely to any other song.

That voice stayed with me.

Even with that daily reminder of Mercury’s greatness, I don’t thing it hit home with me how undeniably crucial he was to Queen until the band toured with Paul Rodgers in 2005. Now, I love Rodgers—Bad Company was a great band; Burnin’ Sky is an under-appreciated classic; and one of these days, I’m going to get a t-shirt made with “Baby I’m a Bad Man” printed on the front and the back. Not to mention that I still fly the flag for The Firm (particularly their Mean Business album), even though Rodgers and Jimmy Page probably don’t. Rodgers possesses one of the great blues rock voices ever, and even at 60 years old, he is a physical and vocal specimen without peer in rock and roll.

Great as he is, to hear him belt out Queen classics like “I Want to Break Free,” “Crazy Little Thing Called Love,” and “Fat-Bottomed Girls” was just wrong on several different levels (though, to be honest, I loved how he handled the rock movement of the live “Bohemian Rhapsody”). To listen to Rodgers and Mercury back to back is to hear the difference two great voices can bring to the same material. Rodgers is steeped in the blues—straightforward and strong, a real throwback to the forebears of his sound.

Mercury, on the other hand, is all hard rock forcefulness and operatic flourish—a perfect storm of Plant and Pavarotti, Jagger and Caruso, Daltrey and Lloyd Webber. Queen music needs that forcefulness and flourish. Absolutely requires it. Theirs is a considerably lesser corpus of work without it.

Mercury’s final living testament to that fact is “The Show Must Go On,” the last track on Innuendo. The man knew he was staring death in the face and channeled through Brian May a set of lyrics that treated the confrontation with all the bravura theatrical flair we had come to expect from him. “Inside my heart is breaking,” he sings, “My makeup may be flaking / But my smile still stays on.”

According to legend, May was uncertain whether Mercury would be healthy enough to sing the song; it required more forcefulness than flourish, and Mercury’s condition had worsened as the sessions had progressed. Mercury responded to May’s concern by throwing back some vodka and recording his vocal in a single take. A single take. Listen to it and tell me that’s not one of the most incredible single-take vocals you’ve ever heard. I almost don’t believe it, even though I very much want to.

According to legend, May was uncertain whether Mercury would be healthy enough to sing the song; it required more forcefulness than flourish, and Mercury’s condition had worsened as the sessions had progressed. Mercury responded to May’s concern by throwing back some vodka and recording his vocal in a single take. A single take. Listen to it and tell me that’s not one of the most incredible single-take vocals you’ve ever heard. I almost don’t believe it, even though I very much want to.

Regardless of the story’s veracity, Mercury’s voice is strong, hitting high notes with such power as to belie his physical weakness, performing, in effect, an act of defiance against the illness ravaging his body. “I’ll face it with a grin,” he boasts, “I’m never giving in / On with the show.” The high note he hits on the last line sends chills through me every time I hear it. It is one of the mightiest displays of Mercury’s vocal prowess in a career full to bursting with such displays.

It’s clichÁ© to say there was no one like Freddie Mercury, but truth trumps clichÁ©—he’s never been matched, never copied, never truly replaced. What he has been is missed, though it is a measure of his strength that in nearly two decades since his death, he still has the power to move, to resonate, and to impact listeners.

His is a voice that has stayed with us, even in his absence from us.

Comments