Okay, this is how I think it’s going to go down: before the end of the year, a major player in the music industry will announce that it’ll no longer sign bands to make albums. It’ll institute ten-song deals versus three albums, the product to be delivered over a two-year period versus a contract tying up five to ten years. Each of the ten songs are to be considered singles, radio-ready, with at least a 65 percent probability of hit status, otherwise the band in question is liable to be dropped for fulfillment issues. If the losses are great, breach-of-contract litigation is not out of the question.

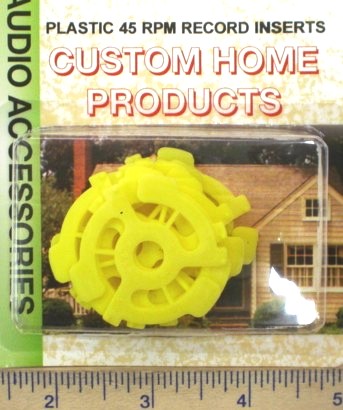

Sound ridiculous? Or does it sound like the obvious conclusion for an industry that continues to lose money and customer patronage, seeking to cut away anything that doesn’t promote profit — album tracks that may appeal to a creative sense but can’t be capitalized upon, extra production costs inherent in those tracks, and design, packaging, and promotion of a product the public only wants 10 percent of. Witness the next music-industry model circa 2010: the business model of 1961. A label executive now sees his competition focused solely on bankrolling hits, not album sides or expensive packaging, and has to mull over whether it’s better business-wise to chop his staff in half or chop his label’s output in half, retaining the profitable side for himself. Of course the second option is better. He follows suit, and the business model we know today ceases to exist.

Sound ridiculous? Or does it sound like the obvious conclusion for an industry that continues to lose money and customer patronage, seeking to cut away anything that doesn’t promote profit — album tracks that may appeal to a creative sense but can’t be capitalized upon, extra production costs inherent in those tracks, and design, packaging, and promotion of a product the public only wants 10 percent of. Witness the next music-industry model circa 2010: the business model of 1961. A label executive now sees his competition focused solely on bankrolling hits, not album sides or expensive packaging, and has to mull over whether it’s better business-wise to chop his staff in half or chop his label’s output in half, retaining the profitable side for himself. Of course the second option is better. He follows suit, and the business model we know today ceases to exist.

Now, you as a music fan and album purchaser hear this news and are appalled — what about the creative angle, the cohesive whole, and the notion that an artist has the broadest canvas with which to work, expand, and grow? Well, what about it. It was recently reported that Apple’s iTunes is now the dominant provider of music in the world, bigger than electronics stores that stock CDs as loss leaders, bigger than even monolithic Wal-Mart, which itself was once the king of music retail. iTunes has made its bones on singles, pure and simple. Few of the portal’s primary users actually go for album sides; people with that mind-set are still likely to buy the physical product, but their numbers are dwindling fast. To say the public in general will miss the album is to ignore the obvious — not only won’t they miss it, they haven’t missed it for five-plus years and counting.

Safe money is on EMI USA being the first to pull the trigger. It’s been on the industry’s ragged edge for a long time now, as superconglomerates Universal Music and Sony/BMG continue to eat everything in sight. Universal’s rise is the most stunning since its flagship label in the late ’80s and early ’90s, MCA, was on the verge of dying: Tom Petty jumped ship for Warners, MCA hadn’t broken a new rock act in about a decade, and it was failing on its initial acquisitions of acts dropped by other labels. Then the company bought up Geffen/DGC. Then Nirvana blew up. Then it dawned on Universal: Don’t buy the bands. Buy the labels. In the wake of boardroom binging, there’s not much left for EMI to eat up. Even its highest-profile artists, like Radiohead, have taken off for greener pastures. The time is right for EMI’s own hallelujah moment; reverting to the singles market is that exact “hosanna.”

Safe money is on EMI USA being the first to pull the trigger. It’s been on the industry’s ragged edge for a long time now, as superconglomerates Universal Music and Sony/BMG continue to eat everything in sight. Universal’s rise is the most stunning since its flagship label in the late ’80s and early ’90s, MCA, was on the verge of dying: Tom Petty jumped ship for Warners, MCA hadn’t broken a new rock act in about a decade, and it was failing on its initial acquisitions of acts dropped by other labels. Then the company bought up Geffen/DGC. Then Nirvana blew up. Then it dawned on Universal: Don’t buy the bands. Buy the labels. In the wake of boardroom binging, there’s not much left for EMI to eat up. Even its highest-profile artists, like Radiohead, have taken off for greener pastures. The time is right for EMI’s own hallelujah moment; reverting to the singles market is that exact “hosanna.”

The album will never totally die out, of course. Indie labels will still champion it, and the major labels, once they’ve amassed 10 or 15 hits from an act, will release greatest-hits packages just as labels in the ’50s and ’60s did. With the popularity of “various artists” collections like the Now That’s What I Call Music series, it’s not unlikely that Universal or Columbia would institute their own series of such collections — think of a “Columbia All-Stars” compilation or an “Interscope Bangin’ Hits” in this notion. Again, not a new idea, as Atlantic and Motown thrived on such concepts for a long time before the paradigm shift, before the Beatles.

Yes, even though other artists dabbled with the inclusive collection format, it was the Beatles who really solidified the album as the dominant medium, and it could be argued that by crippling our current system we’re stifling future bands with such import and creative impulse. The iTunes business model has already done that, but bands with such ambitions will still find a way, even if it means bankrolling their DIY inclinations themselves. They’ll never be as big as the Beatles, though, and there will never be an album as huge as Michael Jackson’s Thriller again. Selective purchasing, just like selective breeding and genetics, will see to that.

There is a bright side, though — many of today’s top artists don’t deserve to make full albums. They and their phalanx of producers, writers, and “people” truly only have two or three good tunes in them. Woe to the uninformed who buy one of their albums and find 80 percent of it to be crap. The singles are essentially the best jokes in a movie trailer that serve to sell the movie, but after you’ve plunked down your $12 you realize they’re the only jokes in the movie. It’s apparent that in the future record labels will only pay for those good jokes in the first place, forcing artists to deliver them and contractually binding them to the promise. Good news for pop music aficionados indeed.

There is a bright side, though — many of today’s top artists don’t deserve to make full albums. They and their phalanx of producers, writers, and “people” truly only have two or three good tunes in them. Woe to the uninformed who buy one of their albums and find 80 percent of it to be crap. The singles are essentially the best jokes in a movie trailer that serve to sell the movie, but after you’ve plunked down your $12 you realize they’re the only jokes in the movie. It’s apparent that in the future record labels will only pay for those good jokes in the first place, forcing artists to deliver them and contractually binding them to the promise. Good news for pop music aficionados indeed.

I’m certain the death of the major-label album will happen before year’s end; it’ll be huge news and will irrevocably change mainstream music creation forever, just as the iPod has changed the buying and listening habits of consumers. Form follows function. I sympathize with fans of the good old album because I’m one myself, but c’mon — we knew it was coming. We just needed to admit it, that’s all.

Comments