I had planned to write about Lazarus, David Bowie’s “music theater” concoction, last month, when I saw it Off Broadway. Then I decided to combine it with a review of the Broadway revival of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge, also directed by theatrical wunderkind Ivo van Hove. Then there were numerous movies to review. Christmas, New Year’s, and travel. Lazarus‘ all but sold-out run ends Jan. 20, I mused. It can wait.

I had planned to write about Lazarus, David Bowie’s “music theater” concoction, last month, when I saw it Off Broadway. Then I decided to combine it with a review of the Broadway revival of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge, also directed by theatrical wunderkind Ivo van Hove. Then there were numerous movies to review. Christmas, New Year’s, and travel. Lazarus‘ all but sold-out run ends Jan. 20, I mused. It can wait.

Then Bowie died.

I was stunned. First by sadness–then by the utter perfection of his passing. A master of marketing, with unparalleled command of the dramatis personae of his art, had conquered death, made it work for him. Lazarus uses material from Blackstar, his last album, which we now know was a “parting gift” for us, generously released on what would be his last birthday. As commemoration entwines with commerce and the record races up the charts, the show fulfills its function as part of a multimedia project devoted to his departure.

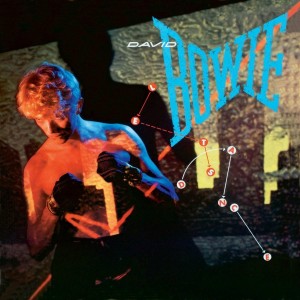

Fleetingly fulfills, that is. I wasn’t all that cognizant of Bowie until the zenith of his “accessible” phase, the megahit 1983 album Let’s Dance, with its smash MTV videos. I saw Bowie more than I listened to him, including his strikingly composed performance in that year’s chic horror film The Hunger. (Would we ever have gotten the “old Bowie” as seen in the movie, as age finally catches up with his vampire?) The one time I saw him onstage was during the Chicago leg of the Glass Spider Tour in 1987, which, with its clunky, overbearing production, was a disappointment, one that reduced him to feature player status. (An influential disappointment, but still.) 1986’s fantasy flop Labyrinth also obscured him with frippery. After that phase, I don’t think the handsomest of enigmas ceded his image to scene-stealing makeovers ever again. He was his own best special effect, as he demonstrated on Broadway in The Elephant Man, minus makeup.

Fleetingly fulfills, that is. I wasn’t all that cognizant of Bowie until the zenith of his “accessible” phase, the megahit 1983 album Let’s Dance, with its smash MTV videos. I saw Bowie more than I listened to him, including his strikingly composed performance in that year’s chic horror film The Hunger. (Would we ever have gotten the “old Bowie” as seen in the movie, as age finally catches up with his vampire?) The one time I saw him onstage was during the Chicago leg of the Glass Spider Tour in 1987, which, with its clunky, overbearing production, was a disappointment, one that reduced him to feature player status. (An influential disappointment, but still.) 1986’s fantasy flop Labyrinth also obscured him with frippery. After that phase, I don’t think the handsomest of enigmas ceded his image to scene-stealing makeovers ever again. He was his own best special effect, as he demonstrated on Broadway in The Elephant Man, minus makeup.

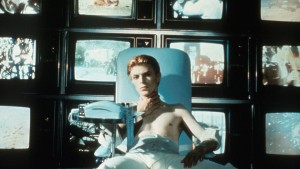

Downtown, Lazarus continues his brand of maxi-minimalism. “Music theater” is the hipper term for “jukebox musical,” which the show is, as well as a movie into musical, or a musical heavily influenced by a movie. Lazarus uses Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), showcasing Bowie’s starring debut, as its inspiration. It begins with Thomas Jerome Newton, gin-soaked in his apartment, aimlessly flipping through TV channels, depicted by the projections that define what is largely a white-and-beige space of an apartment. Newton, a paranoid billionaire, made his fortune in his doomed attempt to return to his water-deprived planet, not that the show is all that explicit about his extraterrestrial origins. It’s not that explicit about anything, really, and if you don’t know the film, or its source novel, you’re likely to meander through Lazarus, lost.

Downtown, Lazarus continues his brand of maxi-minimalism. “Music theater” is the hipper term for “jukebox musical,” which the show is, as well as a movie into musical, or a musical heavily influenced by a movie. Lazarus uses Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), showcasing Bowie’s starring debut, as its inspiration. It begins with Thomas Jerome Newton, gin-soaked in his apartment, aimlessly flipping through TV channels, depicted by the projections that define what is largely a white-and-beige space of an apartment. Newton, a paranoid billionaire, made his fortune in his doomed attempt to return to his water-deprived planet, not that the show is all that explicit about his extraterrestrial origins. It’s not that explicit about anything, really, and if you don’t know the film, or its source novel, you’re likely to meander through Lazarus, lost.

That may not be the worst thing. While trying to parse the changes to Roeg’s already elliptical (but wholly engrossing) masterpiece, the rest of the narrative, the story that seemed to be in there somewhere, kept slipping away. Lazarus is about poses, images, stage pictures–milk and blood are spilled, balloons are kicked around, teenage groupies and Kabuki-masked phantasms loll about, outlines of rocketships are drawn, and, oh, there’s Alan Cumming, or rather, a projection of Alan Cumming, who has some sort of vague connection to the idealized girl of Newton’s dreams. Two hours, no intermission, and if you’re in the middle of one of New York Theatre Workshop’s long rows of seats, you’re trapped.

Lazarus most reminded me of the elephantine Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, another example of rock and theater artists getting together to put on a show, not coming up with much of interest to put on, then putting it on anyway. Bowie, van Hove, and co-writer Enda Walsh (who won a Tony for his book for the musical of the movie Once) had ideas, some of them lousy. (The balloon thing? Done. To death.) The surprise of Lazarus is how unsurprising it is–nonsensical plot aside (why not just a musical adaptation of the source material?), the avant garde touches are mosty pretty hokey. The director’s NYTW adaptation of The Misanthrope concluded with the actors running into the street and performing the last scene outdoors; Lazarus concludes with the audience running into the street, fleeing the wasted evening. The day reviews appeared, those once-hot tickets started appearing online, for sale.

Lazarus most reminded me of the elephantine Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, another example of rock and theater artists getting together to put on a show, not coming up with much of interest to put on, then putting it on anyway. Bowie, van Hove, and co-writer Enda Walsh (who won a Tony for his book for the musical of the movie Once) had ideas, some of them lousy. (The balloon thing? Done. To death.) The surprise of Lazarus is how unsurprising it is–nonsensical plot aside (why not just a musical adaptation of the source material?), the avant garde touches are mosty pretty hokey. The director’s NYTW adaptation of The Misanthrope concluded with the actors running into the street and performing the last scene outdoors; Lazarus concludes with the audience running into the street, fleeing the wasted evening. The day reviews appeared, those once-hot tickets started appearing online, for sale.

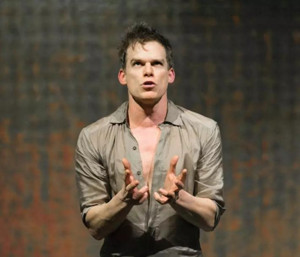

That won’t be the case now. You’re still not getting much of a show, particularly if you’re paying upwards of $1,300 a seat, the going scalped rate as of Monday. Then again you’re not getting Lazarus anymore–you’re getting a final statement from its creative wellspring, imperfectly conceived as it is. The Bowie records and turntable onstage attest to his full genius. As does–the show’s saving grace–his music, played by an onstage orchestra neatly glassed in behind the performers, and interestingly selected. (I didn’t think “Absolute Beginners” or “This is Not America,” from 1985’s The Falcon and the Snowman, could be repurposed, but here they are.) Dropping their limp characterizations, stage veterans Cristin Milioti (from Once, and TV’s Fargo and How I Met Your Mother) and Michael Esper (playing a villain of some sort) offer appealing interpretations of standards like “Changes,” and then there’s star Michael C. Hall. Onstage, Dexter brought an androgynous excitement to Cabaret and Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and when not playing the fogged-in Newton he cuts loose in concert-stylednumbers and “does” Bowie to perfection. As news of Bowie’s death circulated, the performers gathered to record the cast album. Lazarus will live again, in its best and purest form.

Comments