When “Woman’s World,” the first single from Katy Perry’s latest album arrived, it did so with great confusion, general disdain, and a side of indifference from its target audience.

There were many reasons why. One of the dominant ones was her willingness to work again with the producer Łukasz Gottwald, better known as Dr. Luke. Gottwald was sued by pop star Kesha for “infliction of emotional distress, sex-based hate crimes, and employment discrimination.” Kesha alleged Gottwald engaged in sexual harassment, misogyny, and locking her into a contract where she would be unable to write or record with anyone but him, who she cited as her abuser.

Gottwald remains a controversial figure whose star-maker shine has dimmed under the allegations. And yet, he was central to many of Perry’s biggest hits. Several have taken a dim view of her for bringing him back on for 143, the previously mentioned new album.

As concerning as that is, it is but one aspect that has thrown Perry and her album cycle into the shadows.

A Short Recap

Perry’s first album arrived under her birth name – Katy Hudson – in 2001 in the Christian Contemporary Music (CCM) category. She has spoken frequently about her discomfort in this wing of the music industry, as well as her difficult relationship with her devout parents.

Some of the pop-transgressive attitude of her debut as Perry, 2008’s One Of The Boys, is thanks to that chafing relationship with them. The album’s breakout tracks, “I Kissed A Girl” and “Hot n Cold,” have acidity and petulance reminiscent of a teen testing and taunting the authority figures. These tracks feature a Dr. Luke co-write credit.

The follow-up Teenage Dream followed this formula, launching several of the tracks on it into the Billboard stratosphere.

This record featured the hit, “Firework,” a song that at the time sat easily in the trend of inspirational, affirmational songs that resonated with a young audience grappling with feelings of inadequacy. The intention was well-meant, but time has been less kind to tune. Like “Roar,” from the next album Prism from 2013, there is a veneer of sympathy from the track that barely holds together a string of cliches hinting at strength and self-actualization, yet leaving the listener with a frustratingly hollow, unspecific sentiment. “Why do you say I’m the best,” one asks. The answer rendered is a hollow, “Oh, just because.”

This leaves the songs as much like audio versions of corporate motivational posters of a mountain or a cat hanging onto a rope. It tells you to feel good without actually understanding your situation or caring if you do so or not. It is brash, bold, and as empty as “thoughts and prayers.” But these were hits and struck a chord regardless, and so Perry added this second dimension to her persona: she was the over-sexualized, smirking goofball who also told you that you were awesome just as you are.

There was a conscious break – theoretically – with 2017’s Witness, leaving Dr. Luke behind. She dubbed this new phase of her career “purposeful pop,” and claimed she was backing away from the naughty girl vibe of her past. She was shaken, disillusioned, and looking for a different purpose.

But it is shockingly divided. The socially-conscious songs had to compete with others that stayed firmly in that old lane, the one which needed to stay a star no matter what, overexposure and/or bust (see “Bon Appetit“). She was uttering regrets for past frivolities while engaging in the same in a flurry of mixed messages.

But it is shockingly divided. The socially-conscious songs had to compete with others that stayed firmly in that old lane, the one which needed to stay a star no matter what, overexposure and/or bust (see “Bon Appetit“). She was uttering regrets for past frivolities while engaging in the same in a flurry of mixed messages.

Perhaps more destructive was a feud with Taylor Swift, and we all know how that goes. The track “Swish Swish” was a clap-back to Swift’s “Bad Blood,” and fell flat on its face. There would eventually be a sort of reconciliation, with Perry showing up at the end of the video for Swift’s “You Need To Calm Down,” but the shine did not return.

Three years later, Perry’s Smile found her in a relationship with Orlando Bloom, being a new mom, and looking to continue on the road to maturation. The record did not do well.

And now, four years later, she’s rolling out 143.

The Real Katy?

“Woman’s World” arrived with a combination of the surface-level platitudes and “girl boss” motivation and kudos of previous hits paired with imagery of lots of skin and innuendo. It wanted to be sexy and suffragette at the same time, and the overall reaction was, at minimum, squicky. Reviewers, trying to be fair and not reduce their confusion to a string of nasty complaints focusing only on her overt presentation, regularly stated a bland vote of no confidence and moved on. It was safer to be indifferent than to risk saying something that could be accused as “slut-shaming.” There was something about the “Woman’s World” video that resembled a trap, with bikinis and gyrations just under the box with the pull string and stick precariously propping it up. “I dare you to criticize this pro-women sentiment,” it appeared to taunt. The bait was not taken by most.

Reacting to the tepid response and critiques, Perry would tweet out later, “It’s satire!” like the person who said something hurtful and then backtracks, “It was just a joke! Can’tcha take a joke?”

Additional promotion for the record pictures her on the cover as topless and shimmering, surrounded by the aura of a heart. It is meant to remind one of the Teenage Dream cover and seems to refute the past two albums’ chaste depictions. Her ongoing Instagram campaign has her ever-clothed in scanty tops, and sometimes just in a bikini, bending over so that all which is seen of her is the barely covered bottom, seemingly putting up another trap. “I dare you to look at this and say anything about it. Check this out!”

Additional promotion for the record pictures her on the cover as topless and shimmering, surrounded by the aura of a heart. It is meant to remind one of the Teenage Dream cover and seems to refute the past two albums’ chaste depictions. Her ongoing Instagram campaign has her ever-clothed in scanty tops, and sometimes just in a bikini, bending over so that all which is seen of her is the barely covered bottom, seemingly putting up another trap. “I dare you to look at this and say anything about it. Check this out!”

It’s not shocking, though. Nor is it as titillating as the marketing team thinks it will be. And crucially, it represents an older, far different (though not extinct) pop playbook than is in vogue now.

What’s The Real Problem

Let’s get this out of the way first. It’s not the heavy reliance on sexuality that is failing the marketing of Perry’s 143. A scan of the pop charts and the accompanying videos will disabuse you of that notion and a woman owning her femininity however she chooses to is her right. If you are offended by your perception of a prurient artist, it’s up to you – not them – to leave that work behind.

But there is a change happening, at least in the presentation of pop, but also in what being a star means.

One of the biggest albums of the summer of 2024 was Charli XCX’s brat. She has never shied away from a pin-up aesthetic on her album covers in the past but this one was aggressively anti. It sported a screaming fluorescent green square with the title emblazoned across it in black, lower-case letters.

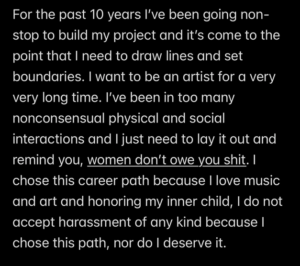

Another artist having a big year is Chappell Roan, who has been outspoken in their beliefs about modern celebrity and has not been afraid to defend their boundaries. Their post from August is vastly different from the open-book-anything-for-fame demeanor of so much personal branding from celebs in the past.

A huge avatar of this shift has been Billie Eilish, showing that there was a place for all kinds of personae in the pop world, not solely the cliched sex-kitten.

And yet, there’s also room for someone who seems to follow – at least in spirit – the music’s flirtatious infatuation, like Sabrina Carpenter, who made huge strides over the summer. She, unlike her contemporaries, feels more at home in a stardom of the past, a stardom not unlike Perry’s had been.

We have a landscape where both extremes can co-exist. It’s neither about embracing nor refuting what came before. Why isn’t it working for Katy Perry?

Largely, I think people are put off by how badly she wants and needs her fame back. It’s not just about the glamour poses, working with sketchy collaborators again, the reiteration of surface-level platitudes like so much feel-good starch in the bloodstream, all temporary rush with no long-term benefits. It sounds rude to use the term “desperate” and it causes this writer to cringe in needing to, but what else is there? Katy Perry has crossed almost every red line she imposed and was adamant about promoting. Her purposeful pop has turned backward to a time when she was building her career, needling her evangelical parents as a side effect.

Whereas Charli XCX seems poised to own her risk, and Chappell Roan stands their ground in saying, “You don’t own me,” Perry and the songs on 143 reverberate, “Just love me the way you used to,” and it is deeply uncomfortable.

Comments