As you might have seen already, a lot of favorite columns and writers from Popdose’s now nine years of life are returning. I couldn’t be happier about this, and to prove it, I’m going to horn in on everyone’s thunder like the weird kid with the wonky knee who’s got to be on the kickball team too! (I do resemble this remark, so clam up, all you weird kids with wonky knees.) Dw. On… returns to the site in a monthly configuration.

Now the pressure’s on. When you bring back something like a regular column, you better start off big, or else the whole thing is meaningless. I think I have the solution because in the whole of film history there are few examples bigger than Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane. That wasn’t always the case. In its first appearance in 1941, the film was already excoriated by some, loathed by others, and feared by still others who worried about the movie’s knock-on effect on the whole film industry. It did very poorly at the box office when measured against the effort that went into the film’s creation. Its celebrity came several years later when it was revisited by fresh audiences able and equipped to deal with the new cinema Welles was offering up.

Now the pressure’s on. When you bring back something like a regular column, you better start off big, or else the whole thing is meaningless. I think I have the solution because in the whole of film history there are few examples bigger than Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane. That wasn’t always the case. In its first appearance in 1941, the film was already excoriated by some, loathed by others, and feared by still others who worried about the movie’s knock-on effect on the whole film industry. It did very poorly at the box office when measured against the effort that went into the film’s creation. Its celebrity came several years later when it was revisited by fresh audiences able and equipped to deal with the new cinema Welles was offering up.

In the past five years, the movie has lost a bit of its shine to the critical community, with Casablanca and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo regularly jostling with it for the lead position of the 100 Greatest American Films. Further, even these stalwarts are being challenged by the new crop who view anything after 1965 to be cinematic vegetables. This backing off is, in part, because of the passing of so many of the critics who championed Citizen Kane. Another might be the way home video has changed everything. The viewer is no longer bound by the occasional airing on PBS and are, instead, bombarded by new content flying at them from every angle the Internet provides. The echo chamber that gave Citizen Kane so much prominence is gone.

In the past five years, the movie has lost a bit of its shine to the critical community, with Casablanca and Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo regularly jostling with it for the lead position of the 100 Greatest American Films. Further, even these stalwarts are being challenged by the new crop who view anything after 1965 to be cinematic vegetables. This backing off is, in part, because of the passing of so many of the critics who championed Citizen Kane. Another might be the way home video has changed everything. The viewer is no longer bound by the occasional airing on PBS and are, instead, bombarded by new content flying at them from every angle the Internet provides. The echo chamber that gave Citizen Kane so much prominence is gone.

Nonetheless, I think a resurgence of interest in the film is going to come, and much faster than anyone has planned.

I’m getting ahead of myself. The first thing to recognize is that Citizen Kane was probably the first studio-funded, studio-released American film that took surrealism to heart. From its montage-driven jumps from past to present to past again; its visuals which dared to use mirror reflections, lens distortion, and hyper-extended depth-of-field as narrative devices; and a new level of special visual effects reliance that depicted wealth and grandeur not seen on film up to that time, this movie shot for a reality so much closer to our experience. In doing so, it blew right past.

________________________

If you haven’t seen the movie by now, you probably never will. Here is a synopsis of the story:

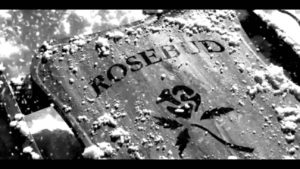

Media magnate Charles Foster Kane (Welles) has died. He outlived his first wife and son, leaves behind a second wife whom he attempted to mold into a star, something she never wanted. His mansion Xanadu, named after a reference from the epic poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, is filled with collected bric-a-brak, in every corner, and around every turn. With all this, his last dying word is the mysterious “Rosebud.”

A reporter is tasked with interviewing those who remain — business partners, former lovers, even the witness of Kane’s dead surrogate father — to get a grasp on what or who Rosebud is. Why was this the final thought in his mind, the last statement from his mouth?

A reporter is tasked with interviewing those who remain — business partners, former lovers, even the witness of Kane’s dead surrogate father — to get a grasp on what or who Rosebud is. Why was this the final thought in his mind, the last statement from his mouth?

The reporter learns that Kane was not born with that silver spoon in his mouth, the one he claimed he always gagged on. He was a relatively happy boy living with his parents who ran a boarding house in Colorado. Sadly, the bank has come to take what is owed, more than the Kanes can pay. A deal is struck by the parents with the wealthy Walter Parkes Thatcher (George Couloris) who will take young Charles as his ward. Kane’s mother is numbed to the great sacrifice she will make. His father protests until he gets another earful of the financial benefit of seeing his son off. Thatcher wants an heir. In the middle of this triad is heartbroken Charles who will learn a hard lesson about wealth and getting what you want far too soon.

When he comes of age, the rebellious Kane insists he wants a newspaper company. It is but one more thing to add to the growing collection thinks Thatcher as he derisively quotes Kane’s telegram to him: “I think it would be fun to run a newspaper.” Thatcher acquiesces to the request but probably shouldn’t have. Kane uses The New York Inquirer as a weapon against him, taking his vendetta past his surrogate father to the places that will hurt him the most: the businesses that fuel his wealth.

When he comes of age, the rebellious Kane insists he wants a newspaper company. It is but one more thing to add to the growing collection thinks Thatcher as he derisively quotes Kane’s telegram to him: “I think it would be fun to run a newspaper.” Thatcher acquiesces to the request but probably shouldn’t have. Kane uses The New York Inquirer as a weapon against him, taking his vendetta past his surrogate father to the places that will hurt him the most: the businesses that fuel his wealth.

It’s in these early scenes where the audience ought to see where Kane’s trajectory lies. Sure, he looks like a socialist firebrand to his schoolmate and partner in journalism, Jedediah Leland (Joseph Cotten) and his unwavering, loyal paper associate Bernstein (Everett Sloane), but Kane’s driving interest is in getting back the past, or making those pay who took the past from him. At every turn, when he’s not accumulating something that he presumes will never be taken away from him, he’s waging a war on those who would reject him in any sense. In a particularly telling scene, Kane has just jotted down on a scrap of paper what he calls his manifesto of principles. We’ll see throughout the movie this is not a to-do plan as much as a to-undo plan. Just before this declaration, Leland comments on Kane’s appetite, still shoveling food into his face, “You’re still eating?”

Kane shoots back, “I’m still hungry!”

Kane shoots back, “I’m still hungry!”

Soon the Inquirer is growing, thriving, and stealing away the honored staff from its competitors. His network of newspapers stretches across the nation. Kane is learning about the perks of power and influence. Roger Ebert once said that this section of the film is where Kane gives in to the pleasures of the flesh, but my take is different. Up to this point, Kane’s been a poor little rich boy. Now he’s a man figuring out that money is only a paper manifestation of what he craves: power. With power, you can achieve constancy. No one leaves you when you’re in control. Whether he’s actively angling for power or it whether he crosses it like another marble statue he simply must have, that’s up for grabs. After passive-aggressively announcing to his staff that he is engaged to be married to the president’s niece (Ruth Warrick), Bernstein muses, “President’s niece? By the time he’s done, she’ll be a president’s wife!”

The Inquirer continues to rake the muck, collecting powerful enemies like New York Governor Jim Gettys (Ray Collins). It is not the newspaper’s stories that directly raise Gettys ire, it’s the fact that the brazen neophyte Kane is gunning for Big Jim’s job. Through Gettys, Kane is revealed to be having an extramarital relationship with mild shopgirl Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore). The revelation shocks the country and kills his governor’s race, effectively ends his marriage, and plunges Kane’s world into a scandal. He will not be diminished. He’s still rich and he is still, technically, married into political power. That is until his wife and son die in a car wreck. Kane is now free to marry Susan and make her into an opera star — yet another act of him imposing his will upon others without their input. Susan likes to sing but is not a singer, yet there she is, on a stage in a new production meant to shock and delight the world. Instead, she is brought to embarrassment.

The Inquirer continues to rake the muck, collecting powerful enemies like New York Governor Jim Gettys (Ray Collins). It is not the newspaper’s stories that directly raise Gettys ire, it’s the fact that the brazen neophyte Kane is gunning for Big Jim’s job. Through Gettys, Kane is revealed to be having an extramarital relationship with mild shopgirl Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore). The revelation shocks the country and kills his governor’s race, effectively ends his marriage, and plunges Kane’s world into a scandal. He will not be diminished. He’s still rich and he is still, technically, married into political power. That is until his wife and son die in a car wreck. Kane is now free to marry Susan and make her into an opera star — yet another act of him imposing his will upon others without their input. Susan likes to sing but is not a singer, yet there she is, on a stage in a new production meant to shock and delight the world. Instead, she is brought to embarrassment.

It falls to Jedediah Leland to write the review. Will he protect his job and say what Kane wants and expects, or will he hew to the young Kane’s declaration of principles and tell the truth, even though he knows it is a knife in the back in most respects. Kane finds Leland passed out drunk before a typewriter. The half-completed review is scathing. Kane finishes it not in his preferred manner, but in the way Leland intends, and then fires him. Later on, the paycheck for the article returns to Kane, torn in shreds, and enveloped in that manifesto of his. One more piece of Kane’s world which he wanted to hold on to forever, returned in pieces and lost to the future.

It falls to Jedediah Leland to write the review. Will he protect his job and say what Kane wants and expects, or will he hew to the young Kane’s declaration of principles and tell the truth, even though he knows it is a knife in the back in most respects. Kane finds Leland passed out drunk before a typewriter. The half-completed review is scathing. Kane finishes it not in his preferred manner, but in the way Leland intends, and then fires him. Later on, the paycheck for the article returns to Kane, torn in shreds, and enveloped in that manifesto of his. One more piece of Kane’s world which he wanted to hold on to forever, returned in pieces and lost to the future.

Susan attempts suicide. Kane tries to keep her together, to protect her. Eventually, she decides protection means being as far from “Charlie” as possible. I realize that at this stage this all sounds like soap opera, but it is actually the point of the movie. This is the making and unmaking of a man, at first fueled by his flames of ambition and need to thwart abandonment, then consumed by those flames…much like his beloved childhood sled is consumed in a furnace at the very last of the film. The name of the sled is “Rosebud.” It is not that, after all this relentless collecting, what he really wanted was that sled. It is a symbol of the life he could have had if the corrosive power of the world hadn’t tainted his little snow covered Eden in Colorado before his father sold him out to the rich Mr. Thatcher.

Susan attempts suicide. Kane tries to keep her together, to protect her. Eventually, she decides protection means being as far from “Charlie” as possible. I realize that at this stage this all sounds like soap opera, but it is actually the point of the movie. This is the making and unmaking of a man, at first fueled by his flames of ambition and need to thwart abandonment, then consumed by those flames…much like his beloved childhood sled is consumed in a furnace at the very last of the film. The name of the sled is “Rosebud.” It is not that, after all this relentless collecting, what he really wanted was that sled. It is a symbol of the life he could have had if the corrosive power of the world hadn’t tainted his little snow covered Eden in Colorado before his father sold him out to the rich Mr. Thatcher.

________________________

Lots of things are assumed about Citizen Kane. That it is a hatchet job against its closest real-life parallel, the life of media mogul William Randolph Hearst, that Hearst too started with good intentions but was quickly consumed by varying lusts. Hearst is famous for the quote regarding the Spanish-American War whereby Hearst was found to be less than a scrupulous journalist: “You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.” Hearst’s mansion San Simeon is a source for Xanadu’s reflection. And also, Hearst’s relationship with comedic actress Marion Davies was a tipping point for the newspaper magnate, as the Susan Alexander character seemed to be a thinly-veiled jab there as well.

Lots of things are assumed about Citizen Kane. That it is a hatchet job against its closest real-life parallel, the life of media mogul William Randolph Hearst, that Hearst too started with good intentions but was quickly consumed by varying lusts. Hearst is famous for the quote regarding the Spanish-American War whereby Hearst was found to be less than a scrupulous journalist: “You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.” Hearst’s mansion San Simeon is a source for Xanadu’s reflection. And also, Hearst’s relationship with comedic actress Marion Davies was a tipping point for the newspaper magnate, as the Susan Alexander character seemed to be a thinly-veiled jab there as well.

Hearst declared his own war on Welles, and Hearst’s staff of writers and hangers-on assailed him, RKO Pictures, co-screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, and anyone else accidentally found on the studio lot with equal aggression. The air was so poisonous, Louis B. Mayer, the head of MGM Pictures offered RKO full payment of Citizen Kane‘s productions costs just to burn the negative and clear the air. RKO gave a lot of money and an unprecedented amount of power to wunderkind Welles — take note: he was only in his twenties when he made the film — and sticking by him probably felt like acceptance of this cancer. Obviously, the negative was never sold off.

Hearst declared his own war on Welles, and Hearst’s staff of writers and hangers-on assailed him, RKO Pictures, co-screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, and anyone else accidentally found on the studio lot with equal aggression. The air was so poisonous, Louis B. Mayer, the head of MGM Pictures offered RKO full payment of Citizen Kane‘s productions costs just to burn the negative and clear the air. RKO gave a lot of money and an unprecedented amount of power to wunderkind Welles — take note: he was only in his twenties when he made the film — and sticking by him probably felt like acceptance of this cancer. Obviously, the negative was never sold off.

Thing is, while Hearst’s life story informed the screenplay, so did the lives of many powerful people who were likely equally incensed by this snot-nosed punk who only a year or so before caused national frenzy when his radio adaptation of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds caused an actual panic in America, with listeners believing Martians had invaded. Yet the movie is also a reflection of the moviemaker himself, as well as a self-fulfilling prophecy. Welles could not know that he would never have that level of control over his movies again, that he wouldn’t be trusted not to rake his own muck. In his early days, his dutiful mother and stepfather (named, in a nice bit of homage, “Bernstein”) strove to build Welles up. He became a star of stage and radio, including holding the plum job of voicing pulp hero The Shadow. He was, in so many ways, just like that first quarter of Citizen Kane where Charles was ascendant.

Another assumption is that Kane is little more than a manipulative, power-mad creep who chews up and spits out associates rapaciously because, as he said, “I’m still hungry.” It’s a fast takeaway, but Kane’s character is far more tragic than that. Here’s a guy that, even with all the money in his possession and a bullhorn as big as his mouth, had no agency. His life seems like it is in complete self-control, but it is so far from that. Each major life event is precipitated by another person. Thatcher’s deal. Gettys’ exposing his affair. The death of his wife and son. His inability to love Susan for who she was and not try to shadow her into being what he wanted her to be. That’s the main point. Power is temporary and not very powerful. People do have minds of their own and are prone to use them once in a while. You may not like how.

Another assumption is that Kane is little more than a manipulative, power-mad creep who chews up and spits out associates rapaciously because, as he said, “I’m still hungry.” It’s a fast takeaway, but Kane’s character is far more tragic than that. Here’s a guy that, even with all the money in his possession and a bullhorn as big as his mouth, had no agency. His life seems like it is in complete self-control, but it is so far from that. Each major life event is precipitated by another person. Thatcher’s deal. Gettys’ exposing his affair. The death of his wife and son. His inability to love Susan for who she was and not try to shadow her into being what he wanted her to be. That’s the main point. Power is temporary and not very powerful. People do have minds of their own and are prone to use them once in a while. You may not like how.

__________________________________

So why do I think this film is ready for yet another reappraisal?

Aside from obvious touchpoints — so obvious that I’m not going to attempt to retell what you already know here — all power is set alight by children. In U.S. politics we see a young Bill Clinton, who came from virtually nothing, rise to the highest office of the land but still has incredible struggles and failings with his moral compass. We see George W. Bush become president in spite of the odds set against him, particularly in that his former-president father George Herbert Walker Bush never thought he could do it. The continuance of the Bush political bloodline had always been bestowed upon brother Jeb Bush, but history had other plans. W. had a tragic side too, in this context, in having to prove himself worthy, by not just getting the presidency (something his parents wanted of Jeb) but in getting Saddam Hussein (something Bush Senior failed to accomplish in Desert Storm 1). Lots of set-ups, some to succeed, many to fail. Bush has to own the decisions he either made or consigned to powerful underlings like Donald Rumsfeld. There were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, but there was a slowly building fire. That fire burns today in the form of ISIS. Hard to say whether that first U.S. intervention caused such radical Islamic terrorism or just precipitated the inevitable incursion.

Aside from obvious touchpoints — so obvious that I’m not going to attempt to retell what you already know here — all power is set alight by children. In U.S. politics we see a young Bill Clinton, who came from virtually nothing, rise to the highest office of the land but still has incredible struggles and failings with his moral compass. We see George W. Bush become president in spite of the odds set against him, particularly in that his former-president father George Herbert Walker Bush never thought he could do it. The continuance of the Bush political bloodline had always been bestowed upon brother Jeb Bush, but history had other plans. W. had a tragic side too, in this context, in having to prove himself worthy, by not just getting the presidency (something his parents wanted of Jeb) but in getting Saddam Hussein (something Bush Senior failed to accomplish in Desert Storm 1). Lots of set-ups, some to succeed, many to fail. Bush has to own the decisions he either made or consigned to powerful underlings like Donald Rumsfeld. There were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, but there was a slowly building fire. That fire burns today in the form of ISIS. Hard to say whether that first U.S. intervention caused such radical Islamic terrorism or just precipitated the inevitable incursion.

Another child of a powerful man is former presidential candidate Willard (Mitt) Romney. His life seemed like a carbon copy of his father’s, George W. Romney, the Chairman and President of American Motors Corporation. Mitt succeeded in the takeover world with Bain Capital. George was governor of Michigan from 1963 to 1969. Mitt governed Massachusetts from 2002 to 2007. George ran for president and failed. If Mitt had succeeded, he would have broken free from dad’s formidable shadow, but he wound up mirroring his father in one more aspect. One wonders if that is why Mitt attempted to make nice with President-elect Donald Trump after the election. If he couldn’t be President, maybe being Secretary of State was grand enough. It was later stated that Trump only used these lunch discussions as a punishment to Romney for having defied him through the election cycle. The job is now aimed toward Chairman and CEO of ExxonMobil, Rex Tillerson.

Another child of a powerful man is former presidential candidate Willard (Mitt) Romney. His life seemed like a carbon copy of his father’s, George W. Romney, the Chairman and President of American Motors Corporation. Mitt succeeded in the takeover world with Bain Capital. George was governor of Michigan from 1963 to 1969. Mitt governed Massachusetts from 2002 to 2007. George ran for president and failed. If Mitt had succeeded, he would have broken free from dad’s formidable shadow, but he wound up mirroring his father in one more aspect. One wonders if that is why Mitt attempted to make nice with President-elect Donald Trump after the election. If he couldn’t be President, maybe being Secretary of State was grand enough. It was later stated that Trump only used these lunch discussions as a punishment to Romney for having defied him through the election cycle. The job is now aimed toward Chairman and CEO of ExxonMobil, Rex Tillerson.

Removing the arc of descent for the trajectories of these three men — Clinton, Bush, and Romney — each seemed to have something personal to gain, something to prove. And in spite of how they accomplished or didn’t accomplish their aims, they each seemed to want to achieve good things. They seemed to want to make things better. So it was with the fictional Charles Foster Kane and many factual people of power. Those who want to change the world for the better generally articulate those desires clearly, with some semblance of a pre-history to back them up. It’s the little child in the heart of every person — the one who feels disregarded and disrespected, abandoned or unloved — that seems to come out at the worst of times. They see those doors of opportunity opening to them and rather than think, “This is how I can achieve these things that will finally get that job done,” they think, “Now I will show them all,” or, “Now I’ll make them pay for leaving me behind,” or, “Now you will know you shouldn’t have walked away from me.”

Removing the arc of descent for the trajectories of these three men — Clinton, Bush, and Romney — each seemed to have something personal to gain, something to prove. And in spite of how they accomplished or didn’t accomplish their aims, they each seemed to want to achieve good things. They seemed to want to make things better. So it was with the fictional Charles Foster Kane and many factual people of power. Those who want to change the world for the better generally articulate those desires clearly, with some semblance of a pre-history to back them up. It’s the little child in the heart of every person — the one who feels disregarded and disrespected, abandoned or unloved — that seems to come out at the worst of times. They see those doors of opportunity opening to them and rather than think, “This is how I can achieve these things that will finally get that job done,” they think, “Now I will show them all,” or, “Now I’ll make them pay for leaving me behind,” or, “Now you will know you shouldn’t have walked away from me.”

I believe in the next seven years the resurgence of validity for Orson Welles’ enduring classic will be undeniable because it is a cautionary tale to the powerful. Why you do something is as important — maybe more important — than what you do. Intentions are important, and if your intentions are corrupt, then your politics will be corrupt, your relationships will be corrupt, and so will your art. The old saying about “absolute power corrupting absolutely” is only partially true. The other part is that in order to properly use what’s entrusted to you, you have to be able to grow up fully.

Heaven help those who willingly place power in the hands of angry children who only seek payback. Payback is a fire that destroys landscapes we’ll never be able to rebuild.

Comments