We are excited to introduce a new column to the site! Most everything we write about on Popdose — music, film, books, tv and other cultural diversions — consists of one or more forms of intellectual property. Keep It To Yourself will look at how that valuable media is owned and controlled, used and abused, both legally and illegally. The column is a project of Jonny Balfus, an intellectual property lawyer as wells as a longtime friend and occasional contributor to Popdose. Know Your Rights’, as the man once said, and enjoy this new perspective on the content we consume.

Here we go with the first installment:

Okay, so a couple of weeks ago snobby British fashion house Burberry posts a timeline on Facebook including a shot of screen legend Humphrey Bogart, like so:

And then everyone started suing each other! You know daddy likes it when that happens!

The mug is from the 1942 Oscar-winning flick Casablanca. The timeline features other expired celebs like Robert Mitchum, Tyrone Power, George C. Scott, Audrey Hepburn, and personal fave A-Team top dog George Peppard. There’s also a still of a Burberry-clad Meryl Streep from the 1979 flick Kramer vs. Kramer — but she doesn’t figure into this post because she’s not dead.

Right, so Bogart’s estate sued Burberry in California asserting violations of the actor’s right of publicity, trademark and other common law rights. Then Burberry sued the actor’s estate in New York, asserting that it has First Amendment rights to recount its history and may permissibly show that Bogie and other dead stars wore its admittedly fly raincoats.

So what’s gonna happen, paleface? Depends. A ”Right of Publicity” prevents the unauthorized use of someone’s unusual name, likeness, or other recognizable personal traits. It’s the exclusive right to control and license the use of one’s distinctive identity for commercial purposes. Gravel-voiced Tom Waits, for example, enjoined chip-slingin’ giant Frito-Lay, Inc. from using a sound-alike singer in an ad for their noisy snacks. And Vanna White successfully sued Samsung for running a commercial in which a robot duplicated her unique Wheel of Fortune letter-turning talents, on grounds that her identity was readily identifiable from the context of the ad. (Ironic since Vanna herself is an artificial humanoid replicant fabricated by Stepford Wives, Ltd.)

Although there’s a fair bit of precedent for enforcing rights of publicity, controlling law differs all over the country. Only about half the states recognize these rights and most of those that do don’t actually refer to the ”right of publicity” as such, but rather a category of the Right of Privacy. Modern tort law recognizes four types of Invasions of Privacy: (1) intrusion, (2) appropriation of name or likeness, (3) unreasonable publicity, and (4) false light; the depiction of someone in an unflattering or misleading context.

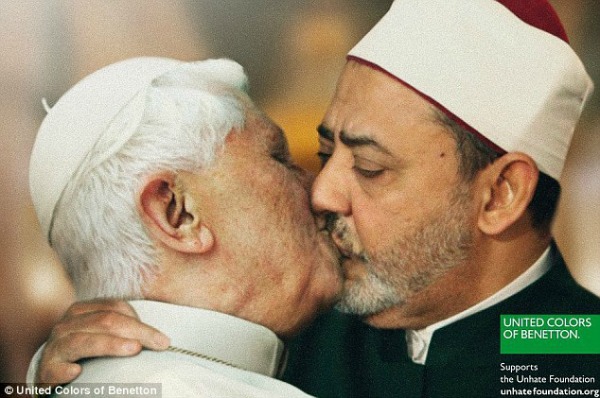

The “false light” theory was recently invoked when the Vatican sued Benetton for an ad using the image of the Pope kissing an imam. (Yes, that Vatican — Pope Benedict XVI blessed a settlement last November.) In some states, violation of the right of publicity is also grounds for a claim for unfair competition. And, if a person can establish that an aspect of his or her identity is recognizable as a trademark, protection against its unauthorized use to falsely advertise a product may be asserted under the Federal Lanham Act.

Bogart’s estate sued in California where the Celebrities Rights Act is in effect. That statute, which extends the personality rights for a celebrity to 70 years after his or her death, was enacted in 1985 in response to the California Supreme Court’s 1979 decision in Lugosi v. Universal Pictures. The high court decided that Bela Lugosi’s creepy personality rights could not pass to his heirs like other forms of intellectual property, such as a copyright. It ruled that any rights of publicity, and rights to his image, terminated with Lugosi’s death. (Totally unfair since, by definition, vampires are the living dead.)

Now the California Civil Code also has a section familiarly known as the ”Astaire Celebrity Image Protection Act,” which grants statutory post-mortem rights prohibiting the unsanctioned use of the ”name, voice, signature, photograph or likeness on or in products, merchandise or goods” of any person. As you can imagine, these rights can be extremely valuable. The Associated Press reported that Michael Jackson’s estate generated $310 million from the time of his death in June 2009 through December 2010. Shamone!

By contrast, in New York, once you die you’re pretty much dead: the right of publicity is not recognized. This means your fame doesn’t survive you and your slacker kids can’t exploit it as a commodity after you’re gone. So, Burberry isn’t up against the contrary California scheme there. Stand by: the two cases will proceed along their respective routes until they inevitably crash into each other in a blaze of conflicting law and awkward precedent. Daddy likes it when that happens, too.

True Fact: Burberry’s Facebook timeline skips from 1999 to 2004. I’m guessing that the upper-crust luxury merchant wasn’t quite chuffed during the early 2000’s when its particularly posh plaid was hijacked by the UK lowlife phenomena known as the ‘Chavs’. Rather!

Comments