First world problems: the fictional universes we thought we knew have changed irrevocably. However, this wouldn’t have been the first time.

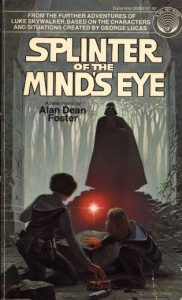

I recently pulled out a stack of old books. There was a trilogy of adventures featuring Han Solo by Brian Daley, a trilogy with Lando Calrissian by L. Neil Smith, and in particular, Splinter of the Mind’s Eye by Alan Dean Foster. Foster, a noted science fiction author, was also one of the preeminent movie novelization authors of the day. He was, in fact, the ghost writer of the novelization of Star Wars, which went out under George Lucas’ credited authorship. Foster is also the author of the recent novelization of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, bringing things full circle.

I recently pulled out a stack of old books. There was a trilogy of adventures featuring Han Solo by Brian Daley, a trilogy with Lando Calrissian by L. Neil Smith, and in particular, Splinter of the Mind’s Eye by Alan Dean Foster. Foster, a noted science fiction author, was also one of the preeminent movie novelization authors of the day. He was, in fact, the ghost writer of the novelization of Star Wars, which went out under George Lucas’ credited authorship. Foster is also the author of the recent novelization of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, bringing things full circle.

Splinter of the Mind’s Eye is an odd duck. The story concept was a fall-back position for Lucasfilm Ltd. There was always going to be a Star Wars sequel, unless the first movie did so incredibly badly that Lucas and crew would be run out of town on a rail. Splinter was the low-cost follow-up plot that did not need to happen as a script, thanks to the parent property’s overwhelming success, and was subsequently diverted to Foster’s hands and the burgeoning Star Wars merchandising juggernaut. As a one-off story it is a compact little adventure, made all wrong thanks to The Empire Strikes Back, which would arrive a few years later.

In Splinter, Darth Vader’s presence is far more antagonistic. Even though we were led to believe he tortured Princess Leia with a drug drone in that first movie, and would eventually chop off his son’s hand in the second, there was no consideration at that time that Vader would be fashioned to be the father to fraternal twins Luke Skywalker and Leia. He was more in the line of a Ming The Merciless, as was in the Flash Gordon serials; the stereotypical big baddie. So too, Luke and Leia’s relationship in Splinter is more romantic and, in light of the “official” continuation, far more skeevy. Fortunately, Empire was so far above expectations, it was easy to leave these tangents behind…even though, as examples of space opera fiction, they’re highly entertaining.

Who could have expected that this sort of narrative Alzheimer’s would be so prevalent and necessary by the time we reached the new millennium? Only recently, DC Comics (owned by Warner Media) announced they were moving to Hollywood away from their ominously-numbered longtime home, 666 Fifth Avenue in New York. With the move, the comics would receive yet another radical change, with the characters, look, and storylines hewing closer to the cinematic world DC was trying to build. Prior to the move, DC had attempted a revamp known as The New 52, taking their 52 most-prominent characters and hitting the reset button on them. They became more dark and brooding, or just plain off. Superman was turned into a part-emo/part-bro in an S-emblazoned t-shirt and jeans. This was just one of the deviations made to purportedly make these icons more relevant to their times. Problem is, most of these did not work.

Who could have expected that this sort of narrative Alzheimer’s would be so prevalent and necessary by the time we reached the new millennium? Only recently, DC Comics (owned by Warner Media) announced they were moving to Hollywood away from their ominously-numbered longtime home, 666 Fifth Avenue in New York. With the move, the comics would receive yet another radical change, with the characters, look, and storylines hewing closer to the cinematic world DC was trying to build. Prior to the move, DC had attempted a revamp known as The New 52, taking their 52 most-prominent characters and hitting the reset button on them. They became more dark and brooding, or just plain off. Superman was turned into a part-emo/part-bro in an S-emblazoned t-shirt and jeans. This was just one of the deviations made to purportedly make these icons more relevant to their times. Problem is, most of these did not work.

Sweeping changes are not a new thing. But dealing with what is left behind, on the other hand, is because up to this point there has seldom been a declaration that this now is THE story and all the rest are just slightly above the level of fan-fiction, harmless, but inessential in every way.

Two things have created this schism: synergy and memory. We’ll start with the latter.

Synergy and Memory: When Splinter of the Mind’s Eye came out in the late-1970s there was no such thing as home video and maybe you would get to see a movie again when it was run in edited form on television. These used to be big events before cable television made endlessly-rerun films commonplace. If you wanted to relive a movie’s story, you did it through books, comics, or memory. Otherwise, you accepted it as you remembered it and picked up on it again if a sequel was made or if it was turned into a TV show (like Planet of the Apes or Logan’s Run). There was nothing to reinforce the fine points of a narrative in the collective consciousness.

Synergy and Memory: When Splinter of the Mind’s Eye came out in the late-1970s there was no such thing as home video and maybe you would get to see a movie again when it was run in edited form on television. These used to be big events before cable television made endlessly-rerun films commonplace. If you wanted to relive a movie’s story, you did it through books, comics, or memory. Otherwise, you accepted it as you remembered it and picked up on it again if a sequel was made or if it was turned into a TV show (like Planet of the Apes or Logan’s Run). There was nothing to reinforce the fine points of a narrative in the collective consciousness.

And even with television, there’s a lousy track record of continuity. In nearly every season of TV’s version of Neil Simon’s The Odd Couple, Oscar Madison and Felix Unger recount completely different ways in regard to how they met. Syndicated rebroadcasting would allude to the weirdness of the ever-changing past, but what cemented the incongruity was the video cassette recorder, and later the home video industry. You wouldn’t have to remember the small details of a movie or a TV show. It was there, waiting on a book shelf. All you had to do was stick the tape into the machine and watch it.

With that kind of verifiable certainty at everyone’s fingertips, a need to be more precise fell into favor. No longer could Batman the comic book be a little harder-edged while the show was goofy camp. They had to sync up somehow.

That’s where synergy comes in. I’ve no need to recount how George Lucas’ fortunes were built not by the movies he made but by the licenses for the merchandising the movies spawned. By the end of the Eighties and into the 1990s, the dual realities of movies and TV versus ancillary media were becoming harder to maintain. Marvel was, at that time and very briefly, owned by Roger Corman’s New World Pictures. Attempts were made to bring the characters to the big screen; all were unsuccessful and some were terribly embarrassing. It was felt that, in some of these cases, the movies might do serious harm to the brands.

That’s where synergy comes in. I’ve no need to recount how George Lucas’ fortunes were built not by the movies he made but by the licenses for the merchandising the movies spawned. By the end of the Eighties and into the 1990s, the dual realities of movies and TV versus ancillary media were becoming harder to maintain. Marvel was, at that time and very briefly, owned by Roger Corman’s New World Pictures. Attempts were made to bring the characters to the big screen; all were unsuccessful and some were terribly embarrassing. It was felt that, in some of these cases, the movies might do serious harm to the brands.

It wasn’t until later in the ’90s when the X-Men, a 20th Century Fox production, debuted on the big screen that the curse that bedeviled Marvel’s desire to break out seemed to lift. This eventually led to Marvel’s grand scheme to forge the Marvel Cinematic Universe, initially as a partnership between them, Paramount Pictures, and Disney. Disney is key here, as the Mouse House is the undisputed master of cross-platform synergy. They not only link their television presence to their cinematic presence and to their print and toy presence (never mind their theme parks), but they cross-breed the classifications within properties. The Disney Princesses is a superteam that exists solely in the company’s implications, and the inferences of the girls that love them, but is as powerful as any concrete collective. Under Disney, Marvel started to get very, very serious about alignment, and that was the beginning for almost all of them.

All That Other Stuff: But that leaves behind decades of stuff that no longer applies. Almost the entire 1960s — when Batman and Robin were groovy and chasing down cartoonish dolts, not true sociopaths — was jeopardized when Frank Miller created DC’s The Dark Knight Returns. Tim Burton made that the foundation of his darker (but still slightly broad) version of Batman. The syndicated cartoon series was literally painted on backdrops of black. After some filmic lapses back into candy-colored camp (under maligned director Joel Schumacher), most of which didn’t jibe with the comics’ angst-ridden sensibilities and subsequently failed, Christopher Nolan plunged the character into night for good with his trilogy. What to do with the Val Kilmer and George Clooney Batmen? What about the Adam West Batman? These were real things until, after the brand management conference, they weren’t.

All That Other Stuff: But that leaves behind decades of stuff that no longer applies. Almost the entire 1960s — when Batman and Robin were groovy and chasing down cartoonish dolts, not true sociopaths — was jeopardized when Frank Miller created DC’s The Dark Knight Returns. Tim Burton made that the foundation of his darker (but still slightly broad) version of Batman. The syndicated cartoon series was literally painted on backdrops of black. After some filmic lapses back into candy-colored camp (under maligned director Joel Schumacher), most of which didn’t jibe with the comics’ angst-ridden sensibilities and subsequently failed, Christopher Nolan plunged the character into night for good with his trilogy. What to do with the Val Kilmer and George Clooney Batmen? What about the Adam West Batman? These were real things until, after the brand management conference, they weren’t.

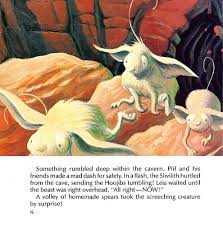

Marvel’s initial run of Star Wars comics, aside from movie adaptations, have no bearing on the continuity, Hoojibs be damned. Neither does the long run created at Dark Horse Comics, and the beloved Timothy Zahn trilogy of novels featuring Admiral Thrawn? A fever dream. For the collector of all this paraphernalia who thought this stuff was going to buy them a cushy retirement one day, it’s a nightmare. Who’s going to want all this irrelevant stuff 20 years from now when the series are still going on, leaving the old standalone stories behind?

Marvel’s initial run of Star Wars comics, aside from movie adaptations, have no bearing on the continuity, Hoojibs be damned. Neither does the long run created at Dark Horse Comics, and the beloved Timothy Zahn trilogy of novels featuring Admiral Thrawn? A fever dream. For the collector of all this paraphernalia who thought this stuff was going to buy them a cushy retirement one day, it’s a nightmare. Who’s going to want all this irrelevant stuff 20 years from now when the series are still going on, leaving the old standalone stories behind?

For the actual fans, we will have clear generational disparities, and points where an individual will have to decide if they’re still on board or not. The George Reeves version of Superman was not totally different from the Christopher Reeve rendition. The Tom Welling, Gerard Christopher, and Dean Cain versions a little less so. The Henry Cavill version is far different, and is set to become the template for what Superman is — in all areas — going forward. It will be the fans’ decision to stay on that course or jump off at the next station.

That’s the question: what do we do with all this non-canonical media when it is no longer supported by the corporation? Just as individuals are required to make choices about computer and phone operating systems when new versions come down, or risk hanging onto old versions knowing that those OS-es could go obsolete at any time, so too will they have to decide what generation of a character they want to stay with. Those who ride along with Cavill and Ben Affleck as Batman will likely have a very long run. Those who still think Michael Keaton was the best Batman have to be content with the character in a self-contained narrative snowglobe, detached from future interactions or iterations.

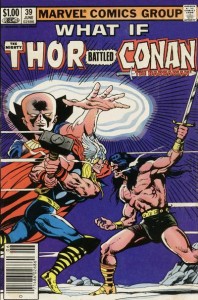

In the end, maybe Marvel had it right all along. One of my favorite comics as a kid was the What If? series where the writers and artists placed characters in alternate scenarios, apart from the supposed canonical narrative — What if Jean Grey hadn’t become Dark Phoenix? What if Dr. Doom was a hero? What if Spider Man saved Gwen Stacy? In essence, all these media companies are taking an active gamble. The foundations upon which they’ve been built will now be relegated to these flights of fancy. Nearly a century of myth making will be an elaborate series of What Ifs, disconnected and discontinued. They can all still be entertaining and are far from a waste of your time, but you the consumer do have to make that choice. Do you invest the time in these stories of the past, even if they are just as much daydreams?

In the end, maybe Marvel had it right all along. One of my favorite comics as a kid was the What If? series where the writers and artists placed characters in alternate scenarios, apart from the supposed canonical narrative — What if Jean Grey hadn’t become Dark Phoenix? What if Dr. Doom was a hero? What if Spider Man saved Gwen Stacy? In essence, all these media companies are taking an active gamble. The foundations upon which they’ve been built will now be relegated to these flights of fancy. Nearly a century of myth making will be an elaborate series of What Ifs, disconnected and discontinued. They can all still be entertaining and are far from a waste of your time, but you the consumer do have to make that choice. Do you invest the time in these stories of the past, even if they are just as much daydreams?

Comments