Isaac Asimov reportedly once said, “There is no belief, however foolish, that will not gather its faithful adherents who will defend it to the death,” and I dare say that everyone who’s reading this piece…oh, hell, I think we’re safe in expanding it to anyone who visits this site…has an album or two within their collection that would fall under the blanket of this theory: no one else loves it, but you do, and you’ll gladly offer up a half dozen reasons why they’re wrong and you’re right.

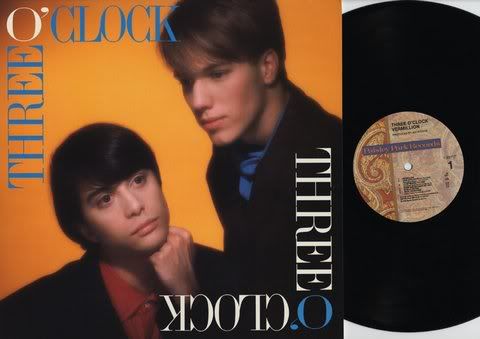

I’d love to tell you that the Three O’Clock’s final album, Vermillion, is one of those albums for me, but while there’s no question that I love it, I can’t do a whole lot to defend it. Mind you, I say that mostly because the sort of people with whom I’d be likely to enter into a debate on the album’s quality are well familiar with the band’s complete oeuvre, and, personally, I can’t imagine any Three O’Clock fan who’d be willing to go out on the limb labeled ”Vermillion is the Best Thing Those Guys Ever Did.” With that said, however, I still love the record and spin it all the time…which, of course, is why it’s earning a spot in the ”Hooks N’ You” spotlight.

I first fell into the music of The Three O’Clock by reading a review of their 1985 I.R.S. Records debut, Arrive Without Traveling, in a back issue of Rolling Stone. I promptly bought a copy on cassette (this would’ve been 1987, I believe, so I didn’t have a CD player and rarely used my turntable), only to have it stolen out of my car just as I’d started to fall in love with it, and when I went to replace it, the store didn’t have any other copies. D’oh! I never got around to replacing it – I’d dived headlong into alternate music, and there were just too many bands out there that I hadn’t yet explored – but I wouldn’t forget about The Three O’Clock. When I took a job at Record Bar, one of the first CDs I special-ordered was the band’s 1986 album, Ever After (now, ironically, available on a 2-fer CD with Arrive Without Traveling), and a bit after that, I finally found myself a copy of Sixteen Tambourines and truly had my mind blown.

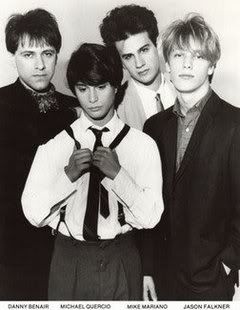

Unfortunately, Vermillion was released when I was a poor college student, and by the time I got around to picking it up, the album was already sitting in the cutout bin and The Three O’Clock had broken up. I blamed myself, of course, but I rose above the guilt and managed to enjoy the album nonetheless. When I popped open the CD booklet, I was surprised to see a newly-familiar name amongst the members of the band: Jason Falkner, who recently come on my radar because he’d since gone on to join the ranks of Jellyfish. I also did a double-take when I hit “play” and, after the brief instrumental title track, found myself listening to a song that I already knew: “Love Explosion,” which had been written by Ian Broudie – who produced Ever After, by the way – and recorded for the first Lightning Seeds album, Cloudcuckooland. (If you haven’t already, be sure to check out Jon Cummings’ piece about that record.)

It probably won’t surprise those who only know The Three O’Clock because of the label on which Vermillion was released – Paisley Park – that my instant favorite on the album was “Neon Telephone,” written by Joey Coco…or, as he’s more commonly known, Prince…but I quickly found myself falling in love with other songs, including “When She Becomes My Girl,” “Time’s Going Slower (which comes closer to the band’s old-school sound than any other track), and “On Paper.”

That admission, of course, reveals that, yes, Vermillion is a different-sounding Three O’Clock album. It sparkles in a way that only a record made in 1988 can, with a slickness that reveals just how far the band’s sound had come since the Baroque Hoedown EP…something which many, including the newest member of the band, weren’t entirely thrilled about.

First off, how did Jason Falkner come to join the ranks of the band?

Mike Mariano (keyboards): After our original guitarist, Louis, left in 1985 we went through several guitarists. A friend said we had a ”revolving door for guitar players.” We were basically a 3-piece before recording Vermillion, and one day Danny decided he would find the right person. So he placed an ad and interviewed a lot of people. Jason responded to the ad thinking it was a band influenced by the Three O’Clock. He didn’t realize it actually was the Three O’Clock.

Danny Benair (drums): I held one-on-one auditions. We hit it off right away. We auditioned two people. For one moment we considered becoming a five piece, but Jason got the gig.

Michael Quercio (bass, lead vocals): He wowed us right away.

Jason Falkner (guitar): Let me start by exclaiming that I was a huge fan of the Three O’Clock in high school. I saw them two or three times before I was 18, and my teenage band even covered “With Cantaloupe Girlfriend” and “I Go Wild.” So, anyway, I ended up in The Three O’Clock at the ripe age of 19! I had just returned home from Alaska, where I worked in a cannery for a few months (Arrgh! That was insane!), and when I got back I placed an ad in an LA classifieds magazine called The Recycler looking for like minded people to start the best band in the world with me! I bought the issue with my ad in it just to make sure they printed my info correctly, and when I browsed down the page a bit, I saw an ad saying “Three O’Clock looking for guitarist. No metal, no country, no flakes.” I was baffled that this band that I loved and covered in high school was advertising in the same rag as I was, so I immediately called the number…which ended up being Danny Benair’s home! We talked for hours that very first call and, after they auditioned a huge number of people, I was hired.

Where was The Three O’Clock’s mindset was when the band embarked upon Vermillion? The band had worked their way up through the indie label ranks and made it to a Warner subsidiary. Were they actively looking for a hit, or were they just continuing to do what they’d always been doing and just hoping that more ears would now be able to hear and appreciate it?

DB: I think the record we wanted to make was far from Vermillion. We compromised a lot. We always wanted to have a hit.

MM: Even back in our early days, we were always trying to record hits! The bands that influenced us (Beatles, Byrds, Zombies, etc.) had hits…and we wanted em, too!

MQ: I feel on my part that I was trying to write a batch of songs to make a huge record company happy rather than myself.

JF: I was thrilled when I joined – this was going to be the beginning of everything! — but it was really hard for me making Vermillion because I felt that the group had lost or abandoned their original spirit. I mean, the Salvation Army (Michael Querico’s prior band) sounded to me like early Black Flag filtered through The Zombies. Great stuff! All the Three O’Clock records prior to Vermillion were beautiful and slightly experimental yet still ballsy, so when we started working on Vermillion, I was pretty disappointed to find all those elements traded in for really crap (1988) ”modern” production. I remember complaining to the guys that the record sounded like The Escape Club. (Look em up, kids…or not.) Where was the Syd Barrett / Beatles / Monkees thing? I was the new kid, so my opinion didn’t really matter to them. Of course, I understand that reality in a band, but I wished at the time someone would listen to me.

How did the band find its way onto Paisley Park?

DB: Prince was aware of us from Arrive without Traveling and the ”Her Head’s Revolving” video. The Bangles told us he was a fan, and when we were off IRS, he sent a label person to see us live.

MM: We contacted him and his management, asking if he was interested in having us on his label, and he said, ”Yes.”

JF: I think Susanna Hoffs had told the Purple One to sign them when he asked her what else was happening in LA, but they had already signed with Paisley Park before I joined The Three O’Clock. We were an odd choice for Paisley Park, as evidenced on our Prince-funded flight to Minneapolis to see the Love Sexy show. Every act signed to PP was on this flight, including George Clinton, Chaka Kahn, Wendy and Lisa, etcetera. We were slightly out of place! (Laughs)

How did Ian Ritchie land in the production chair?

DB: His name appeared on our A&R man’s list.

MM: We met with a few different producers, and Michael was impressed with things Ian had done, like Pete Wylie’s Sinful.

Ian Ritchie (producer): The common thread (with the artists I produced in the 80s) is that they all wanted production and arrangement input from someone comfortable with the what-was-then-very-new computer sampling and programming techniques. There weren’t many of us in the mid- to late 80s. You will definitely hear a sonic and stylistic link running through all the recordings, which is to do with how I liked to make records at the time. The band was great to work with. The recording experience was about creativity and having fun. We all liked the way the songs were developing in the studio and of course hoped that this might translate into a big selling record. We were focused on making a good album rather than being obsessed with making ”hits.”

MQ: We met with him and he was a nice guy and had done some great stuff. We were just not the band to do a super-produced 80’s album like the ones he did before. I don’t think he was into working with a not-so-super-slick rock band.

MM: Ian moved us into using a lot more sequencing than we had in the past, tipping the balance fairly heavily in that direction. If we had done a follow-up record, I think we would have moved the balance back to a more even blend of sequencing and 4 guys pounding away on their instruments.

JF: I always give people chances, and I liked Ian at first but grew to really dislike the way he worked. Bear in mind that this was my first recording experience in a REAL studio (I had been rocking the 4-track for years, but this was very different), so I didn’t really understand that you could argue your point! I think Ian choked the life out of this great band. Danny didn’t even play drums, and he was a great drummer! Shame…

DB: We settled for him, and we hated working with him. He ruined the record.

What was it like having a Prince song to record?

JF: To be honest, I wasn’t really into Prince at the time. I love him now, but when I was 19, I was into Roxy Music and David Bowie, so the whole experience was a bit square-peg / round-hole for me.

MM: Prince just wanted us to go in and make a record. One of his managers sent us a demo of three songs Prince had written, and we thought we’d take a crack at one of them.

DB: Prince first sent some funk tracks and then five others. We almost recorded a song called “Teacher Teacher” but changed our minds.

Was he ever in the studio at any point?

MM: No, he didn’t make it into the studio with us.

DB: He sent notes on demos and recording, but he had no recording involvement.

JF: We kept getting calls when we were in the studio saying, “Prince is in a limo on his way to you guys. Please clear the studio of anyone not in the band!” He never made it down. Classic.

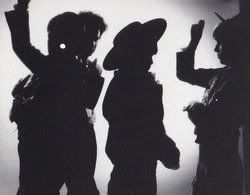

How were Wendy and Lisa to work with?

IR: We had Wendy and Lisa down to do backing vocals on (“Neon Telephone”), which was fun, although I seem to remember that we almost had a few Bangles instead!

MM: I was working on some other things when they were recording their vocals, but Danny spent time with them and had fun hanging out with them, shootin’ the breeze, etcetera.

DB: Wendy and Lisa were great. They knew how to get their sound in 10 seconds.

MQ: Great singers, and very together. They did their vocal parts in two takes.

JF: Wendy and Lisa were bad-ass! The funniest thing with that was at the end of ”Neon Telephone.” You can barely make out a mock telephone conversation between Wendy and myself. She was totally pro and sexy, saying, ”Hey, baby, how you been?” and all that kind of stuff. I, on the other hand, was shitting myself, so when you hear me, I’m, like, “Uh, I’m fine, how are you?” (Laughs) Super awkward!

Lisa Coleman (the one in Wendy & Lisa who isn’t Wendy): First, what i remember about the song itself was that Prince had a hard time finding just the right home for it, (going) from artist to artist in his own ”camp” – always female – to other bands, so I thought it was funny that then it ended up being done by The Three O’ Clock, who were all boys! Wendy and I were a little leery of doing the session because we didn’t want to be thought of as a purple sound machine, if you know what i mean, but they were persistent, and we really didn’t want anybody else singing a part that would only end up being an imitation of what we had been doing for years, so we said “yes” and went to the session. I remember the guys all being so nice and talented and cute. Doing the vocals only took a few minutes. We almost felt guilty that it was so easy! Wendy and I had been singing together and doing background vocals in that style so much that we had it down to a science. We only sang those words a few times, and we knew the harmonies already. It was easy…but they were so excited about it! I think it was like hearing something out of context, like something you’re only used to coming out of your radio, and then you hear it right in front of you! They were so funny and playful. I remember fooling around with some sexy talking at the end of the song. To us it was tongue in cheek, but to the guys it was probably like “Weird Science,” when Kelly LeBrock comes to life and it’s a little more than they bargained for. (Laughs) They were really so sweet. I was sorry to lose contact with them.

The vocals on the record were spread around, with Mike Mariano taking lead on “When She Becomes My Girl” and Jason Falkner fronting for “Love Has No Heart.” Any recollections about those spotlights? Was it something those guys had to fight for, or was it planned out well before hitting the studio?

IR: There was more than one really good lead vocalist in the band, so naturally I tried to make use of that. I seem to remember trying vocals from Michael, Mike, and Jason on a few tracks and choosing the best ones to go on the record. There may also have been a link with the writer of those particular songs, as in John singing John songs and Paul singing Paul songs on Beatles albums.

MM: I had sung on a rehearsal demo we had done of ”When She Becomes My Girl,” and Jason gave ”Love Has No Heart” a try while we were in the studio. They seemed good, so we kept them that way. Michael shouldered a lot — lead vocals, bass, all the lyrics, the majority of the music — so I think he welcomed a little break now and then, as long as the results felt good to him.

JF: I had written a song that I sheepishly played for the guys in rehearsal. Michael seemed to like it, so we learned it and he was going to sing it. Well, the song never got recorded on Vermillion, but instead he and Ian decided I should sing “Love Has No Heart,” which was written by Michael. They told me I was doing this, and by the end of that day I had sung it. Not my song and definitely not one of my fave moments, but nonetheless my first vocals on a record.

MQ: I was burnt out on being the lead singer. I wrote those songs for those guys to sing. It was a weird time in my young life. Inside I knew that this would be our final record together.

What are your thoughts on the record when you look back on Vermillion? Do you have a favorite song, or, on the flip side, a track that you still hate to listen to because you know it could’ve been so much better?

MQ: The whole thing is a big drag to me. It was not The Three O’clock in my opinion. But I do like “When She Becomes My Girl”

MM: I like ”When She Becomes My Girl,” ”To Be Where You Are,” ”Love Has No Heart,” “Through the Sleepy Town.” I don’t hate any tracks, but I think every record you make contains a track or two you felt could’ve been better…but hopefully not too many!

JF: When I think about Vermillion, I think, ”I’m really proud I was in this band, but, dammit, I wish I had been on something earlier with that wonderful spark they had!”

IR: In 1988, I was very happy with the album. Listening to it now, I hear a record that was very much of its time and has a freshness and directness I still like.

DB: I loved our engineer, Chris Sheldon, but the record was not fun to make, other than a few moments. “To Be Where You Are” was fun — we all got to beat percussion — but Ian was out to make his own record, so it’s a sad record for me.

Chris Sheldon (engineer): I was asked by Ian Ritchie to come to California to engineer his production, and my remembrance of the making of Vermillion was essentially a good one and I had a lot of fun, but in hindsight – which is always 20:20, of course – I think Ian was the wrong producer for the band. That’s not to say that Ian’s production wasn’t great as far as the emerging electronic production techniques of the 1980’s are concerned, but I don’t think it should have dominated the production and sound of what was essentially, as I recall, a relatively psychedelic alternative band to the extent that it did. I think that the two techniques should have worked side by side, i.e. the real played drums, bass and guitars of the band, who were all great players, along side the sequenced keyboards and various bits of sampling that Ian introduced, amongst other things. Of course, I wasn’t privy to any meetings that Ian may have had with the group prior to the making of the album and so don’t know what their expectations were, but it seems to me that Ian’s concept of how the record should be made and the band’s idea, was not fully discussed, leading to later frustrations that should have been dealt with at a much earlier stage. But, on the plus side, thanks to Ian, who gave me a lot of work during the 1980’s, I got to meet Danny, Jason, Mike and Michael, and I had a great time working with them.

If Vermillion had been more of a success, do you think the band would have kept going, or had The Three O’Clock simply run its course by then?

JF: That’s really hard to say.

MQ: I would hope that the follow up record would have been us going back to our roots. Danny, Mickey, and Jason were super musicians, and it would have been great to do another record with them.

MM: I would have continued, sure, and I think the other guys would have been up for it. We enjoyed recording and playing shows, and if the record had given us more inertia to keep it going, we probably would have continued.

DB: The failure made it easy to split up.

JF: In a way, I think Vermillion itself is what cracked the band. I do have fond memories of Michael, Danny and Micky, but when you listen to the difference between that record and all of their output before that, one can’t help but wonder what happened. To me, Vermillion sounds like they were trying to cash in and have hits, which hardly ever works, especially if you had been a good “real” band before. It just sounds fishy.

Comments