Welcome to Halloween 2022, a perfect day to discuss the resurrection of a particularly troublesome argument skulking around the pop culture zeitgeist, specifically within the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). There’s a two-pronged impetus for my examination: the recasting of Harrison Ford in the role of General “Thunderbolt” Ross following the death of actor William Hurt, and not recasting the role of T’Challa, also known as the superhero Black Panther, memorably portrayed by Chadwick Boseman. The sequel, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, arrives in theaters only a few days from now.

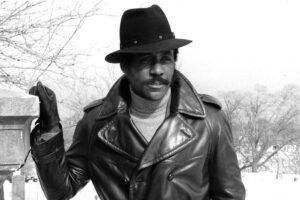

Before we discuss why I feel Marvel made the right decision with T’Challa, I think it is important to talk about the comic book landscape from which the character came. To say most of it was misguided is giving it too much credit, and it wasn’t sequestered to just Marvel or crosstown rival DC either. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, character creation was reactionary, built upon trends more than anything else. This is why you get a character like the Silver Surfer, a tragic figure made a servant of a malevolent god-like figure that eats planets, racing before him through space to future victims…on a surfboard. Characters like Black Panther arose from the Black Power movement of the late 60s, with characters like Power Man/Luke Cage arriving a little later, informed by so-called Blaxploitation cinema like Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s BaadAsssss Song, the Dolemite films, and most importantly, Shaft. Notably, these films arrived as a form of satire, created by African American filmmakers with a tongue-in-cheek aesthetic. As noted by musician/actor Isaac Hayes in an interview on NPR’s Fresh Air program, “We weren’t taking ourselves seriously, not as the characters…we were glad to have the work, glad to have our people see us onscreen, and (not in the stereotypical fashion) of bowing and saying ‘yassir, boss’.”

The issue was with the translation. While the Blaxploitation films were often the domain of black creators, the comics mostly were not. Therefore, a lot of the worst examples weren’t authentic to the African American experience and/or did not get the intention, but instead were a broad version of it made even broader by older, white creators. This is where you end up with a lot of characters leaning into the language of going up against “jive talkin’ turkeys” and “honkies,” through a one-sided game of cultural telephone.

The issue was with the translation. While the Blaxploitation films were often the domain of black creators, the comics mostly were not. Therefore, a lot of the worst examples weren’t authentic to the African American experience and/or did not get the intention, but instead were a broad version of it made even broader by older, white creators. This is where you end up with a lot of characters leaning into the language of going up against “jive talkin’ turkeys” and “honkies,” through a one-sided game of cultural telephone.

Over the years, you’d see black superheros get some spotlight, but there was always that hint of afterthought, certainly nothing as definitive as Christopher Reeve’s portrayal of Superman. Some might say Christian Bale’s Batman ranks equally high. Yes, they both have been recast. In fact, DC can’t seem to STOP recasting Batman, but that’s an argument for another rant. It is that for a long time, it felt wrong to recast those roles. While I appreciated the Michael Keaton version of Batman greatly, the two films with him were over and done so quickly that when Val Kilmer and George Clooney succeeded him, it felt less like undoing a cultural moment and more like business as usual.

Harrison Ford replacing William Hurt also feels like business as usual. Not good or bad, merely expected.

Chadwick Boseman as T’Challa is different. For once, a fully-realized character of dignity and real gravity came from the Marvel Comics pantheon without compromise. Brought to the screen by director Ryan Coogler, and if my information is correct, rendered by Boseman knowing this was likely one of, if not his final, performances, Black Panther is a film that ranks in characterization with Reeve’s Superman. Maybe the CGI in the film is a tad janky – I can’t deny that. But in delineating Wakanda as a utopia where its citizens live at the highest levels, and in giving T’Challa’s depiction such a focused and committed performance, the two seem inseparable. It seems wrong to try.

Hollywood doesn’t make movies to make nice. It makes movies to make money. Thus, there was only the strongest belief that T’Challa would be recast and the dollar-printing mechanism would roll on unimpeded. Marvel took a different path and said, “No,” at least for now. (Who knows what all this multiverse nonsense will bring.) Frankly, I love this decision.

Hollywood doesn’t make movies to make nice. It makes movies to make money. Thus, there was only the strongest belief that T’Challa would be recast and the dollar-printing mechanism would roll on unimpeded. Marvel took a different path and said, “No,” at least for now. (Who knows what all this multiverse nonsense will bring.) Frankly, I love this decision.

I cannot speak for African Americans and would be stupid to try. In my meager, mostly anonymous role on this planet, I still cannot ignore the many privileges I’ve been born with. I can only speak to the side of things I do know.

I preface this by saying that I love my older relatives and miss them dearly every day. But I can’t ignore that they lived primarily in all-white communities and frequently spoke with that insular mindset. For anyone other than their specific physicality, it was a similar phrase I heard a lot, and I bet you heard it a lot, too. “They all look alike to me.” If a white actor replaced another white actor in a role, typically on a daytime soap opera, there might be a learning curve, a time of getting used to the new guy. But there was hardly a peep when one Lionel Jefferson was suddenly a new Lionel Jefferson, or one Gordon was another Gordon on Sesame Street. The opinion of African American interchangeability was rampant in the 1970s and persisted into the 1980s. Given that I am talking about my lost and loved elders, it bothers me to say it, but it’s true. It was racism.

I preface this by saying that I love my older relatives and miss them dearly every day. But I can’t ignore that they lived primarily in all-white communities and frequently spoke with that insular mindset. For anyone other than their specific physicality, it was a similar phrase I heard a lot, and I bet you heard it a lot, too. “They all look alike to me.” If a white actor replaced another white actor in a role, typically on a daytime soap opera, there might be a learning curve, a time of getting used to the new guy. But there was hardly a peep when one Lionel Jefferson was suddenly a new Lionel Jefferson, or one Gordon was another Gordon on Sesame Street. The opinion of African American interchangeability was rampant in the 1970s and persisted into the 1980s. Given that I am talking about my lost and loved elders, it bothers me to say it, but it’s true. It was racism.

That’s part of why I think people will be moved when they see Wakanda Forever. It doesn’t gloss over Chadwick Boseman’s absence but instead makes this the inciting action that drives the story forward. It’s not a thing to get over – it is THE THING. It states that while Black Panther will move on, T’Challa is irreplaceable. It is a courageous decision on Marvel’s part, even while it seems to play it safe in every other property.

I’m not sure why I am as affected by this as I am, even as other pundits spew thinkpieces galore on why T’Challa should have been recast. I guess it strikes me as progress.

Comments