I’m a big believer in simplicity where simplicity is called for. As cosmopolitan adult audiences, we’re supposed to sneer at simple stories in favor of works that are more conceptually intricate and morally engaged. We are all postmodernists now, for good or ill, and we have no patience for “kids’ stuff.” Indeed, even children’s cartoons have a self-aware, metafictive absurdity. Not for us gooey love stories or unironic boy’s-own adventures. We want subtext. We want resonance. We want complexity.

The problem is that conceptually intricate, morally engaged works are hard to come by. They always have been, of course; but that was okay, because they were a niche product, fodder for PBS and the Ecco Press. But as audiences grow more sophisticated — or perhaps simply more jaded — the perceived demand for such works is higher than ever. The mainstream has responded as it always does; by co-opting the surface elements of the avant garde — by bolting labyrinthine plot structures onto what are, at heart, very simple stories: A skeptic and a believer must work together to uncover the truth behind seemingly paranormal events; survivors of a plane crash find themselves in an environment where normal laws of time and physics seem to no longer apply; individuals with newly acquired superhuman powers encounter forces conspiring to exploit or destroy them. Simple stories all; the hairpin twists and plot reversals in which they are dressed serve only to make them complicated, not truly complex. And to the extent that these examples succeed or fail, they do so despite the convoluted storytelling, and because of their strong, simple hooks — and not the other way around.

Which brings us, by roundabout ways, to Turok, Son of Stone.

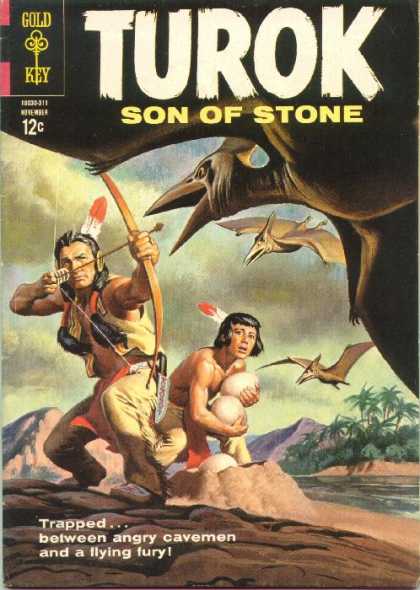

Turok made his comic book debut in 1954. A Native American hunter, Turok and his young nephew Andar stumble upon a hidden valley where prehistoric creatures still dwell. It’s a simple premise — aggressively simple, even: Indians fighting dinosaurs. Throughout its run, the series rung only minute variations on its basic formula. Turok and Andar would occasionally run into trouble with cavemen, or erupting volcanoes, or sabretooth tigers and whatnot. But for the most part, it was Indians killing dinosaurs, issue after issue. No overarching plot, no character development as such, no evolution in the status quo — not even any real attempt for Turok and Andar to escape the valley. Just single-issue, self-contained stories about Native American braves putting the smackdown onto giant lizards. Couldn’t be simpler.

It doesn’t sound like a particularly rich vein for storytelling, does it? But here’s the thing — the original version of Turok, Son of Stone ran in the comics for twenty-eight years.

Since its cancellation in 1982, the property has been revived periodically in comic books and a series of best-selling videogames from Acclaim Entertainment. The revivals have all deviated to some extent from the original premise, all in the name of “keeping the property fresh and relevant” — read, “sanding off all the edges that made the character so gloriously odd in the first place.” Turok went from an individual name to being a dynastic title, like The Phantom, or President Bush; poisoned arrows gave way to a variety of heavy weaponry.

The nadir came with the character being shoehorned into Valiant Comics‘ stable of bog-standard 90s-style superheroes, outfitted with a “cyber-bow” and pitted against bionic dinosaurs in the obligatory company-wide crossover event. Yes, I said bionic dinosaurs.

The direct-to-DVD animated movie Turok, Son of Stone constitutes a “reboot” of the franchise, taking it back to basics ” — well, sort of. The dino-borgs are gone, and Turok is a 19th-Century man again, not packing any weaponry more advanced than a tomahawk; but the movie largely fails to capture the gonzo magic of the comics. Perhaps the following little compare-and-contrast will demonstrate why this is so.

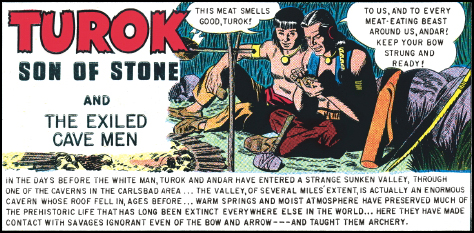

The backstory for the original Turok comics can be summed up in a single narrative caption…

Got it? Okay. Now cue 125 issues of Indians fighting dinosaurs.

The backstory for the animated film, by contrast, goes a little something like this: Teenaged brothers Nashoba and Turok are both in love with the beautiful Catori, and one day, the three of them encounter some rival tribesmen, who provoke Turok, who in turn loses his temper, kills them, and then, blood-drunk, wounds his brother Nashoba and nearly kills him, causing the elders to exile Turok even though Nashoba not only recovers, but becomes chief and marries Catori, who bears him a son, Andar, and so sixteen years pass and then the rival tribe threatens war, so Nashoba sends Andar to persuade Turok to return and fight for his tribe, but Turok refuses, clearing the way for the raiders, who are armed with guns and led by the villainous Chichak, to attack Nashoba’s village and make off with Catori, meaning Turok and Andar must ride off in pursuit of Chichak, and they all take a wrong turn, ending up in a Lost Land of dinosaurs and cave people, where Catori escapes from Chichak, and she, Turok, and Andar fall in with a tribe of civilized cliff-dwellers, while Chichak uses his superior weaponry to set himself up as god-king of some primitive beast-men, and plots the destruction of the cliff-dwellers, all while Turok must confront his own violent nature and deal with growing attraction to Catori before he can settle into his new surrogate family and meanwhile WE ARE FORTY-FIVE MINUTES INTO THIS MOVIE AND NOBODY IS FIGHTING ANY GODDAM DINOSAURS. And the movie is only seventy minutes long.

Do you see a problem here?

It’s the same problem that plagues most recent Hollywood adaptations of beloved childhood stories; there’s a fundamental lack of faith in the source material. Did any kid ever read Dr. Seuss’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas and say, “You know what this book needs? An extended backstory explaining how the Grinch became such a misanthrope — maybe a flashback to some childhood trauma that caused him to turn his back on Who-ville”? Did any child ever come away from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory craving an exploration of Willy’s relationship with his father?

Hell, no. Only an adult could be that stupid, an adult with the bottomless self-loathing of the fanboy writer. He loudly proclaims his love for the stories of his childhood, but at bottom he is embarrassed by them — because as an adult he recognizes that they’re actually kind of dumb and goofy, and he fears that loving them means that he is dumb and goofy. And so he reshapes the tales of his youth into something fit for the adult that he aspires to be: slick and hard and ironic. And they are made devoid of mystery, because the fanboy writer hates unanswered questions, which might force him to admit that there’s something he does not know. The revamped version is always at pains to explain everything — to answer all the questions that the fanboy’s child-self wouldn’t bother to ask — so that there can be no doubt as to the fanboy writer’s cleverness.

But it’s the child who’s the wiser here. A child doesn’t bother to ask why the Grinch is as he is because he knows, instinctively, that it’s not a question worth asking; a child understands, without spelling it out, that the Grinch is an archetype, a force of nature. You don’t enquire as to the motivation of a hurricane; you don’t explore the backstory of a tidal wave. It simply is what it is, and it neither requires nor rewards explanation. The same can be said, I think, for the primal majesty of Indians fighting dinosaurs.

(Adaptations of this type also tend to be glossed up with sex and violence — because there’s nothing more adult than sex and violence, or so the fanboy writer imagines. There’s no sex in Turok, Son of Stone —though Andar is provided with a hawtt cliff-dweller girlfriend in a cleavage-baring buckskin camisole — but man oh man is it violent. Severed limbs and heads fly willy-nilly, with an abandon not seen since 300.

Spears poke through chests; people get shot through the head at point-blank range, or torn in half by savage beasts; blood splashes by the bucketful. In one scene, a cannibal caveman munches happily on the corpse of his murdered chief; yum. The DVD is unrated, but if this were live-action it would be a hard R.)

[kml_flashembed movie="http://www.youtube.com/v/qLp9bEKsIBg" width="425" height="350" wmode="transparent" /]

It would be one thing if all the gore and the overstuffed plot actually brought anything interesting to the property, but it all feels pretty threadbare. In the end, the limitations of the original premise start to look instead like a conceptual purity. The makers of this movie have lavished considerable care on the production — the character designs are gorgeous, the musical score terrific, the animation fluid and at times quite beautiful — but they’ve given all their attention to the individual trees, without noticing that they never quite add up to a forest.

The making-of featurette on the DVD spells this all out in dumbfounding detail. The voice cast, we learn, is a Who’s Who of Native American actors working in Hollywood — Adam Beach (Flags of Our Fathers) takes the title role, with supporting work from Irene Bedard (Disney’s Pocahontas), Michael Horse (Twin Peaks), Graham Greene (Dances With Wolves), and Russell Means (Natural Born Killers), among others. That makes sense, I guess, because if there’s one thing that a cartoon about Indians fighting dinosaurs needs, it’s an A-list voice cast, right? And the costumes and weaponry have been painstakingly researched, because if there’s one thing that a cartoon about Indians fighting dinosaurs needs, it’s historically-accurate weaponry. All the depictions of Native American culture have been vetted by a team of tribal representatives, because if there’s one thing that a cartoon about Indians fighting dinosaurs needs, it’s culturally-sensitive portrayals of native folkways, right? Right?

Wrong. If there’s one thing that a cartoon about Indians fighting dinosaurs needs, it’s SOME INDIANS FIGHTING SOME MOTHERFUCKING DINOSAURS. QED. Lacking that, the film can’t help seem hollow. For all its meticulously-paced character beats and buckets of blood, it comes off as an ornate, gilded rococo frame placed ’round an empty canvas. It fails as an adaptation, and the you-dirty-rat-you-killed-my-brother plot is too tired and generic to be interesting on its own. Turok, Son of Stone is undoubtedly well-made, but there’s a hole at its heart. An Indians-fighting-dinosaurs-shaped hole.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=3aca0367-0b65-4846-b75a-105b721d15ac)

Comments