I spent most of the 1990s training myself to be a self-conscious aesthete. Which makes me sound, I suppose, like some horrible, sneering, holier-than-thou funwrecker. Really, though, it was just a necessary element of my education. My life is (like most lives, I imagine) a long project of self-improvement; so for a while I undertook a deliberate study of the arts, spent some time formulating and investigating a set of provisional opinions about them, and did some serious thinking about the creative process — especially my creative process. This is the whole reason why I stand before you now as a writer and a critic.

I spent most of the 1990s training myself to be a self-conscious aesthete. Which makes me sound, I suppose, like some horrible, sneering, holier-than-thou funwrecker. Really, though, it was just a necessary element of my education. My life is (like most lives, I imagine) a long project of self-improvement; so for a while I undertook a deliberate study of the arts, spent some time formulating and investigating a set of provisional opinions about them, and did some serious thinking about the creative process — especially my creative process. This is the whole reason why I stand before you now as a writer and a critic.

There were two books in particular that blew my mind. The first was Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics — for my money the most important American book about the arts published in the last twenty years — and a little hardback called Surrealist Games that I picked up at a museum gift shop. It’s an odd pairing, on the face of it. McCloud is comics’ preeminent formalist, thinking hard about every aspect of the craft, from the width of the individual line to the relative gap between two panels, in how it contributes to the overall effect. The Surrealists, by contrast, strove to remove the rational mind from the creative equation altogether. Taking the model of art as game, with arbitrary rules or random elements providing a framework for free play — just as the chord changes of a jazz standard anchor the improvisation — they strove to tap into a purer form of expression, unmediated by convention, training, or good taste. It was (though the Surrealists, atheists in the main, would probably reject the term) a mystical model, aiming for direct experience of the divine creative spark.

So. The leading theoretician of his medium vs. the rudely anti-theoretical malcontents of theirs. Surely there could be no common ground here.

Except that there was.

Somewhere along the line I heard about McCloud’s 24-hour comics challenge — it must have been in print somewhere, in those pre-Internet days. It’s a terribly simple idea: produce 24 finished pages of comics — written, drawn, and lettered — in a single day. Twenty-four pages of sequential art, telling a complete story, completed in as many sequential hours, with no significant preparation; just sit down at the blank page at Hour One, and go for it. Spontaneous creation on a par with the Surrealists’ automatic writing.

Somewhere along the line I heard about McCloud’s 24-hour comics challenge — it must have been in print somewhere, in those pre-Internet days. It’s a terribly simple idea: produce 24 finished pages of comics — written, drawn, and lettered — in a single day. Twenty-four pages of sequential art, telling a complete story, completed in as many sequential hours, with no significant preparation; just sit down at the blank page at Hour One, and go for it. Spontaneous creation on a par with the Surrealists’ automatic writing.

The idea appealed to me immediately. Like NaNoWriMo, the 24HC uses a hard deadline to spur creativity; for most of us, it’s the closest we’ll ever come to being forced to make art at gunpoint. And I liked the unreasonable stay-up-all-night requirement. Sleeplessness is something of a mystical state itself, and very much in keeping with the Surrealist methods of (to steal a phrase from the forefather Rimbaud) ”deliberate derangement of the senses.” Best of all, the fact that I can’t draw for beans was (from a Surrealist point of view, anyway) a bonus, since anything I produced was unlikely to be contaminated by ”proper” technique.

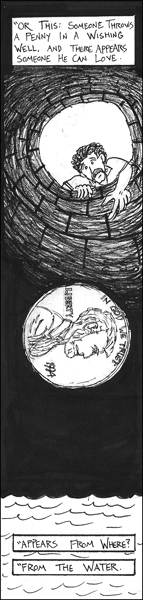

And so on June 25, 1993, I sat down with a stack of Bristol board, a pile of freshly-sharpened pencils, and a single phrase that had been rolling around my skull for days — An artist thrown into deep water will always find his own way to get by. And, after a couple of lengthy false starts, I made comics until I physically collapsed, 21 hours in, with my 24-page story complete except for a few pages yet to be inked.

I made two more attempts at the 24-hour comic challenge over the next year, and never completed the requirements in the time allotted; but I completed 72 pages of comics, telling a full story — a story that surprised and excited me, that came from strange and unexpected places, full of obscure images and symbols that simply felt right. And in each case, the conceptual work, the skeleton of the thing, was knocked together in the initial all-nighter. Fatigue and pressure kickstarted the ideas, which came with an ease and speed I had never known before.

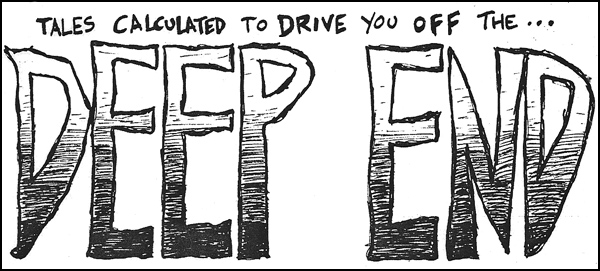

And then I was done, and the story was complete. Picking up on the water imagery running through the whole, I slapped it with an EC-inspired title…

I had music playing the whole time I was working. I didn’t have the School of Fish record at the time, although it had come out a couple of years before — twenty years ago today, as I write this, in fact; I had heard it, though, at a friend’s place. I remembered liking the single ”Three Strange Days,” and took a verse from it as the epigram for the final volume:

I lay down for a while

And I woke up on the ocean

Floating on my back and staring at the grey

It was completely still

Except the pounding of my heart

Bringing me back to life from three strange days…

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/onjaC3A2xjk" width="600" height="458" allowfullscreen="true" fvars="fs=1" /]

Now, gearshift key change and all, there’s a lot to like there, right? Crunching rhythm guitars, blazing fills, and the kind of melody that invites you not just to sing along but to add your own harmonies. Smart, catchy stuff.

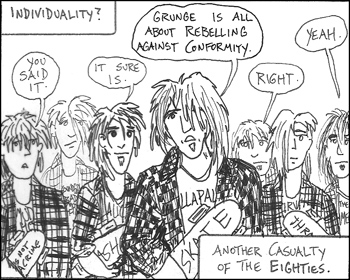

School of Fish, a.k.a. singer-guitarist Josh Clayton-Felt and guitar wiz Mike Ward, were a couple of kids with a nice batch of songs, knocking around L.A. as a two-piece, playing to canned rhythm tracks, when they were snatched up in the Great Alternative Signing Frenzy at the turn of the decade. Now, 1991 was a curious time for the music business. After Joshua Tree but before grunge, post-Duran Duran but pre-boy band, a new decade seemed to call for a new sound. With synth-pop and hair metal alike seeming increasingly played-out, the labels were (as always) looking for the Next Big Thing. Some folks put their money on a resurgence of power-pop; history, of course, tells us that they were backing the wrong horse, commercially — but it did make for some great records.

What I really liked about School of Fish was their youth and promise. They were right about my age, in fact, and I dug their air of being a work in progress. (I could relate.) With their breakup after 1994’s Human Cannonball, followed by Josh Clayton-Felt’s untimely death of cancer in 2000, they never reached their potential; but School of Fish’s output sounds like a document of their creative process, laid down with a rare transparency—a process whose principles apply as well to making an album as to making a comic.

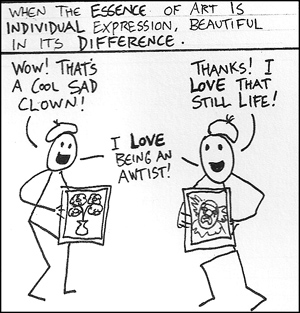

Embrace your limitations. I’m not an artist, not really; my art will never be more than functional. I have the gift, however, to be a storyteller, and the exceptionally rare good fortune to know that I am a storyteller — which is why my comics projects leaned on the words to do the heavy lifting, and also why I am telling you a story right now.

And School of Fish? It’s a guitar record, pure and simple. The vocals aren’t fussy — while there are a few overdubbed harmonies here and there, we’re plainly not dealing with Enya here — and the drum programming sounds stiff and crude, even for 1991. The guitar is the main tool here, and School of Fish make the most of it. After the band’s breakup, Ward had a long career ahead of him as a session guitarist, and that’s a job less dependent on flash or chops (though he has both) than on a keen ear for tones. Here, he and Clayton-Felt use the studio to create a distinct sonic identity for each song. Sitars double sizzling Ebow lines behind sparkling layers of twelve-string acoustics; twanging tremolo licks dissolve into grinding mechanical noise; feedback conjures the roar of ocean waves. In a sense, the approach is a throwback to producer John Porter’s work with the Smiths, with whom he often also set a dense wall of guitars against boxy programmed rhythms. But in the end it succeeds due to the care and imagination lavished on the guitar sounds.

Play with your influences. Every artist has em, and we are interesting as artists primarily in how we process our influences. We may embrace them, presenting ourselves as squarely in a shared tradition; or we may define ourselves by opposition, reclamation, deconstruction. The Deep End comics wound up being a reflexive work, a story about stories, and the influences I had in mind while making them included Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun, Isak Dinesen, Paul Bowles, Meatball Fulton’s audio dramas, Joseph Conrad, T.S. Eliot, Yeats, and Dylan Thomas. It’s all in there, if you know where to look, but the very flavor of the mash-up — its components, its elements, the conscious riffing — comes out reading like me.

Play with your influences. Every artist has em, and we are interesting as artists primarily in how we process our influences. We may embrace them, presenting ourselves as squarely in a shared tradition; or we may define ourselves by opposition, reclamation, deconstruction. The Deep End comics wound up being a reflexive work, a story about stories, and the influences I had in mind while making them included Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun, Isak Dinesen, Paul Bowles, Meatball Fulton’s audio dramas, Joseph Conrad, T.S. Eliot, Yeats, and Dylan Thomas. It’s all in there, if you know where to look, but the very flavor of the mash-up — its components, its elements, the conscious riffing — comes out reading like me.

School of Fish had obvious precedents in the power-pop scene, but owned and homaged their influences with wit and dash. As studio rats, they owed a clear debt to Prince, and their cover of ”Let’s Pretend We’re Married” (released as a non-LP b-side) pays in full. Their own ”King of the Dollar” cheekily quotes the riff from ”Satisfaction” before crashing into a radiant, Beatlesque chorus — encapsulating the inescapability of rock n’ roll tradition. And Clayton-Felt’s high, keening voice vaguely recalls the Replacements’ Paul Westerberg minus ten thousand cigarettes, with lyrics likewise capable of both yearning and snottiness.

Only connect. The combination of a hard deadline, no pre-writing, and a page requirement necessitates a yoking-together of ideas for a 24-hour comic project. I was following my ideas from vignette to vignette, tying them together as best I could on the fly, and as I did so the superstructure gradually revealed itself.

School of Fish, meticulously assembled in the studio, is anything but a spontaneous act of creation. But it does kick off with a series of songs that blend into each other. This was something of a trend, at the time — a reaction, I think, to the gapless segues and instant track-access of the CD format, perhaps in nostalgia for the unified listening experience of the LP era — but for School of Fish it serves a purpose; the suite takes the edge off the highly-artificed nature of the songs, and by imposing the illusion of flow it helps the record to seem warm and organic.

Know when to give it up and go to bed. Okay, maybe this one is mostly for me. But it’s worth noting that after the first four tracks, the songs stop segueing into one another; the record has made its point.

Don’t be afraid to be several things at once. The format of Deep End allowed me to make a narrative without being bound by the usual rules. The episodic structure left me the freedom for pastiche, bad jokes, opinions and asides. At various points it is a travelogue, a creation myth, a hero’s journey, and a cracked love story, with a sort of dream-logic holding it together.

School of Fish, likewise, finds room to be several different kinds of band here; the blissed-out mantras of ”Intro” both introduce and counterpoint the absurd tribulations of ”Three Strange Days.” The aforementioned ”King of the Dollar” is a character sketch. ”Under the Microscope” and the closing ”Euphoria” blend atmosphere and story, while ”Rose Colored Glasses” and ”Speechless” are more introspective.

The band switches up the sound throughout, never more strikingly than on ”Fell” (download), where they adopt a live, folky feel. It’s the most Westerbergian track here — sweet, sad, and beautifully-observed.

Take your synchronicities where you find them. I was talking a little bit above about how hidden narrative threads can reveal themselves. That happens when seemingly unrelated events or images demonstrate an unexpected connection. It happens all the time in art. That’s one of the things that delighted the Surrealists, and the concept of synchronicity formed the basis of one of their best-loved parlor games, ”One Into the Other.”

The game — the objective of which was to describe one object in terms of another, such that the other players could guess its identity — was invented by AndrÁ© Breton, beginning with the poetic observation that a lit match could be, for poetic purposes, a lion; the flame corresponding to the mane, the scratch against the striker the growl. ”The lion is in the match,” insisted Breton, ”just as the match is in the lion.” In another round of the game, the secret word was sword, to be described in the terms of a necktie: ”I am a gleaming necktie knotted around the hand so as to run across those throats at which I am placed.” Breton notes, in his reminiscences, that the game was played hundreds of times, and never, not once, did a player fail to find a correspondence between the two objects, no matter how random and seemingly dissimilar they were.

Never. Not even once.

Before I started writing this article, I had not listened to School of Fish in its entirety in many years, if ever. I chose to write about it based solely on fond memories of ”Three Strange Days.” And I knew that I wanted to mention Tales Calculated to Drive You Off the Deep End, if only in passing. But those hidden threads of synchronicity had other plans.

I had loaded the album on my iPod to listen while I walked the dog, and I was stopped in my tracks when I landed on a track I couldn’t recall ever hearing before — a track called ”Deep End” (download). It’s School of Fish at their most cinematic, an ocean of guitars whooshing and booming like the Pacific, and it sounded like what it says — an invitation to be overwhelmed.

And I was. I stood there in the snow, overcome with delight, with wonder, with an aching sadness that I could not define. And, most of all, with gratitude — to Mike Ward, to the ghost of Josh Clayton-Felt, and mostly to the insufferable poseur that I was twenty years ago (a former self who is also, in his way, a ghost) who was working so hard to develop sensitivity and sensibility; grateful and privileged to find myself still able to be surprised by beauty.

Comments