When one speaks of “bad” movies, it is necessary to take care to not lump all kinds of movies into one singular pile. Some movies are plainly inept, poorly written, poorly executed, bad dialogue, bad acting, and rightly criticized. Others are just misguided, not lost causes, but a conglomerate of choices that could have been better. Krull (1983) is, in my opinion, firmly in the latter category.

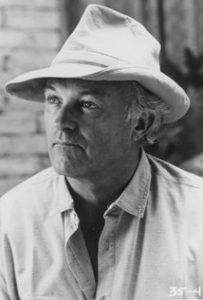

The talent on-hand certainly wasn’t lacking. Director Peter Yates is better known for films like Bullitt, Eyewitness, and Breaking Away. The Director of Photography is Peter Suschitsky who shot The Empire Strikes Back. Among the actors in the film are highly respected individuals of the British stage and film industry like Freddie Jones and Bernard Bresslaw, and future stars Liam Neeson and Robbie Coltrane. James Bond effects guru Derek Meddings handled visual effects, James Horner did the score, and Ray Lovejoy edited the film. His credits extend from 2001: A Space Odyssey to Tim Burton’s first Batman film and more. What I think I’m saying here is that, on a technical level, Krull is about the best as you could have hoped to have from a fantasy movie at that time.

The talent on-hand certainly wasn’t lacking. Director Peter Yates is better known for films like Bullitt, Eyewitness, and Breaking Away. The Director of Photography is Peter Suschitsky who shot The Empire Strikes Back. Among the actors in the film are highly respected individuals of the British stage and film industry like Freddie Jones and Bernard Bresslaw, and future stars Liam Neeson and Robbie Coltrane. James Bond effects guru Derek Meddings handled visual effects, James Horner did the score, and Ray Lovejoy edited the film. His credits extend from 2001: A Space Odyssey to Tim Burton’s first Batman film and more. What I think I’m saying here is that, on a technical level, Krull is about the best as you could have hoped to have from a fantasy movie at that time.

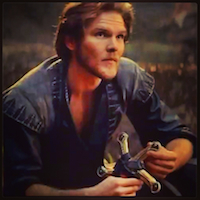

Therein lies the problem. It’s a film that cannot fully commit to being a fantasy film. Krull is not some earthbound Middle Earth type of imagined land. It is a planet where, apparently, sword and sorcery and swashbuckling have found a home. The story, in a nutshell, is that two adversarial families will have to merge, as the marriage of Prince Colwyn (Ken Marshall) and Princess Lyssa (Lysette Anthony) is impending. An evil alien outpost in the form of a mountain sits down upon the world of Krull. The minions of its evil inhabitant kidnap the princess in the middle of her vows to Colwyn. Almost everyone else, including their fathers, are killed in the battle. Because these are space invaders, they have laser-firing staves, like you do. When the minions are defeated, they retreat from the skulls of the bodies as bloodied crab-like creatures and burrow into the ground, which should be obvious to any dimwit.

Therein lies the problem. It’s a film that cannot fully commit to being a fantasy film. Krull is not some earthbound Middle Earth type of imagined land. It is a planet where, apparently, sword and sorcery and swashbuckling have found a home. The story, in a nutshell, is that two adversarial families will have to merge, as the marriage of Prince Colwyn (Ken Marshall) and Princess Lyssa (Lysette Anthony) is impending. An evil alien outpost in the form of a mountain sits down upon the world of Krull. The minions of its evil inhabitant kidnap the princess in the middle of her vows to Colwyn. Almost everyone else, including their fathers, are killed in the battle. Because these are space invaders, they have laser-firing staves, like you do. When the minions are defeated, they retreat from the skulls of the bodies as bloodied crab-like creatures and burrow into the ground, which should be obvious to any dimwit.

The point is that the credited screenwriter Stanford Sherman (Any Which Way You Can, The Ice Pirates, the ’60s TV version of Batman) threw in everything — the one-eyed lurker, the flying horses, the magician who changes into animals, everything — into the script without a care for how it all bunched up like a floor mat before a door. But give him credit. That “what the hell, we’ll just chuck it in there” abandon is part of the fun. And it is fun, as goofy as it all becomes by the end. Everyone is taking this stuff so, so, so seriously. Lines about kings and kingdoms and “the glaive,” a kind of a ninja star after a growth spurt, are delivered with Shakespearean gravitas. Marshall, as Colwyn, is alternately making a sandwich of the scenery or is so chilled out he seems completely apart from the danger occurring all around him. These are not things you quibble about when you’re watching the movie.

There are the usual plot holes, like the flying “firemares.” Whenever you introduce a flying animal into a story, you’re entertaining a dangerous proposition, dangerous to the credibility of the story and to that all imperative suspension of disbelief. You will ask, “Why did you allow half of your questing fellowship to bite it if you knew, even in mythological terms, there was a flying animal to help you out? If you could fly over a giant chasm, you could fly away from danger and get more forces to the attack point, right?” This and other logical assumptions are wasted on a movie that asks you to chuck out logic and just saddle up.

Lysette Anthony was very critical of the film during her commentary on the Krull DVD, and she has a legitimate reason to be. “They cast me because I was young and pretty…and had a lot of hair! The hair stayed,” she joked. What she meant was that almost everything else that should have been built into her character was missing, including her voice. While almost everyone else in the film spoke with a British accent, Ken Marshall did not. It is assumed that the producers wanted Colwyn and Lyssa to pair up, so rather than just being young and attractive, they also had American accents. To achieve this for Lyssa, Lysette Anthony’s voice was dubbed over by American actress Lindsey Crouse.

Lysette Anthony was very critical of the film during her commentary on the Krull DVD, and she has a legitimate reason to be. “They cast me because I was young and pretty…and had a lot of hair! The hair stayed,” she joked. What she meant was that almost everything else that should have been built into her character was missing, including her voice. While almost everyone else in the film spoke with a British accent, Ken Marshall did not. It is assumed that the producers wanted Colwyn and Lyssa to pair up, so rather than just being young and attractive, they also had American accents. To achieve this for Lyssa, Lysette Anthony’s voice was dubbed over by American actress Lindsey Crouse.

Indeed, Lyssa was gorgeous, but that was really all she was, beyond a prop to motivate the action (IE: save the princess before the alien demon takes her waiting wedding vow and steals dominion over Krull). When opportunities arrive to exert any level of agency, Lyssa quickly drops them like a sword that’s too heavy. I suspect that’s Anthony’s major qualm with the film, and one she was not prepared to argue down. Again according to her commentary, she was “straight out of convent school” and was likely told she was lucky just to have been there. Lyssa was relegated to being little more than another “Princess Peach” waiting for Super Mario to defeat King Koopa. That’s kind of what Krull is.

Yet there are plenty of reasons to still watch it, and that got me thinking. If I consider this a “bad” film by conventional standards, what makes a good “bad” film? First, you have to have engaging performers, not necessarily performances. The character of Torquil, played by Alun Armstrong (The Mummy Returns), is at first a total scoundrel, loyal only to himself, and not to be trusted beyond his merry band of n’er-do-wells. But he quickly proves himself, and never once does he break out his flute for a rollicking rendition of “Bungle In the Jungle.”

Yet there are plenty of reasons to still watch it, and that got me thinking. If I consider this a “bad” film by conventional standards, what makes a good “bad” film? First, you have to have engaging performers, not necessarily performances. The character of Torquil, played by Alun Armstrong (The Mummy Returns), is at first a total scoundrel, loyal only to himself, and not to be trusted beyond his merry band of n’er-do-wells. But he quickly proves himself, and never once does he break out his flute for a rollicking rendition of “Bungle In the Jungle.”

David Battley’s magician character Ergo is the blatant comedy relief for the band of misfits setting out to save the princess. Sharp-eyed observers will possibly recognize Battley as the original “Stig O’Hara” from the initial skits about The Rutles from Eric Idle’s Rutland Weekend Television series. His schtick doesn’t always land gracefully but does work often enough to alleviate some of the movie’s heavy-handed moments. He is, in the grand tradition, not very good at what he does which causes endless mishaps, but these moments afford the filmmakers a crack at a few interesting pre-CGI visual effects. As has been previously stated, there’s a lot to look at in Krull.

Investment is important. I feel like every person who worked on the film committed everything they had (some to their detriment) and they absolutely believed this was a story that could go on in some franchise capacity. I’ve never been a fan of the wink-and-nod approach to fantasy-science-fiction films (unless they are intended to be satirical). If the characters themselves aren’t buying in, why should I? For all its flaws, Krull doesn’t suffer that one.

But it has not had much of a second life as a good “bad” film. It is not an incompetent disaster. It works as an entertainment, and you could get lost in it for a couple of hours with ease. It seems like we reached a turning point, perhaps a decade ago, where an entertainment has to be so over-the-top great or so over-the-top awful that there’s no room in or consideration of the middle. Think of Tommy Wiseau’s The Room which is so bad that you never have to doubt it or ask another soul, “Is this as bad as I think it is?” This kind of all-or-nothing need strikes me the same way that sitcom laugh tracks do. As those presume to tell you, “You should be laughing here,” movies have to take all the guesswork away from the viewer so they don’t have to ask questions and possibly look foolish. You know, from frame one, this is good or really, really bad, and you don’t have to bicker about it to anyone.

So maybe the real sin Krull commits is that it is too good to be the butt of the joke but not good enough to be remembered beyond the fuzzier corners of the cult film world. That’s a lousy position to be in.

Comments