I sometimes think that the exaggerated esteem afforded Jack Kirby‘s body of work ultimately does him no favors. Kirby, of course, was a gaddam genius — creating (or co-creating, depending on how much credence you feel like granting Stan Lee on any given day) most of Marvel Comics’ most iconic characters, defining the visual vocabulary of graphic storytelling, and mastering just about every conceivable genre within comics, including a few that he invented himself. But there’s a tendency among Kirby fans to treat every dot, every scribble, as a legacy for the ages.

This view of Kirby, as the lone Promethean wizard creating worlds from whole cloth, began even in his lifetime — encouraged, no doubt, by the man’s unprecedented creative control over his latter-day projects. Rather than the assembly-line system of most comics, where the different jobs of putting a book together were coordinated from the central location of the publisher, Jack Kirby’s 1970s Marvel work found Kirby himself wearing all the hats. He was both writer and penciler; inks and lettering were both done by assistants (usually Mike Royer), in Kirby’s own studio and under his supervision — making him his own editor, in title and in practice. In the letter-to-the-editor pages reproduced in the Devil Dinosaur Omnibus — the first reprinting of the comic’s original nine-issue run from 1978 — the address given for correspondence is a PO box in Kirby’s California hometown, rather than, as in Marvel’s other books, the publisher’s New York City offices.

Think about that: Kirby didn’t even trust Marvel to forward his mail. That’s the level of sovereignty that he, alone of all comics creators, was afforded. No wonder they called him “The King.”

But to see Kirby as an untrammeled motor of imagination, answering only to his muse, is to miss his understanding of himself as a pop artist — and his engagement with the mass media landscape of his times. Kirby’s editorial autonomy came at a price: an ironclad obligation to deliver a staggering fifteen completed pages each week — twice what most of today’s artists can manage. Kirby was a populist by nature, always chasing a hit; and to fill all those pages, he took his inspiration wherever he could find it — especially from movies and TV programs — creating works that were ultimately of their time.

Now, some Kirby fans choose to downplay this aspect of his creative process. Oh, if pressed they’ll concede that the talking animals of Kamandi owe a stylistic debt to Planet of the Apes, but they prefer not to notice Kirby’s deep and consistent engagement with the world of popular entertainment, opting instead for the myth of the Artist in splendid isolation, creations leaping full-blown from his brow and onto the page.

But compare Kirby’s work with that of a contemporary who does labor in isolation — Steve Ditko. Increasingly frustrated with the vagaries of the comic book business in particular and what he perceived as a moral decline of society in general, Ditko has spent years withdrawn from mass media, from modernity itself, issuing forth from his hermitage only the occasional sociopolitical screed espousing his Objectivist worldview. Though it’s obvious that these works are of great importance to Ditko, they are so idiosyncratic, and so alienated from the mainstream, as to be nearly unreadable.

By contrast, Kirby even at his most impenetrably personal is recognizably steeped in pulp sci-fi, Republic serials, Icelandic sagas, Fortean weird science, the Dead End Kids — steeped in all the culture, high and low, of his lifetime. Sometimes he responded to it directly. In the mid-1970s, shortly after his return to Marvel, Kirby started work on an adaptation of the cult TV series The Prisoner.

That project never saw print; but he did complete an adaptation of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and then crafted an original series that extended its themes. Kirby’s verbose narration and the explosiveness of his artwork make for an odd fit with these projects, especially in contrast with the cool silences of the Kubrick film — but they serve to show Kirby’s engagement with the media scene around him. Elsewhere, it’s easy to see elements of then-popular films like Westworld and Logan’s Run in Kirby’s OMAC; Erich Von DÁ¤niken’s pseudo-scientific blockbuster Chariots of the Gods? was the avowed inspiration for The Eternals; the 1970s run on Captain America bore the fingerprints of Kafka, Borges, and The Boys From Brazil. And so on.

Now, I love this stuff. Not because I enjoy playing “spot the reference” (okay, not just because of that), but because Kirby is on my turf here. Absorbing and synthesizing all this pop culture material, processing it through his own filters and sensibilities, and crafting a dynamic response, affirmation or rebuttal or both — Kirby was, like me, a critic, and his work was his diary of his reading and viewing habits, translated into vibrant, imaginative stories. It’s not ephemera, exactly, but there’s a bracing immediacy to the 1970s Marvel Kirby — due in part, no doubt, to the punishing schedule under which it was produced. Kirby had always delved freely into the absurd, but his presentation had usually been more solemn; but this work is loose and playful, disposable even, in a way that the Fourth World saga never could be. And, perhaps predictably, some fans took the new whimsy as a sign that the King had lost the plot.

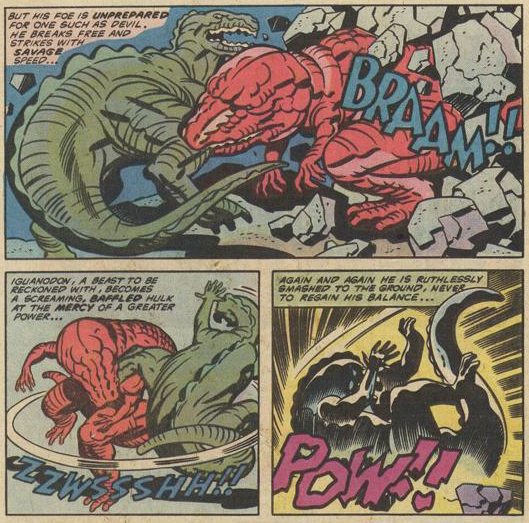

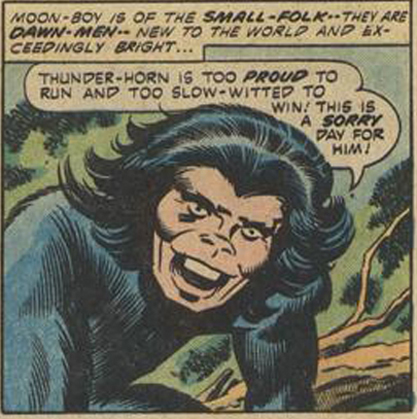

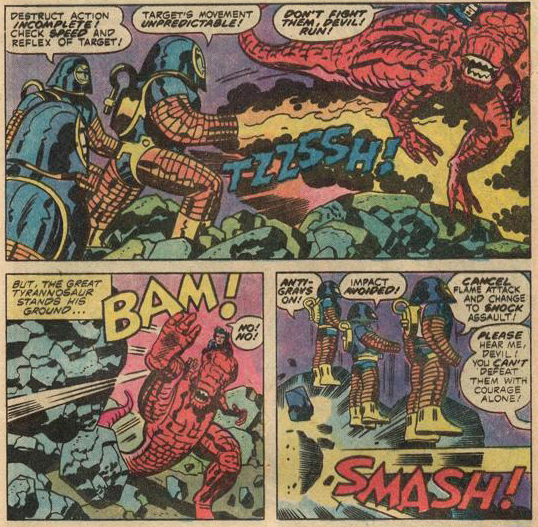

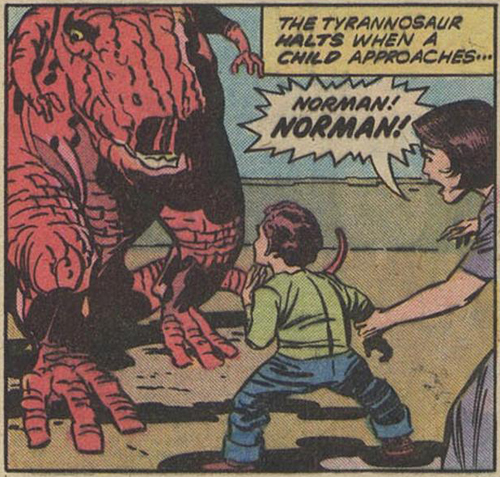

Devil Dinosaur was particularly divisive. Set in a counterfactual world where saurians coexisted with furry proto-humans, Devil Dinosaur took some visual cues from 2001‘s “Dawn of Man” sequence and much of its atmosphere from TV’s Land of the Lost. Kirby whipped up the premise with one eye on an animation deal, and indeed, there’s a distinct Saturday morning vibe to the proceedings. The title character was an unusually intelligent T. rex, his pigmentation gone bright red after being scorched by lava; he is rescued and befriended by a little monkey-fella called Moon-Boy, and together THEY FIGHT CRIME! Well, pretty much. They defend their peaceful “Valley of Flame” from aggressive ape-men, rogue predators, Agnes Moorehead-style giants, and invading space aliens.

Does that sound promising to you? Yeah, me neither. Devil Dinosaur was Marvel’s worst-selling book of 1978 — and for the thirty years since that inauspicious debut, it’s been a punchline and a punching bag for comics fans. It’s a perennial favorite in fan polls of titles they’d like to see revived, seemingly for the express purpose of letting new generations of writers and artists piss all over it. In their few appearances since the original series, the prehistoric duo have been used for comedic effect. Devil and Moon-Boy popped up in the misfit-hero book Fallen Angels, mostly to emphasize by their very presence what a pack of losers the Angels were. In Warren Ellis’s superhero satire Nextwave, Devil is revealed as the power behind a deadly conspiracy, seeking vengeance on humanity for his humiliation at Moon-Boy’s furry hands.

Devil Dinosaur, in short, has been mocked as the epitome of all that is goofy and shameful about comics, branded with the “so bad it’s good” tag. Surely this work can only be enjoyed through a heavy protective filter of irony. But you know what? It’s a really fun comic.

More than anything, it’s a sweet book. Kirby’s beating heart was never far from the surface of his work, but he was rarely as lyrical as in Devil Dinosaur. Perhaps because he was writing for a younger audience, there’s an unguarded quality to the work. The savage, untamed settings serve, paradoxically, to bring out Kirby’s gentle side. Moon-Boy, curious and kind-natured, makes a perfect viewpoint character; through his eyes, we see a world that is literally fresh and newly-made, and Kirby brings home that childlike wonder page after page.

And if Kirby — sixty years old and contracted to a back-breaking production schedule — was no longer producing work with the elegance or intricacy of his classic Thor storylines, the relative rawness, the surface crudity, just feels right. The jumbled, unformed landscapes of the morning of the world, and the great beasts locked in the eternal struggle to survive, are bold and energetic in their rendering.

The dialogue and captions are typically florid, but again, here Kirby’s stylistic tics suit the story. The weirdly stilted language is supposed to sound archaic. Devil cannot speak, so Moon-Boy — who considers Devil his “brother” — is the mouthpiece for both of them, finding time amid the frantic dinosaur battles and volcanic eruptions to deliver little homilies about friendship and loyalty, about the spirit of brotherhood that can cross even the line between species. It’s perfect kiddie fare, in other words.

Maybe Devil Dinosaur wasn’t built to last — Kirby never had it in him to spin out a single premise for 250 issues. Amid the dinosaur fights and the ancient-astronaut guff there’s a multi-issue story that amounts to an extended Gnostic parable; a time-travel story in the final issue, sending Devil to the wilds of 1978, indicates that Kirby was already restless within the confines of the Valley of Flame. But, you know, childhood doesn’t last forever, either. Give this book to a child — or, if you can manage it, strip off the armor of irony and be a child yourself for an hour or two.

Comments